Journalists have spent many days and millions of words hashing over the news that banking giant JPMorgan Chase lost billions of dollars trading "synthetic" derivatives.

I am one of those journalists who, more or less, can understand what the bank says it was trying to do, i.e., hedge against loan losses. But here's what I have a hard time explaining:

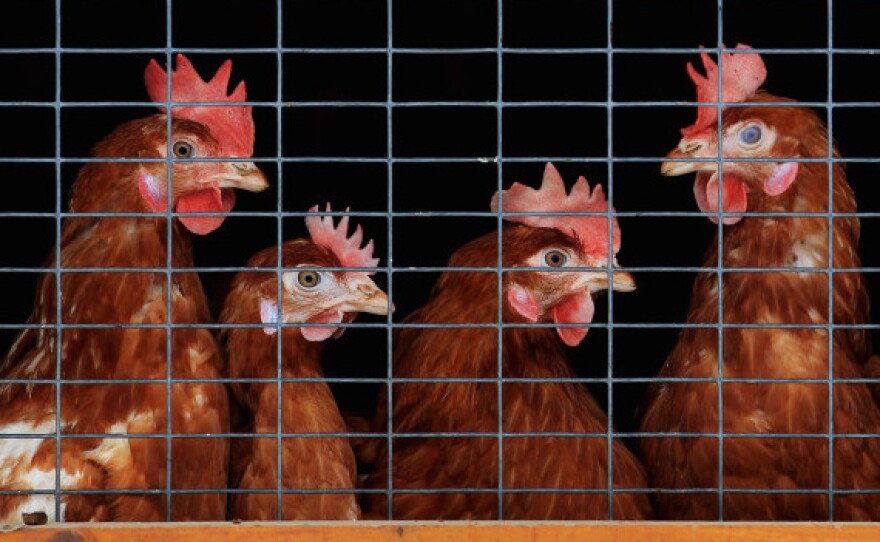

What does this kind of complex trading have to do with the price of eggs?

In the past, you could ask what big bankers on Wall Street did for a living and get an answer that made sense in terms of the "real" economy. Their job was to help investors buy and sell stocks, and those transactions could spur companies to grow.

Consider the investors who — back in the 1970s — purchased shares of Bob Evans Farms Inc. Wall Street firms helped trade shares of the breakfast-oriented restaurant chain, which grew into a huge employer with more than 700 locations. I can see how Wall Street helped connect me with my breakfast eggs at Bob Evans.

Wall Street still does straightforward stock deals like that — for instance, Facebook's initial public offering. But in addition to helping buyers and sellers exchange stocks and bonds, today's traders also do transactions that are far, far more complex. Some involve "synthetic" derivatives.

As JPMorgan has demonstrated, such transactions can break bad and end up costing a bank a fortune. But what about when they go right? Do these transactions ever do anything to help average people?

For an answer, I went to Matthew Jensen, an economic researcher at the American Enterprise Institute. I asked him: "What does synthetic-derivative trading have to do with the price of eggs?" He made up a company, Chickens LLC, and we headed off together to see how this works:

Step One: Understand what a derivative is.

This term refers to a financial product that derives its value from an underlying asset. For example, corn is an asset. A derivative could be a contract to buy or sell corn in the future at a set price. So a contract that allows you to, say, buy corn at a low, fixed price could become very valuable if a drought were to drive up the price of corn. A derivative like that could help a cereal maker sleep better at night, knowing he's not going to have to pay a fortune for corn if the weather turns dry.

Step Two: Understand what a "synthetic" derivative is.

This type of derivative attempts to replicate what some other — more annoying — financial product might do. The goal is to accomplish the same financial mission, but with fewer hassles. So, say you don't want to actually enter into a contract on the future price of corn, and you certainly don't want to take possession of corn. Instead, as Jensen put it, you could "cobble together some other assets to mirror the performance" of a contract to purchase corn.

It's like assembling a Fantasy Corn League, where people can place side bets on how the real corn prices are going to move — up or down. To create these purely financial products, a Wall Street firm could package up just-invented options that mimic the payout schedule and characteristics of real futures contracts, and the investors would never have to worry about the complexities that come with entering into an actual contract to buy real corn.

Step Three: Understand why anyone would play this game.

Jensen says these transactions "can provide flexibility to investors because any aspect (payoff schedule, yield, exposure to interest-rate risk, etc.) can be modified, without having to find the perfect asset in the existing market." In other words, if you are worried about only one thing, such as the direction of interest rates, these kinds of synthetic investments can help you offset that specific risk — just as buying traditional options can help protect farmers and cereal makers worried about corn prices.

Step Four: Think about our imaginary company.

Say Chickens LLC wanted to expand, so it borrowed money using a floating-interest-rate bond. By borrowing money, our imaginary company could acquire more hens and more corn for feed to produce more eggs, Jensen explains.

But the owners of Chickens LLC are worried about interest rates rising because they haven't yet entered into a contract to sell their eggs. They don't want to pay more for the borrowed money — especially not until they know for sure what price they'll get for their eggs.

They could just sit there and take their chances — hoping the eggs will sell high and interest rates stay low. But sitting around being nervous doesn't exactly encourage hiring.

Instead of the do-nothing approach, the owners could construct a synthetic derivative out of their existing bond and an additional derivative product. As Jensen says, Chickens LLC "can find one other party with opposite risks, and enter into an interest-rate swap for the exact amount of time needed to match the time to maturity" of its existing bond.

Now, of course, as with any transaction, things can go wrong — very wrong. Earlier this week, JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon said his company's derivative-trading strategies were "flawed, complex, poorly conceived, poorly vetted and poorly executed." Ouch.

That's how banks and their investors can lose billions of dollars in a very short time. But when the sophisticated financial products and trades go well, the profits can be enormous.

Step Five: Again, what does any of this have to do with the price of eggs?

Let's go back to Chickens LLC and assume that it did not use flawed, poorly conceived synthetic derivatives. Let's assume it properly hedged against interest-rate risks, and now the owners can feel more confident.

Knowing they have well-constructed synthetic derivatives on their side, they don't have to hoard cash and fear the worst. Instead, they can be more confident about hiring workers, and they can go ahead and "lower prices on eggs," Jensen says.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))