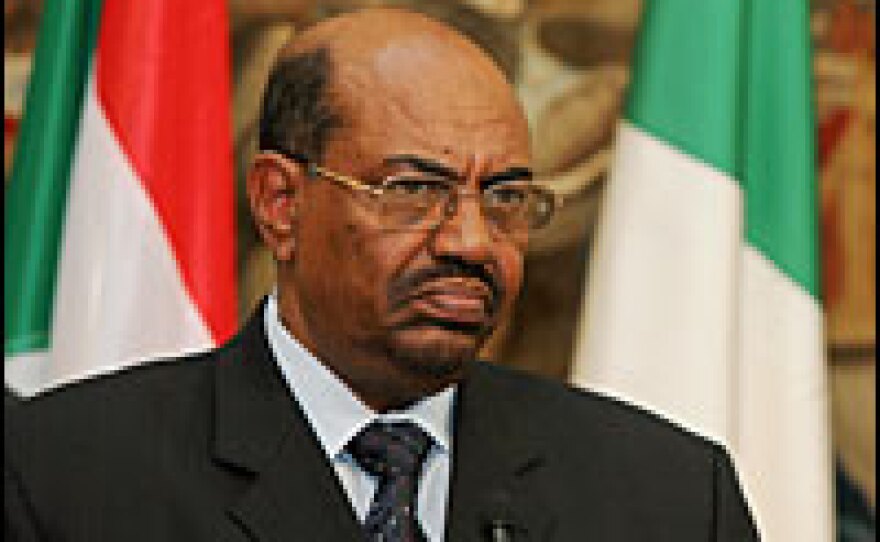

The International Criminal Court's chief prosecutor has charged Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir with genocide and crimes against humanity.

The charges announced Monday in The Hague, Netherlands, immediately stirred controversy — not so much over whether they were factually justified, as whether they would help or hurt diplomatic efforts to end the crisis in Sudan.

Bashir is accused of masterminding an effort to destroy key ethnic groups in southern Sudan and Darfur. The court's chief prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, announced the list of charges, saying Sudan's leader is also accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity, "including murder, extermination, forcible transfer of the population, torture and rape."

Moreno-Ocampo requested the court issue an arrest warrant for Bashir. The Sudanese leader's arrest could prevent retaliation against the more than 2 million people who have been forced from their homes and targeted by a government-backed militia.

John Norris of the Enough Project, an activist group, says Moreno-Ocampo is simply pointing out "the elephant in the room." Norris says it is an unacknowledged fact "that President Bashir really is the person most directly culpable for the tragedy that has been Sudan in recent years."

Some observers question the court's move, saying that while they might agree Bashir should face charges, they were unsure of the strategic value of indicting the Sudanese president at the same time the United Nations is trying to negotiate with him.

Alex de Waal of the Social Science Research Council says there would be no point in having an International Criminal Court if it could not make indictments that attempt to hold leaders like Bashir accountable. But he says the U.N. is still trying to clear the way to send more peacekeepers to Sudan and get the government involved in serious peace talks with rebel groups.

"These aims cannot be successfully pursued," de Waal says, "if there is simultaneously an attempt to arrest the head of state, an approach that criminalizes the entire governmental apparatus."

Norris dismisses such concerns, saying the situation is so dire and President Bashir has proven so intransigent in the past, that the indictments are unlikely to make matters worse.

"I think it's a little bit akin to being worried that calling a fire truck will upset the arsonist," Norris says.

In fact, Norris says, the indictments could give the U.N. Security Council more leverage to get Sudan's government to take the peace process seriously. The Security Council has the power to quash the indictments against Bashir if he changes his behavior.

Additionally, Norris says, the charges might help undermine Bashir's support if his backers think his grip on power may not be so secure.

On Monday in Sudan's capital, Khartoum, government supporters staged a small demonstration denouncing the charges against their president. But Bashir's response was comparatively low-key. In a statement aired on government TV, he merely repeated his previous stand that the International Criminal Court has no jurisdiction in his country, and said the charges of genocide were lies.

Judges in The Hague are expected to take months to study the evidence against the Sudanese president.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))