The women who came forward to accuse former Mayor Bob Filner of unwanted sexual advances stepped into a glaring spotlight. They became targets for a hungry media machine, anxious for every salacious detail. At times they became targets in another way, with people accusing the women right back, claiming they had ulterior motives, such as certain political leanings, greed or self-aggrandizement.

The critics’ implications were clear: they believed these women were “selling” their stories in the marketplace of a media frenzy, that they were part of a witch hunt. Some people wondered if Filner was being pushed out of office by forces unhappy with his progressive agenda. Others said they believed the women who spoke out were part of a conspiracy to unseat the first Democratic mayor of San Diego in decades.

On the day the mayor resigned, many Filner supporters spoke up during a special meeting of the city council.

Labor activist Joan Raymond wondered why the women had only come forward now.

"I was brought up to be a strong woman and to immediately put a man in check if he was getting out of hand, not to wait and jump on a political band wagon," she said.

Some who spoke, especially those from marginalized communities, said they felt Filner had given them a voice for the first time.

Maria Ochoa said through a Spanish translator, "If we know that the laws are very delicate for sexual harassment, why did they wait so long, who paid them off, why did they make these accusations now?"

There is a legitimate question about why and when the women came forward with their claims. Part of that question is why it is so hard for victims of sexual harassment, mistreatment and abuse to come forward. It was a question I also asked as I reported this story.

The answer in part can be found in what these woman experienced after they told their stories. The accusations they faced and the doubt their claims received is part of the reason coming forward is not an easy equation.

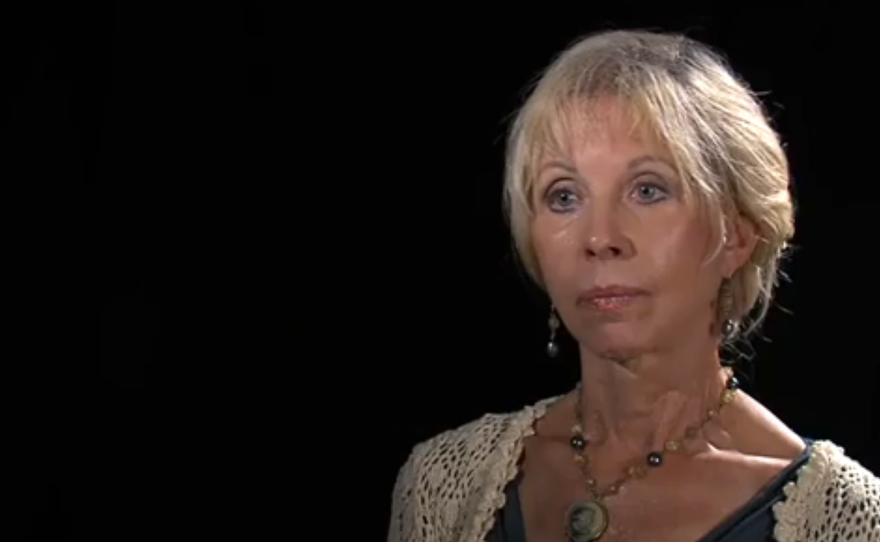

In the back of the council chambers on the day of Filner's resignation sat Peggy Shannon, a city hall employee who came forward to accuse Filner of inappropriate behavior.

"I just wanted to sit back here and listen," Shannon said. "They’ve heard me, they’ve seen what I had to say. I didn’t want..." Shannon paused, "to be perfectly honest, I didn’t want to be booed," she said with a laugh. She knew it was an emotional room.

"They've booed other people," she said.

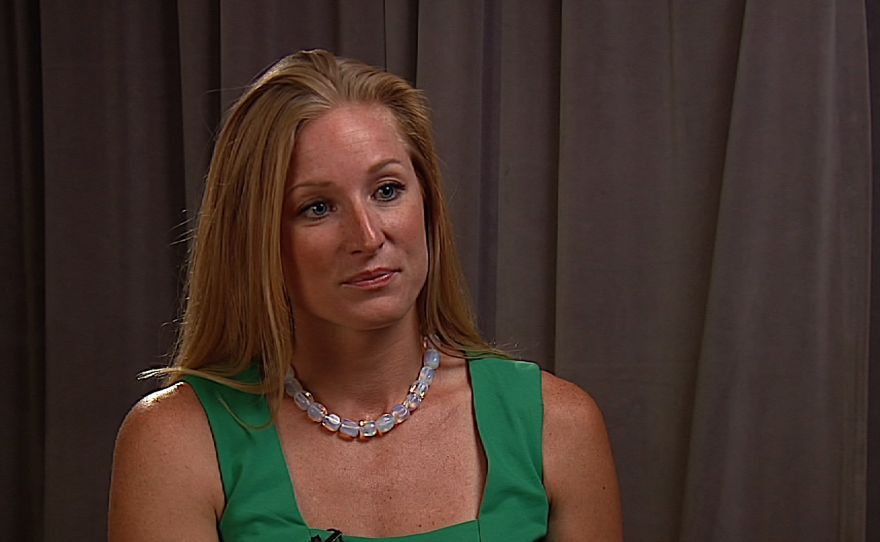

One woman who had accused Filner did approach the podium to give her perspective. Laura Fink, the second woman to publicly accuse Filner reminded the council to think of the women who have been his alleged victims.

Fink said the questions many Filner supporters raised — asking why the women only came forward now — were ones she had heard many times before.

She said women don’t come forward because “they understand the disparity in power, I think they also believe they will be dismissed, that their character will be attacked, or that they wont be believed, and all of those things happened to me.”

But why didn’t she come forward sooner? For Fink, the answer is simple: She came forward when the topic began to be discussed publicly, when former supporters of Filner reached out in press conferences to support the women. When she felt her story would count, when it would mean something, Fink did come forward.

Before that, Fink said, she felt like what happened to her happened in a bubble and she just didn’t think any one would take her word.

“There is strength in numbers,” she said. “I imagine what it would be like if I was the only one coming out, and people ask these questions, 'Why didn’t you come out sooner? Why didn’t you come out during the campaign?'”

Fink said until Donna Frye, Marco Gonzalez and Corey Briggs — the former Filner supporters — began to speak up for the as yet unnamed women, all she felt she could do was scream in the dark.

“You as an individual, as a person have to do a calculus as to whether your coming forward will be effective and impactful and believed,” Fink said. She said she believed if she had spoken out on her own earlier, “I probably would have been really eviscerated and my motives would have been questioned far more than in this situation.”

Morgan Rose was the third Filner accuser to come forward this summer. She said speaking out was at first an agonizing decision.

“You can be very vulnerable to crucifixion and character assassination by people who have never ever spent a minute with you” she said. “That happened and that’s OK. That’s not the important part.”

The important part for her, she said, is that the man she felt had violated her is no longer in office.

What happened to Rose happened in 2009. So why did she stay silent in the intervening years?

“He was a Congressman,” she said. “He already had my home phone number. He could get my social security number, my home address, my place of work. So no, I was not going to come forward at that time.”

This time, Rose said, she felt she could come forward in part because other women had spoken out, in part because the swell of accusations had risen to a fever pitch. Both Rose and Fink said it was far easier to join a conversation than to start one they felt would inspire only backlash.

Both women said they felt compelled to speak because they knew there might be women who still could not. They wanted to give a voice to what they now see as not their own story, but the story of many women who had been the recipient of unwanted sexual advances by Filner.

Rose said it still wasn’t an easy choice.

"Any woman in this position, in this kind of drama — we’re in a lose-lose situation often — but with us all coming forward, that theme, that pattern became so evident,” she said. “People that might not have believed our story initially or thought it was for political reasons, had to start admitting, 'No, maybe we have something here.'”

Rose said making herself a public figure — and in this case, a public victim — carried with it repercussions. After Rose gave her first interview to KPBS, she went away on an already scheduled vacation. Even half way across the world, she was still recognized. There was no escaping what she had done.

For Fink, the scrutiny was fast and furious. Soon after she left the interview we did in the KPBS studios, she learned that news vans were waiting outside her apartment.

“There were reporters yelling into my apartment,” Fink said. “Yelling my name, bothering my neighbors, banging on the door — it was frightening. I just didn’t realize how intense the coverage was going to be.”

Fink had to sneak out to spend this night at a friend’s house.

Fink said coming forward and speaking out opened up a conversation beyond what she had expected. Women would approach her on the street and tell her their stories of harassment. Female journalists who interviewed her would start off by confessing that it happened to them. Friends she had known for years would do the same. All of a sudden, Fink said, sexual harassment was everywhere.

“It was frightening how pervasive this behavior is across the board,” Fink said. “It took me aback, because I thought—is this the world we are leaving to our daughters? Where sexual harassment is a rite of passage, where its rare if it doesn’t happen to you? It’s just extraordinarily upsetting.”

Fink’s normally confident voice was cracking, but then she looked at me and smiled.

“We hope we can change that,” she said.