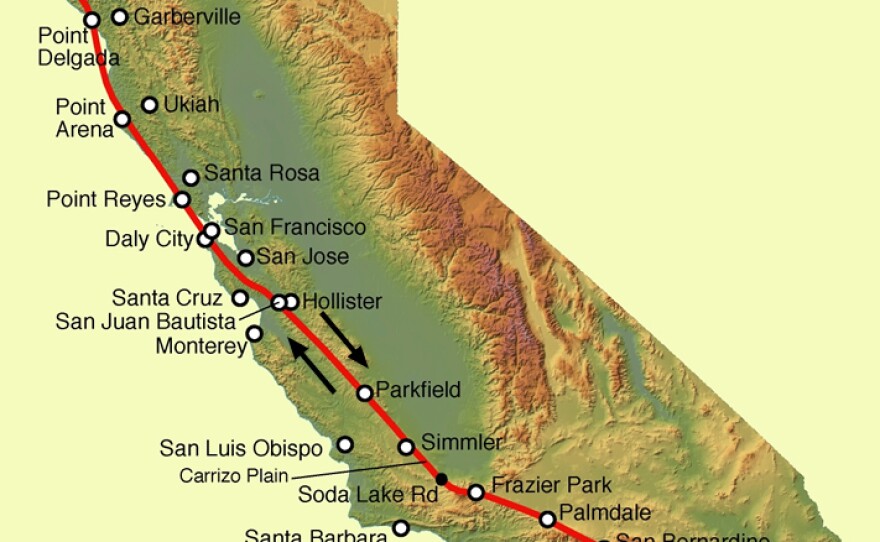

When it comes to earthquakes in Southern California, we've all been warned about "the big one." Seismologists have long been predicting that the San Andreas fault is due to create a massive quake and many say this quake is 100 years overdue. Now, a new study by researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography provides a explanation as to why the delay, suggesting lake load, or lack there of, plays a role in the timing of large earthquakes on the southern part of the San Andreas fault.

Guest

Dr. Debi Kilb, seismologist from Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Read Transcript

This is a rush transcript created by a contractor for KPBS to improve accessibility for the deaf and hard-of-hearing. Please refer to the media file as the formal record of this interview. Opinions expressed by guests during interviews reflect the guest’s individual views and do not necessarily represent those of KPBS staff, members or its sponsors.

CAVANAUGH: There are no concerns about a megaquake for Southern California. Proposed San Diego County voting districts are challenged by the ACLU. This is KPBS Midday Edition. I'm Maureen Cavanaugh. It's Tuesday, June†28th. On today's show, we'll hear about testimony before the county board of supervisors challenging how the board draws up its new voting districts. And a report on how San Diego's LGBT community has become a political force in San Diego. But we begin with earthquakes.

We've been warn forward years about the big one coming to Southern California. Seismologists have long predicted that the San Andreas fault is ready to create a massive quake. Many say this is a hundred years overdue. A new study by researchers at Scripps institution of oceanography provides an explanation as to what may be causing the delay. And it may have a lot to do with human interference. Joining me now is doctor Debbie Kilb, seismologist from Scripps institution of oceanography. Doctor Kilb, hello.

KILB: Thanks for having me on.

CAVANAUGH: What does your research indicate might be delaying a quake?

KILB: What our research shows is that the incidence of lake holding can trigger faults beneath the sea, those in turn could trigger the San Andreas fault. It's a two step sequence that our research is looking at.

CAVANAUGH: Explain lake loading for us.

KILB: When you have a very large lake, very, very large, the Salton Sea is just a mere fraction of what was there in the past, when you have the large lake, that can put an enormous amount of pressure on the bottom of the lake. That could trigger earthquake ruptures beneath the lake.

CAVANAUGH: There's a second part, and it has to do with the diversion of the Colorado river. The Colorado river water also provided a load, a geological load that seems to in the past have triggered a number of smaller earthquakes.

KILB: That's correct. But there's a little bit of misconception. I'm so glad I got the chance to talk to you today. What is happening is that the river would flood into the basin where the Salton Sea exists, and it would build a very, very large lake. This is back in 900 AD. Then that would then recede, then it would grow again, and then it

would recede and grow again and recede. That would happen 4 or 5 times over the course of the years, and that lake increase and decrease seems to correspond with large earthquakes on the sound San Andreas.

CAVANAUGH: But we don't do that anymore because we've diverted the river.

KILB: Right. We're no longer going to have that lake load. That part of the equation is completely gone. What's happening is that we've reset the clock. We would have a large earthquake on the San Andreas about a every 200†years. Earthquakes 200†years, earthquake 200†years, earthquake 200†years. Ah, but now we don't have that lake load. So we don't know what the recurrence is going to be.

CAVANAUGH: Not only the timing is different but the intensity of the quake we would see would increase? ?

KILB: We're pretty sure that we're overdue for an earthquake on the southern part of the San Andreas. That's due from plate tectonic motions. We think that will happen. It's just a matter of when. How big, it's impossible to have a magnitude nine. We don't have the large fault area to host that large of an earthquake. The large evaluate I would say we could have is about a seven and a half, 7.7.

CAVANAUGH: What would make this area of the fault spring back to life?

KILB: Earthquakes happen, it's a complicated region, and complicated to understand. You're using surface measurements to understand what's going on very deep in the earth.

CAVANAUGH: Where does this fall in the big one that we've been hearing about for so long? You seem to be saying to me that what you found out is that the lake load that we don't have anymore in the Salton Sea on a regular basis that perhaps went for millennia has been relieved by the diversion of the Colorado river water. Therefore we may see more of fault intensity when that big one on the San Andreas does arrive here in deep Southern California.

KILB: I think that's taking it a little bit too far.

CAVANAUGH: Okay.

KILB: What our study really did was say we're a hundred years overdue for an earthquake. Why? We didn't really understand why. And our study put forth this hypothesis, this domino effect of triggers of fault beneath the lake, lake triggers, the San Andreas. Now we take that out of the equation, now it says why it's 300†years, because we reset the clock. We don't know what the interval is going to be. If we reconvene in another thousand years or so, we would see what the new period is going to be. We're basically starting this now period, and we need to gather more data to find out what the recurrence is going to be.

CAVANAUGH: How do you know the San Andreas is years overdue for an earthquake?

KILB: It's a tricky business. We have had seismometers since the early nine hundreds. You could see fault off sets and try to estimate when the larger earthquakes might be. If we want to take it back before 1700 or so, we used what's called paleoseismology where you're really going in and looking at the different layers, getting some samples to get some actual dates on when the faults ruptured.

CAVANAUGH: We don't often think of surface events, lake loading or the building of a dam actually interfering with the tectonic pressures that cause earthquakes. Does that happen often? ?

KILB: It does, but not of interest to the public usually. It would be of interest to the seismologist. Any time -- that's what we call induced seismicity, seismicity induced by a dam or something like that. These are small earthquakes, magnitude 1, 2. Nothing anybody is typically gonna feel. But things we could record.

CAVANAUGH: I am speaking with doctor Debbie Kilb, seismologist from Scripps institution of oceanography, about a new research study that Scripps has released about lake load and its influence on earthquakes along the San Andreas fault. How would San Diego, doctor Kilb, be affected by a megaquake, a massive quake that occurred at this end of the San Andreas?

KILB: Another thing we need to consider is which direction is that rupture gonna go? Is it gonna go from the south to the north? If it does, you can think of the energy being pushed to the north. A lot of the energy is going up toward Los Angeles. If instead it went from the north to the south, that energy is going to be pushed to the south going down toward Mexico. Either way, Los Angeles or Mexico, San Diego is sitting in a relatively pretty spot as far as things go.

CAVANAUGH: That's good to hear. We heard something about a massive quake, a 7.9 quake near the Salton Sea liquifying our aquifers or something like that. Would that happen?

KILB: Yes. When you get strong ground shaking, if there's a lot of loose material, sand type of things embedded within water, you can get liquefaction. You can imagine being by the seashore, and if you do a fancy little footwork there and dance around, eventually your feet will sink down. The same thing is gonna happen if the seismic waves come by. They'll liquify beneath you, and that could cause problems. The exact same thing happened in 1929 in the San Francisco marina district.

CAVANAUGH: Robots might that happen in San Diego?

KILB: The large bodies of water and where is the silty materials that are with water. So around the bay area, around the Salton Sea definitely would be a problem.

CAVANAUGH: Your research shows that two fingers of the San Andreas fault were recently discovered under the Salton Sea. How are researchers discovering lines like that?

KILB: If you're a geologist, walk around the surface of the earth and figure out where the faults might be. If it's under water, what are you gonna go in your SCUBA tank? The Scripps institution of oceanography has a new technique, something called a chirp, essentially, it's like taking a sonogram of what the sediment looks like below. It's tedious working but it's very exact work.

CAVANAUGH: There have been recent clusters of small earthquakes under the Salton Sea as well. Does that tell you anything?

KILB: Those happen all the time. It's because we're within this region of high thermal behavior. Quite often we get swarms of earthquakes at that location. Not out of the norm. We saw that I think back in 2005 and 2,001 I believe.

CAVANAUGH: There's an awful lot of research going on in the field of earthquakes. And that devastating tsunami in Japan earlier this year makes people more concerned about this topic. Where are we in our ability to predict earthquakes?

KILB: The technology is just taking off. We can have seismometers in places where we might have have them before. We can see details in the seismograms we never could see before. Instead of playing the prediction game, what we're playing now is that we have the technology where we could measure the large earthquake coming in at one location and send that information fast enough to the infrastructure, folks that manage the infrastructure, to shut down the power, to shut down the BART train, things like that.

CAVANAUGH: That's fascinating. We read, I remember when the Japan earthquake was happening, and all those concerns about nuclear power plants, we were reading about some research being done off shore here in Southern California and new information about faults that may lie off shore. Is that research being conducted?

KILB: Research is being conducted like that. For me as a seismologist in Southern California, a lot of people talk about the rose canyon fault. For a seismologist, that's not of interest to me because there's hardly seismicity in that region along that fault. The rose canyon and nonseismically active faults up to the geologists, then we come in and share our information.

CAVANAUGH: What about those off shore faults though? Has anything new been found about that?

KILB: Not to my knowledge.

CAVANAUGH: Does this research open the doors to what other problems water weight could create?

KILB: Yes, it does open the door, and opens our eyes to the fact that we have to worry about these smaller faults. The faults in the Salton Sea region, they may be capable of a magnitude six or so. Nothing too big. We do have to start thinking about them in terms of a triggering sequence. What could that magnitude six then cause? And again we have the technology where we can map these, we can do the computer models and find out what regions are perhaps more hazardous and what regions report.

CAVANAUGH: When we talk about the Colorado river diversion having perhaps affected the natural cycle of earthquakes in that area of the San Andreas, fault we're talking about a diversion that kind of happened over a hundred years ago, right? So I guess just generally, you'd say why hasn't something happened already? But a hundred years isn't that long in geological time?

KILB: That's correct. And also the lake load from that diversion is relatively small compared to the prehistoric lake loads we've been talking about. The lake load that we've been talking about is about a hundred meters of sea level, whereas the diversion is only maybe 20. So that's -- that man-made influence is relatively small, and really in the noise for our study. We're more interested in the ones much more in the past.

CAVANAUGH: Where will you be going with this information, doctor Kilb?

KILB: I think what we're doing now, this is just putting forth one hypothesis. What could explain the 300†years? This is one hypothesis. Since we only have earthquakes every hundred years or so, we could just sit and twiddle our thumbs and wait for the next one. Instead we're saying where's a similar step over zone like this? Where is a lake where we might have these magnitude sixes that could trigger something else? We're going to different regions to figure out, is this something that could be common place in other regions. And how do we best prepare for it?

CAVANAUGH: I to thank you for speaking with us. I have been speaking with doctor Debbie Kilb, seismologist from Scripps institution of oceanography, and thank you very much.

KILB: Thank you for having me on. Have a nice day.

CAVANAUGH: Thanks.