A population of 102 million people under the age of 25 is a potent force anywhere. Added to Pakistan's combustible mix, they could be a political tsunami.

The South Asian nation's younger generation is not only large -- 58 percent of the total population of more than 174 million -- but also deeply divided among itself. It's in the midst of a battle between fundamentalism and secularism, inward versus outward orientation -- the influence of which will most certainly play a significant role in Pakistan's future.

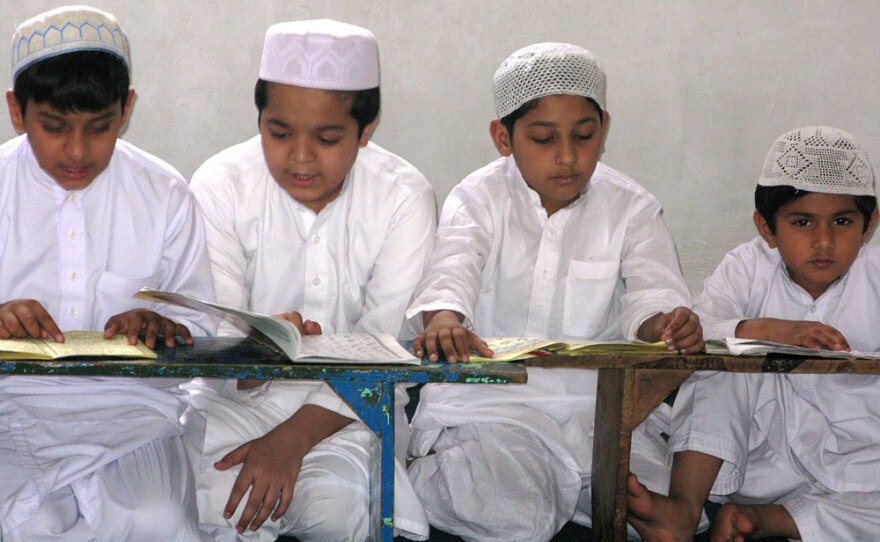

On a recent day in Lahore, one of the great cities along the fabled Grand Trunk Road through India and Pakistan, small boys in skullcaps memorize verses from the Quran. They huddle over the holy book in a madrassa, a religious school, which is as old as Pakistan itself.

Touches of Lahore's resplendent Mogul architecture are visible in the arched passageways, where students have quiet conversations. Tuition is free at the Jamia Ashrafia madrassa and the interpretation of Islam is strict.

The Madrassa Student

The total enrollment numbers at Pakistan's madrassas differ widely, depending on the source. Moeed Yusef, an analyst at the U.S. Peace Institute who has been studying Pakistani youth, says figures range from 600,000 to 2 million -- relatively small numbers in densely populated Pakistan, but significant nonetheless.

"So they are a distinct minority of students, but 1 percent of 50 million is still 500,000 radicalized people," Yusef notes.

The influential Jamia Ashrafia serves some 3,000 mostly underprivileged students. Master's student Shakeel Ahmad's background, however, is a bit different: He enjoyed a comfortable upbringing, worked in journalism and law, and ran with a career-conscious crowd.

But the secular world that had enriched him financially left him impoverished spiritually. Ahmad, 32, found fulfillment at Jamia Ashrafia studying Islam, the faith upon which Pakistan is founded.

His personal story embodies the very conflict under way in Pakistan: whether to be worldly and Western or to look inward. Ahmad is uncompromising: Pakistan, he says, must adopt a fundamentalist religious course, including Shariah, or Islamic law.

"We are all fundamentalists because we believe in one book. That is a system that we have to bring, and whenever we try to bring that, difficult times will come. And we'll do it today or we'll do it 100 years after. That is the only solution. Otherwise things are going to go as they are," he says.

Ahmad hints at an Iranian-style revolution if Pakistan's ruling elite fails to recognize the realities facing the millions of uneducated poor in the country.

Students at the madrassa think the government is corrupt and that it's propped up by the United States. American troops in neighboring Afghanistan offend their faith.

Ahmad says Western influence is poisoning Pakistani identity.

"We are giving away our own values and our own religion, and that is never good. And you try to be not yourself but somebody else. So I think that's not natural," he says.

Ahmad believes that the invasion of American fashion, music and media is also polarizing Pakistani society.

"These kids that are following the West, they will find it hard to fit in this society because this is not us. You have to look at the larger population, and you cannot let these very few people dictate terms for them," Ahmad says.

When asked whether young people who are deeply influenced by the West, who are Facebook aficionados or frequent Starbucks, risk becoming strangers in their own land, Ahmad responds: "Yes, yes they do. They are. ... The divide is there."

Citizens Of The World

In a posh part of town just a few miles but a world away from the madrassa, Rana Noman Haq sits squarely on the Western side of the divide.

"We can't live a caveman's life anymore. Things have changed, times have changed," he says. "You have to modernize yourself ... you have to move forward with your life."

Haq, 31, splurges on European vacations and eats at McDonald's.

"You can't say 'no' to a nice juicy beef burger. You can't," he says, laughing.

Sitting at a trendy cafe next to his boutique, Haq argues that his worldly lifestyle is not incompatible with Islam -- and it is not diluting his Pakistani identity.

"That's what globalization is all about -- globally, everybody is coming together. We're still sticking to our values, but within that we are also comfortable with whatever [is] happening anywhere in the world," he says.

Haq's business partner, Sehr Murtaza Latif, says the West is being made a scapegoat. She's a 25-year-old who flaunts a Gucci bag and a defiant attitude about the rising conservatism in the country.

She says she doesn't feel any connection to students at the madrassas.

"Please, I just want to kill them all," Latif says, laughing. "No way. I get so angry when I just hear that."

"Look at what they are doing. Look at our image, look at Pakistan. I mean, this is who we are, this is what we are. We are not a bunch of conservative religious fundos [fundamentalists]. We're not. No. So that's what gets me angry," Latif says.

Haq interjects: "We're a peace-loving nation, and we just want to live and let live."

Except, of course, when it comes to the fundamentalists.

"That's why I want to kill them, right? That's why I said I want to shoot them all," Latif reiterates.

Vying For The Vast Middle

And that attitude, says 33-year-old businesswoman Kiran Chaudhry, is just as bad as that of the madrassa students.

"That is fundamentalism, right back at you. Isn't it?" she says.

The Oxford-educated entrepreneur says intolerance on both sides is deepening the divide. She says religious fundamentalism is gaining ground in Pakistan because millions of people are losing ground economically.

"The fact that people are poor, that there [are] no opportunities, there are no jobs. People don't have enough to eat. What do they do? They're actually just lying around waiting to die. These are very alarming conditions. ... Any kind of rallying point that allows people to overthrow the established system is going to take off. They just want change," she says.

Chaudhry is a lawyer by training -- and a night club events promoter and singer by profession.

She currently stars in the Pakistani production of Mamma Mia!, cast in the rollicking musical as a larger-than-life unwed mother -- not your usual fare for conservative Pakistan.

But in this entertainment-starved country, Chaudhry is determined to push the boundaries. She says the deeper the divide over culture and identity grows, the more she feels the need to remain in Pakistan.

"There are going to be two poles, and this is the one that needs strengthening and that's why we're here. You can't just run. This is our country, this is our home. There has to be moderate, enlightened, self-questioning going on," she says.

But the singer -- who calls her music her "religion" -- also wonders how long before she will be assailed for being "too secular."

Yusef, the U.S. Peace Institute analyst, says the warring poles each make up a small minority in Pakistan -- especially Western-oriented youth such as Chaudhry, Haq and Latif.

It is the great mass in the middle that will determine Pakistan's future.

But Yusef says a "creeping mindset" is pushing that middle toward the "religious right" and away from anything Western or secular.

"Because ultimately secularism as a concept is abhorred by most Pakistanis. So if they have to pick a side, it's going to end up being this right-wing sort of wave that we find in Pakistan today," Yusef says. "So again, this may not be religious fanaticism, but this is a very deep-rooted sense of being culturally conservative."

Even as the modern world presses in, it is the culturally conservative and deeply religious self-image of Pakistan that may prove as enduring as the country's centuries-old Grand Trunk Road.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))