U.S. employers added more jobs last month than at any time in the past four years, but the brightening labor picture prompted hundreds of thousands of people to start looking again, forcing the unemployment rate up to 9.9 percent.

The Labor Department reported Friday that payrolls expanded by 290,000 jobs -- about twice what most analysts had expected. About 66,000 were temporary government positions for people hired to conduct the census, while the private sector accounted for an unexpectedly robust 231,000 jobs.

As more companies begin hiring, people who sat on the sidelines when employment prospects were grim have resumed their searches.

Some 805,000 job seekers jumped back into the market in April. Because the unemployment rate only counts people who are actively looking for work, that caused the number to edge up from 9.7 percent in March. The rate hit 10.1 percent in October, a 26-year high.

"When you look at the employment report from 20,000 feet, it's all good numbers," said Brian Wesbury, chief economist at First Trust in Chicago. "What happened [with the higher unemployment rate] is that people rushed back into the labor force," he told NPR.

"That will slow down and we will see the unemployment rate come down. But in order for that to happen, we need job gains and we are getting that now."

Manufacturing payrolls made the strongest gains -- 44,000 jobs, compared with 19,000 in March. Construction gained 14,000 jobs, and retailers, professional and business services, education and health services, leisure and hospitality, and government all showed gains. Among the weak spots: transportation and warehousing, and information companies, which all cut jobs last month.

The employment picture also turned out to be stronger than previously thought for both February and March. Payrolls grew by 230,000 in March, better than the 162,000 first reported. And 39,000 jobs were actually added in February, an improvement from the previous estimate of 14,000 losses.

The strong U.S. jobs data failed to shore up confidence in world markets following days of extreme volatility. Markets dropped in Britain, Germany, France and all across Asia.

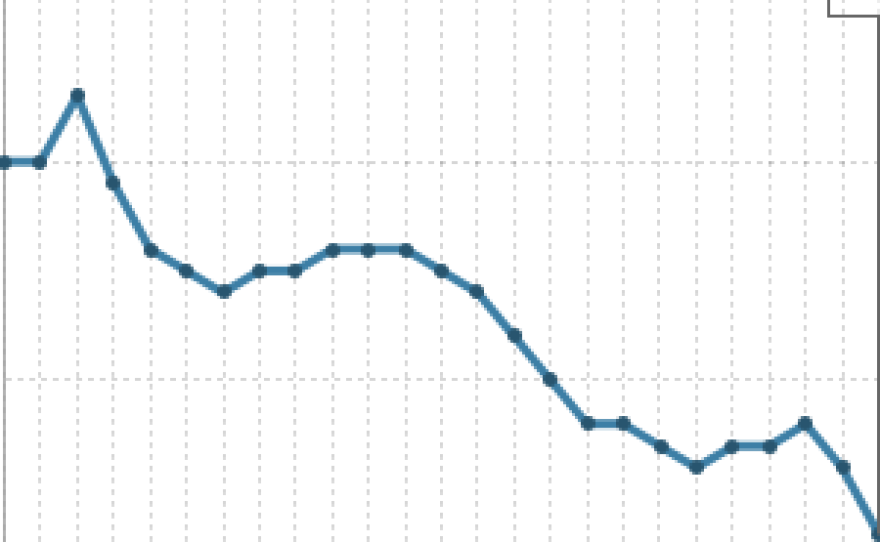

On Wall Street, the Dow Jones industrial average was down more than 180 points at one point during morning trading, while the Nasdaq and Standard & Poor's 500 indexes also dropped.

The declines came on the heels of a tumultuous showing Thursday in which the Dow plummeted nearly 1,000 points in 15 minutes. The index briefly fell below 10,000 before recovering most of the losses.

That record point drop was initially blamed on Greece's deteriorating economic and political situation and fears that the European debt crisis could spread and derail the global economic recovery. It was later discovered that a computerized sell-off, which might have been triggered by a simple typographical error or "fat-fingered trade," may have been the main culprit.

"There are still major risks to the global economy from the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone and high unemployment acting as a drag on consumer spending in the U.S.," said Charles Davis, senior economist at the Centre for Economic and Business Research.

President Obama called the employment figures "particularly heartening when you see where we were last year -- with an economy in free fall."

But the president acknowledged there are still "a lot of people out there experiencing real hardship."

"Yes, we got a ways to go, but we've also come quite a ways already," he said.

Of those people who re-entered the labor market, 550,000 of them found jobs, according to the survey of households used to calculate the unemployment rate, said Alan Levenson, chief economist for T. Rowe Price in Baltimore.

That was about twice the 290,000 figure reported by the survey of business payrolls, Levenson told NPR.

Even so, some 15.3 million people remained jobless in April. Counting those who have given up looking for work and part timers who would prefer to be working full time, the so-called underemployment rate rose to 17.1 in April.

"The economy shed 8 million jobs during this recession, and some of those you could argue are not going to come back very soon at all," Levenson said.

Hourly wages were up slightly last month, to $22.47 from $22.46 in March. Without increased hourly earnings, most Americans will be reluctant to increase their spending, which accounts for about two-thirds of the U.S. economy.

In turn, for employers to boost hiring significantly, the economy would need to grow at an annual rate of 6 percent to 8 percent a quarter. Instead, economists say, it has gained just 3.2 percent pace in the first three months of this year.

The average workweek rose to 34.1 hours from 34 hours in March.

Material from The Associated Press was used in this report

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))