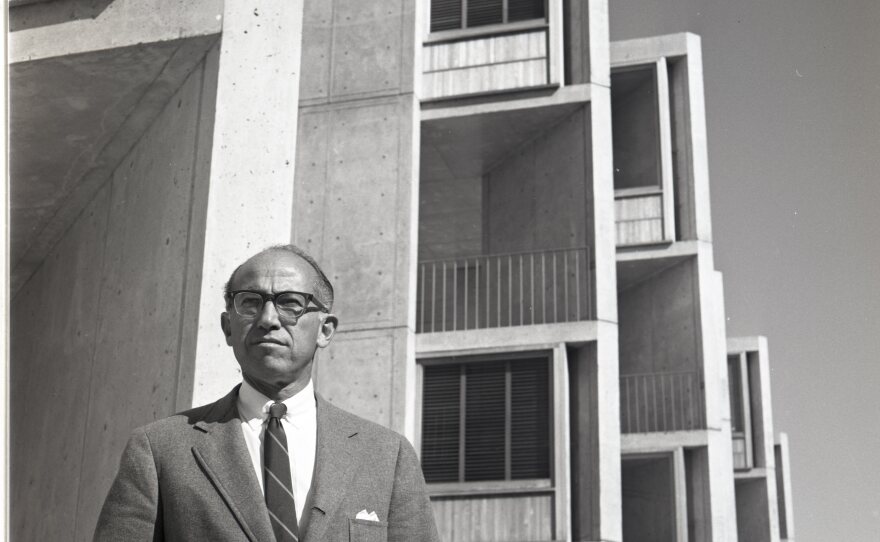

In the late 1950s, Jonas Salk, famous for creating a polio vaccine, wanted to build a research institute.

A site with a view of the Pacific Ocean was chosen in San Diego. An architect named Louis Kahn was chosen. It was clear that Salk envisioned a building that would, itself, be a work of art.

“One of the mandates that he gave to Kahn was he wanted a place that would be worthy of a visit by Pablo Picasso,” said Greg Lemke, an architecture enthusiast and a professor of neurobiology at the Salk Institute of Biological Studies.

The La Jolla-based institute is raising money for a new building now. It will be the second expansion of its campus since its founding in the early 1960s with two buildings that have become an icon of modern architecture.

The original structures are the standard against which all new buildings on the campus are judged.

The geometry and the sharp lines of the original buildings, made of poured, reinforced concrete, and their embrace of the Pacific Ocean have made the Salk Institute a National Historic Landmark that’s renowned for its beauty.

But Lemke said the features that visitors and admirers don't see were what make it a great building for science.

“The design of the buildings facilitate doing the science here,” Lemke said.

One example is the skeleton of trusses that bear the building’s weight.

“There is a series of trusses that span from these towers here to the exterior stairwells,” he said. “And what that means as a practical matter is that none of the interior walls of these laboratory spaces support any weight.”

That means walls are made out of drywall that can be broken down to reconfigure spaces, or made out of glass to let in natural light and create an open atmosphere. Jonas Salk and his architect wanted to create a collaborative space where scientists would encounter each other and observe colleagues' work.

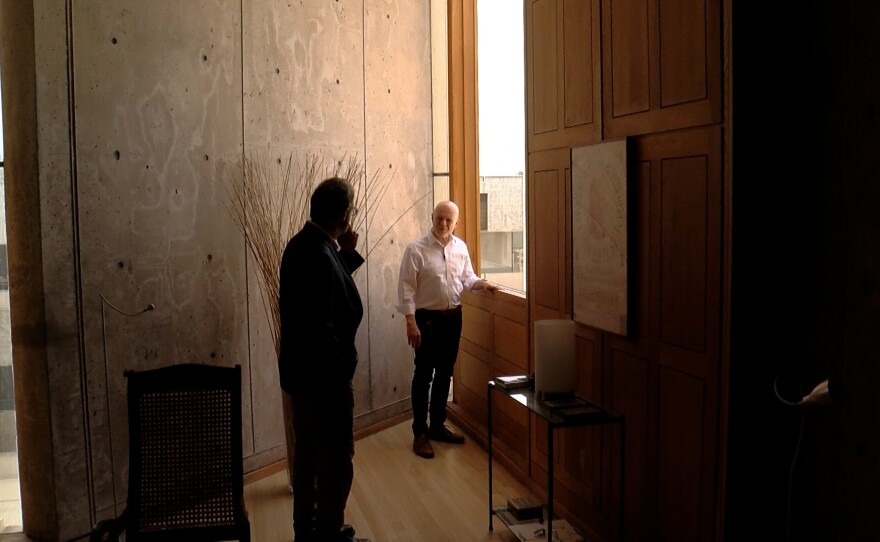

Lemke stands next to a glass door that leads to a corridor of connected labs.

“So, when you walk down this corridor, you walk from one lab to the next lab to the next lab,” he said “There are no walls between them. There are no barriers. This was a unique design feature at the time. It’s been emulated and duplicated in science labs all around the world.”

Other Salk faculty members share Lemke’s views.

“The beauty of the building is that it’s now about 60 years old, and it has continued to keep pace with our changing science,” said Sreekanth Chalasani, a neurology professor at Salk who said he had seen the building change to meet his research needs.

Chalasani needed a new room to accommodate his lab’s experiments with mice. He said he talked to the institute’s facilities guys and they created a new room. Getting the room took about two weeks.

“All they had to do was stick some metal poles from the ceiling to the floor, and stick pieces of drywall in,” Chalasani said. “That was it!”

Some problems along the way

In the early 1960’s, architects couldn’t predict the future or some of the problems that would surface in later years. One of them, Chalasani said, has been the abundant use of wireless technology. The Salk buildings’ reinforced concrete walls, for instance, do a great job of blocking cell and WiFi signals.

The institute has had to install more than a thousand WiFi access points — the round plastic discs that are attached to walls — to address the problem. Descriptions of cell coverage in the original buildings, which their provider has tried to boost, range from “pretty good” to “terrible”.

And then there are the teak shutters and panels that Louis Kahn made a key visual aspect of the building. The local environment, which includes many eucalyptus trees, caused tremendous degradation.

“A lot of the spores that come off of the sap that gets suspended in the air gets out on the wood, which then, joined with the moisture of the ocean air and whatnot, creates dry rot and surface degradation,” said Tim Ball, the director of facilities and planning at Salk.

He described the eucalyptus trees as “very acidic.”

Ball said it cost nearly $10 million to restore and, in some cases, replace the teak panels. The process was all the more difficult because Salk had to meet strict historic preservation rules as a National Historic Landmark.

Salk Institute’s future and an expanded campus

The restored teak panels and shutters frame the personal study of Salk neurobiology professor Lemke, who slides open a window with a view of the Pacific Ocean that’s shrouded this morning in a heavy mist.

Lemke said building a place like the original Salk buildings would be prohibitively expensive today, especially given the creation of interstitial floors. Those are 9-foot floors that lie between each primary floor, which provide valuable storage space and contain the guts of the building — such as the electrical wiring and gas lines.

Ball said the new building planned for the Salk campus would be built in the same style, lined up with the original plaza and its symbolic stream, called the Channel of Life.

“It’ll have an open slot roof that will allow us to take the view from the sky to the sea, being transformed from a Channel of Life, from a light and air standpoint, to the water feature in the main courtyard, which is the Channel of Life that leads to the sea of discovery,” Ball said.

The original buildings for the institute’s campus were paid for by the March of Dimes, which also funded the research that led to the polio vaccine. The Salk Institute is now raising money for the new building, which is expected to cost $250 million. Salk representatives hope to break ground on it by the end of the year.