Bahia was once the center of the chocolate universe. A region in eastern Brazil, it is a lush tropical paradise. Lizards skitter up trees. Birds, seen and unseen, make themselves heard.

Everything changed when a fungal infection swept Bahia. The fungus, called witches'-broom, only attacks cacao trees, and it ravaged the chocolate industry in Bahia in the late 1980s and early '90s.

Its effects didn't end there, though. The first law of ecology is that everything in nature is connected to everything else, so a fungus that attacks cacao could change an entire ecosystem and way of life.

A Devastating Disease

Claudio Dessimoni owned a cacao farm on a hillside in Bahia. Once a major player in the chocolate industry, he says the farm meant the world to him. It was thick with squat cacao trees studded with brightly colored football-shaped pods — the source of chocolate. Two rivers and seven streams ran through the land. The farm was a 500-acre heirloom started by his grandfather in 1919.

Seventy years later, disaster struck.

Witches'-broom arrived in Bahia in 1989. The mold, which is carried on puffs of wind, had already caused problems in northern Brazil. Dessimoni says he doesn't know how it traveled all the way to Bahia. Some say it was deliberately brought in to destroy the chocolate industry and its rich landowners.

Whichever way it reached Bahia, it killed Dessimoni's cacao trees.

"The plants start dying," he says. "All the leaves drop. Completely brown."

The fungus is named for the growths it creates — clusters of dead leaves and stunted little branches that look like witches' brooms stuck to the trees.

Dessimoni went out with his workers, chopping off infected branches and planting new trees he thought might be resistant. But like the Sorcerer's Apprentice, he couldn't keep up. With mist in his eyes, he says the stress killed his wife.

Finally, in 2001, the government declared Dessimoni's farm nonproductive, which meant the government could seize it and give it to landless people.

"Now I am poor, but I was rich," he says.

Dessimoni was not the only one devastated by the microscopic fungus. Cocoa production across the entire region plunged nearly 75 percent. Brazil went from being the world's third-leading cocoa producer to being the 13th.

He doesn't know what has happened to his farm since the government took it from him.

"I nevermore went there," says Dessimoni. "I believe I can't see the farm anymore."

An Ecosystem Transformed

A few cacao farms survived. But by destroying so many cacao trees, witches'-broom transformed the entire ecosystem.

Before the fungus hit, the region had more than a million acres of lush rainforest. The soil was moist and absorbent and soaked up moisture during the rainy season. During the dry season, the absorbed water slowly drained into the Cachoeira River.

But with the death of the cacao trees, people cut down the forest to make money from timber and pastureland. The exposed soil was tamped down by animals' hooves and burned by the sun. In the watershed where Dessimoni's farm used to be, the ground is now hard and dry.

The shift from forest to pasture greatly altered the area's water flow, says Neylor Calasans, who works at the Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz in the city of Itabuna, on the Cachoeira River.

"As long as we change it for pasture, the water is not able to enter the soil," he says. "It just touches the soil and runs off."

Calasans has been monitoring water flow, temperature and precipitation in the watershed. His charts reveal that instead of being absorbed by the spongy soil, the water rushes straight off the hard-packed dirt and into the river, sometimes leaving no water in the ground to feed the river during the dry season.

"This is causing several problems," he says. "Itabuna, they are having problems of water supply for the city, especially during this period of the months that we receive less precipitation, from May to August."

There have been days in the city of Itabuna when the river simply does not flow.

And all because a microscopic fungus attacked a crop, made farmers lose their farms, turned lush dark forests into dried out pastureland and changed the way a river flowed.

Replanting the Forest

But Dessimoni and others are fighting back.

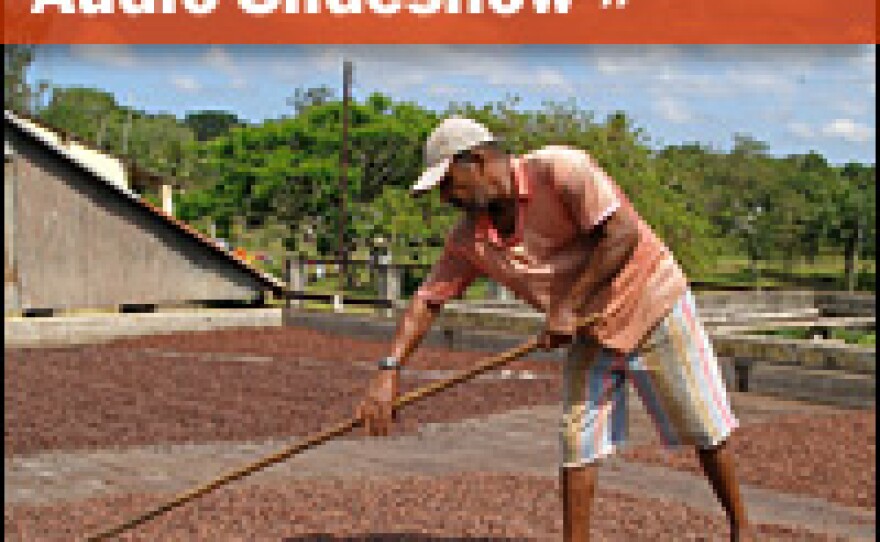

He is now a manager at a government-subsidized tree nursery. When he was a successful farmer, Dessimoni expected that by this stage in his life he would be retired and watching his daughter run the family farm. Instead, he is supplying trees to local farmers, including fruit trees and trees whose wood can be harvested sustainably.

The nursery even has some cacao trees that may be resistant to the dreaded witches'-broom.

Through planting trees, the government and people like Dessimoni hope to help the land return to a state closer to the original rainforest. Chocolate may never again thrive in Bahia, but the other trees that farmers plant will make the soil moist and spongy. Maybe water will once again flow in the river on hot, dry days.

"I didn't solve my problem," says Dessimoni. "But probably I will solve the problems of another farm."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))