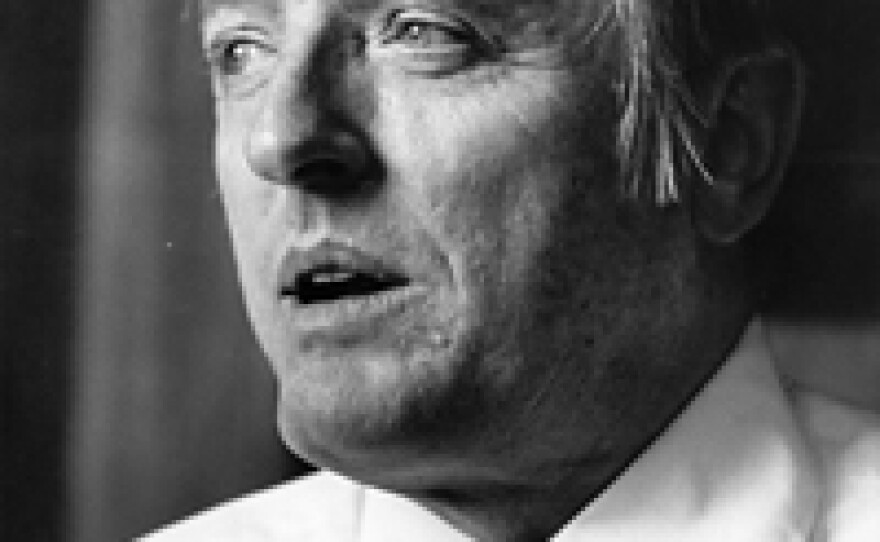

William F. Buckley Jr., the peerless and exuberant voice of the conservative movement, died Wednesday morning at the age of 82.

His son, the author Christopher Buckley, said his father died at his desk, at his home in Stamford, Conn., from complications of emphysema and heart disease.

As a young man, Buckley parlayed his anger at the secularization of American society into a book, God and Man at Yale, and then into National Review, the magazine that became a rallying point for conservatives.

A 'Silver-Tongued, Witty' Guy

"When he burst onto the scene in the mid-1950s, the image of the conservative was someone who didn't care about ideas — kind of a cigar-chomping industrialist that only cared about his own profits," said Rich Lowry, Buckley's hand-picked successor as editor of National Review.

Lowry says Buckley offered a new champion for conservatives dispirited by the insufficiently ideological administration of President Eisenhower.

Buckley was, Lowry said, "an Ivy League-educated, silver-tongued, witty and erudite guy who could take on all comers — and he had just an incalculable influence."

In an interview on NPR's Talk of the Nation in 2004, Buckley explained his magazine's initial appeal.

"In the late '50s, when National Review was born, there were a lot of people who wanted something to read that was well-informed and staunchly and unapologetically anti-communist and anti-socialist — and National Review did that," Buckley told NPR's Lynn Neary.

Values Rooted in Christian Tradition

Buckley also argued for social values rooted in Christian traditions — and against the regulation of business and the economy. His debates with counterparts on the left — such as Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer — evolved into the long-running PBS show Firing Line, which was considered a home for lengthy, reasoned discourse and disputation.

Buckley began his career with a brief stint at the CIA. He was a sailor throughout his life, but he saved plenty of time for writing. His point of view emerged not just in the pages of his magazine, but in 45 books and 5,600 newspaper columns. In a commentary for the NPR series This I Believe, Buckley talked about his own faith — a deep Catholicism. Buckley began it by citing the story of a scholar's rebuttal to skepticism about the existence of God.

"The imperishable answer was, 'I find it easier to believe in God than to believe that Hamlet was deduced from the molecular structure of a mutton chop,' " Buckley said. "That rhetorical bullet has everything — wit and profundity."

Remaking the Conservative Movement

Above all, his son Christopher Buckley recalled Wednesday, William Buckley sought to make it respectable to be a conservative.

"He drove out the kooks of the movement," Christopher Buckley said. "He separated it from the anti-Semites, the isolationists, the John Birchers. He conducted, if you will, a kind of purging of the movement."

Buckley helped establish Young Americans for Freedom — who formed the core of Barry Goldwater's unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1964. But the movement found a new standard-bearer in Goldwater's ally, Ronald Reagan, who won the White House 16 years later.

"I have heard it said on many occasions — if there hadn't been a Bill Buckley, there would have been no Goldwater — and if no Goldwater, then no Reagan," Christopher Buckley said.

William Buckley later regretted some of his positions — such as his unyielding opposition in the mid-1960s to landmark voting rights bills. But Buckley took pride in seeing his influence spread as the modern conservative movement took hold.

Over the past year, as his health declined and as he mourned the death of his wife, Pat, Buckley's life became much tougher. Christopher Buckley paraphrased Shakespeare in thinking about his father's life and death.

"I sent out an e-mail this morning to ... his friends," Christopher Buckley said. "And I found myself unable to resist quoting that line from Hamlet: 'Take him for all he was worth, Horatio. He was a man, and I shall not look on his like again.' "

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))