You can learn more about the propositions proposing changes in San Diego charter language in our voter guide propositions proposing changes in San Diego charter language in our voter guide@KPBS.org/election. In her campaign for Barbara Boxer's U.S. Senate seat California Atty. General. Pamela Harris often mentions the record settlement her office negotiated with lenders after the home foreclosure crisis. The deal one national media attention for Harris to the mortgage Matan continues affecting California homeowners to this day is part of our California Counts election coverage KQED to Devon Katayama examined for the release dollars went and Harris's role in the settlement. In the home are sorry of free see rents there aren't many decorations on her walls. I don't feel like hanging my pictures in there or having my home more homely because this is not my home. The home she once owned it's not far from here at the foot of these grassy hills in the Bay Area city of Antioch. This is my neighborhood. We love the hills. In 2009 Frisse lot the page has a quarter after adjustable mortgage which is to pray she can afford . She says her husband was working with the bank to change the loan and at one point the bank was working with them on another offer. The offer never came. These Senator. announced in 2012 was supposed to fix the way banks communicated and work with struggling homeowners like Frisse . Harris got a lot of credit for the role she played. Here is played a bad hand relatively well. Journalist David Dain's new book chain of title examines the mortgage crisis. He followed the national settlement closely is this the bank should of been prosecuted. Instead he says the states were too quick to settle. This is finally a bit of leverage over the financial industry on the behalf of homeowners that we did not see at any other point in this crisis, certainly not to disagree. The prosecuting would take time and dances even if Harris wanted to fight the banks there needed to be a bigger coalition not just her. At the same time Californians were losing their homes quickly so Harris settled. To make sure the banks would stick to the settlement agreement Harris appointed UC Irvine professor Katherine Porter. Paris wanted a really strong agreement and one that could be enforced. She also was balancing the fact that people needed help now not tomorrow. Porter says media focus on the billions of dollars in the settlement but Harris is real achievement where the reforms she helped push the legislature. The homeowner Bill of Rights meant that all banks and lenders had to obey the new rules not just the top five in the settlement. The servicing standards helped everybody, every homeowner. That housing counselors say some lenders in California are the of violating the reforms that were intended to be permanent. Under the reforms homeowners can actually sue but David Dayen says that should be Harris's job. The entire purpose of a settlement of this kind presumes that the misconduct being settled stops in it has not. In the and about half of the settlement dollars went to short sales. That's what people lose their home but are able to save their credit. The smallest amount of relief dollars were for the most important type of relief, reductions of the homeowners first mortgage to allow them to stay in their homes. A majority of people got the 1500 bucks that were sorry of free see got. That was like a slap in the face for a lot of us. We don't get happy when we receive it, we just get more mad. Since the national settlement here is has reached other smaller related agreements with lenders. A spokesman for Harris's U.S. Senate campaign said she would continue her fight to prevent the risky practices that caused the financial collapse but he declined to give specifics. I'm Devin Katayama in San Francisco.

In her campaign for Barbara Boxer’s U.S. Senate seat, California Attorney General Kamala Harris often mentions the record settlement her office negotiated with five of the largest mortgage lenders after the home foreclosure crisis.

The deal that brought about $20 billion in relief to California won national media attention for Harris. But the mortgage meltdown continues affecting homeowners to this day.

In the home Rosario Frisse rents in a quiet neighborhood in Antioch — a city about 45 miles east of San Francisco — there aren’t many decorations on her walls. Even though she’s been living there for a few years, there are unpacked boxes on her patio outside and more in the garage.

“This is not my home,” she said.

The home she once owned sits about a mile away.

In 2009, Frisse lost the house after her adjustable mortgage was raised to an amount she couldn’t afford. Her husband was working with the bank to modify the loan. At one point working out a deal looked promising and they were waiting on an offer from the lender, she said.

“The offer never came.”

Instead, the lender foreclosed on Frisse’s house and it was sold at auction, she said.

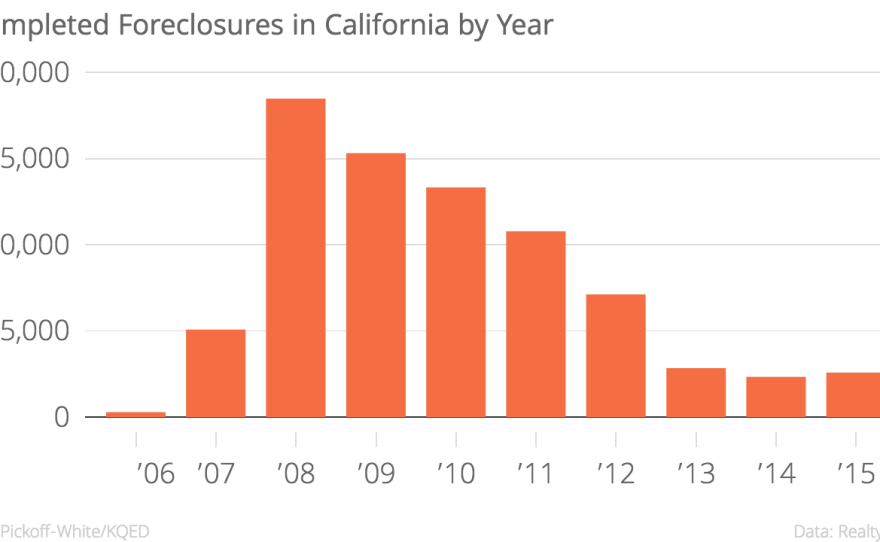

That year, 632,573 Californians received a foreclosure filing, including a default notice, scheduled foreclosure auction or bank repossession, according to RealtyTrac.

The national settlement that was announced in 2012 was supposed to provide some debt relief to homeowners and fix the way banks communicated and worked with people like Frisse, whose homes were in jeopardy of being foreclosed. Attorney General Harris was crucial to negotiating the national settlement’s terms, since California had the country’s highest number of foreclosures. She even refused to sign onto an initial deal because it wasn’t enough money. But eventually she would settle.

Harris was in a no-win situation

“Harris played a bad hand relatively well,” said journalist David Dayen, whose new book, “Chain of Title,” examines the mortgage crisis.

Dayen also followed the national settlement closely and is part of the group of critics who believe the banks should have been prosecuted. There was certainly enough evidence, he said.

“This was finally a bit of leverage over the financial industry on behalf of homeowners that we did not see at any other point in this crisis, certainly not to this degree,” said Dayen.

But prosecuting would take time. Plus, even if Harris wanted to fight the banks, there needed to be a bigger coalition — not just her, said Dayen.

Meanwhile, Californians were losing their homes. In 2012, Harris and 48 other attorneys general settled with five of the largest mortgage lenders, including Ally Financial, Bank of America, Citi, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo.

In the end, the banks provided about $20 billion in relief to California. The lenders were credited for providing certain types of relief.

About $9.2 billion went to short sales. That’s when people still lose their home but the impact is less damaging to the homeowner’s credit than a foreclosure.

Around $4.5 billion went to debt relief on the second mortgage.

The best possible type of relief homeowners got was debt relief on the first mortgage — known as first mortgage principal reduction — which attempted to bring the value of the loan down to the value of the home. Roughly 33,000 homeowners received an average reduction of $137,280.

But for all the settlement relief that homeowners received to help them stay in their homes, the smallest number got a first mortgage reduction.

The most widely distributed relief, which was given to about 200,000 homeowners, was the $1,500 in restitution that Rosario Frisse got.

“That was like a slap in the face for a lot of us,” she said.

More than just the cash

One of the best things Harris did, according to Dayen, was to appoint UC Irvine professor Katherine Porter to lead the special monitor program. Her job was to hold the lenders accountable over the settlement period.

“I took calls on day one,” said Porter.

In the end, her office responded to over 5,000 complaints. A website was quickly created for homeowners to check their eligibility in the settlement — something that wasn’t done at the national level. Porter and others also spoke with attorneys and judges who needed help understanding the settlement’s terms, she said.

Porter told KQED the media were focused on the billions of dollars in settlement money, but Harris’ real achievement was the reforms she was pushing for simultaneously in the California Legislature.

When it was passed in 2012, the Homeowner Bill of Rights meant that all banks and lenders had to obey the new rules, not just the top five lenders in the settlement. The reforms meant there is now a single point of contact to prevent miscommunication. There are restrictions on dual tracking, which prevents foreclosure on homeowners who are in the process of modifying their loans. And homeowners were given the ability to sue lenders.

“The servicing standards helped everybody. Every homeowner,” said Porter.

For the most part, banks and lenders were making more of an effort to change under the settlement, she said. But when housing counselors were asked how the banks are doing now, four years later, some have said lenders are still violating the reforms that were intended to be permanent.

“In my view that’s grounds for new prosecution,” said Dayen.

Since the national settlement, Harris has reached other smaller related agreements with lenders. A spokesman for Harris’ U.S. Senate campaign said she would continue her fight to prevent the risky practices that caused the financial collapse, but he declined to give specifics.

Harris has used her power in other ways. She recently wrote a brief on behalf of a homeowner in a case that went to the California Supreme Court. She also put her shoulder into a law that would cover widows, widowers and other survivors in the Homeowner Bill of Rights.

The settlement is hard to measure

There is still no true accounting of whether the government did enough to help struggling borrowers during the foreclosure crisis, according to Carolina Reid, a UC Berkeley professor who studies the impacts the foreclosure crisis had on communities of color.

Federal data exist on who gets loans, and we know that African- American and Latino families disproportionately got the worst loans. But we don’t know much about the families who get loan modifications, even those who were helped from the settlement. There’s no race or neighborhood data.

“It would have been great to look at each of the loan modifications and understand who got them and more importantly who didn’t,” she said.

The amount of mortgage lending to African-American and Latino families has dropped since the recession. Banks are almost too cautious in some cases and not lending to some families who would make great homeowners, she said.

Rosario Frisse saw some friends and neighbors keep their homes because of the settlement. It was a celebration when they did, she said.

Beginning in 2009, the year she lost her house, she fought hard on behalf of homeowners. She caravaned with a group called Contra Costa Interfaith Supporting Community Organization to Washington, D.C., to protest the banks, and she spoke at rallies.

That didn’t help her save her own home.

Frisse said her husband now wants to move back to Missouri, where there’s family. She wants to stay in California. But at the same time there are no pictures on her walls. And there are still unpacked boxes that tell her she’s not home yet.

Copyright 2016 KQED.