For years, San Diego’s highest-paid city employees have been the same group of police officers who work thousands of hours of overtime and earn substantially more than top city officials, according to a KPBS analysis of city salary records.

The highest-paid city employee in 2023 — the most recent year with complete compensation data — was a cop who worked upwards of 3,000 hours of overtime and earned over $430,000 in total compensation.

By comparison, the mayor earned $234,000 that year. The chief of police earned $310,000.

Have a tip? 📨

The Investigations Team at KPBS holds powerful people and institutions accountable. But we can’t do it alone — we depend on tips from the public to point us in the right direction. There are two ways to contact the I-Team.

For general tips, you can send an email to investigations@kpbs.org.

If you need more security, you can send anonymous tips or share documents via our secure Signal account at 619-594-8177.

To learn more about how we use Signal and other privacy protections, click here.

Data from the first nine months of 2024 show multiple San Diego Police Department (SDPD) officers were again on track to make over $400,000 — with the bulk of it from overtime pay.

The staggering salary figures underscore the department’s struggle to fill officer vacancies and its desperate need to cover shifts. Beyond the fiscal considerations, there are also serious safety concerns. Research shows officers who work very long shifts with limited rest in between are more likely to get in accidents and make bad decisions when pursuing suspects or using deadly force.

“It’s very concerning,” said Paul Parker, former executive director of San Diego’s civilian police oversight commission. “You have to consider that these folks are armed and they're tasked with making split-second decisions.”

A 2024 city audit found officers sometimes work shifts lasting more than 19 hours. Research suggests working for that long results in impairment similar to drinking several beers.

These cops are the outliers when compared to the rest of the department. According to the audit, 50 officers worked more than 1,000 hours of overtime in fiscal year 2023, and only a handful worked more than 1,500 hours. The typical officer worked 181 hours of overtime, or about 3-to-4 hours every week.

SDPD Chief Scott Wahl described overtime as essential to keeping the department functioning — “(it) is our life blood right now,” he said. He also isn’t bothered by some of his officers earning huge amounts of overtime pay, which puts their compensation way past his annual earnings.

“They put in a tremendous amount of hours,” he said. “They earn the money that they've made.”

But Wahl does believe some safeguards should be put in place. The department currently has no limit to the number of hours an officer can work in a shift. Wahl says he would support a limit to shift lengths and minimum break requirement between shifts. He also wants to roll out a centralized system to approve and track overtime.

With the city facing a budget deficit of more than $300 million, the chief is walking a tightrope. The department expects to go roughly $10 million over its original overtime budget this fiscal year, matching a trend from the last decade. That would bring overtime spending to about $56 million.

Wahl recently proposed trimming the overtime budget for next year by millions, but City Council members balked at the suggestion, fearing overtime cuts could hamper public safety at a time when the department continues to struggle with call response times.

“I feel that we’d be putting people more at risk if we did cut overtime,” said Councilmember Marni von Wilpert at a hearing in early May.

A spokesperson for Mayor Todd Gloria did not respond to a request for comment.

The $430,000 officer

More than a decade ago, no San Diego cop made more money than the police chief, according to public employee compensation data gathered by the state.

But in 2015, that started to change. Police officers steadily racked up increasing amounts of overtime hours and the premium pay that came with it. By 2020, police officers topped the list of the highest-paid city employees (a designation that, for years, was held by firefighters working a lot of overtime).

No one embodies this drive for overtime more than officer Jason Costanza, who’s been on the force for over a decade.

Costanza was the highest-paid city employee in 2023, earning $433,000 in total compensation, according to SDPD salary records. He earned $108,000 in base pay and $286,000 in overtime pay. (The rest of his compensation was in the form of “other” or “lump sum” pay, which can include vacation payouts, car allowances, stipends, bonuses, etc.)

Costanza was the highest-paid city employee in 2022 and the second-highest in 2021, the data show.

As an officer with a lower base pay, Costanza has to work a colossal number of extra hours to beat out higher-paid sergeants who also rack up a lot of overtime.

Colossal as in: 3,151 hours of overtime in 2023, according to records obtained by KPBS.

It’s unclear what kinds of shifts Costanza picked up to log so many extra hours. But the city auditor’s report from last year sheds some light onto Costanza’s breakneck work schedule.

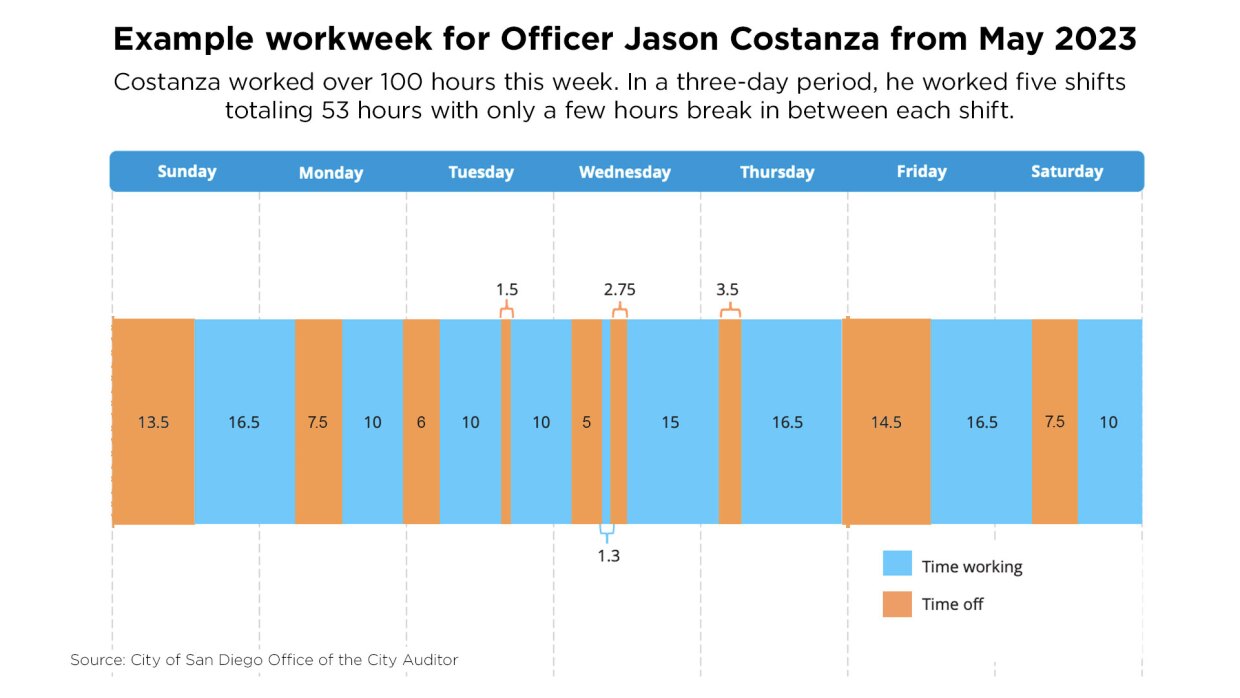

The audit includes an analysis of one unnamed officer’s schedule in 2023. The information is anonymized in the audit, but KPBS confirmed through public records requests that the officer was Costanza.

In one 28-day period in 2023, Costanza worked 439 total hours — that averages out to roughly 16 hours per day, seven days a week.

The audit also broke down a sample work week from that month. In one three-day period, Costanza worked five shifts totaling 53 hours with only a few hours break in between each shift.

“Eventually that's going to lead to burnout,” said Parker, who previously worked as a police officer and death investigator before transitioning into police oversight. “Burnout then comes with problems at home, problems with health, problems with decisions that they're making when they're interacting with members of the public.”

While the city audit highlighted the alarming number of overtime hours worked by some officers, it determined the department’s overtime authorization and tracking were accurate.

Wahl said some officers accumulate substantial overtime hours because they serve a specialized role in the department.

Sgt. Gary Mondesir, for example, has worked special events for years, such as Padres games and Comic-Con. He earned $405,314 in 2023 with the majority of it coming from overtime pay.

“Gary Mondesir does a phenomenal job of managing some very high-profile events,” said Wahl. “We never have an issue because he's professional and he's got a job-skill that very few people do.”

Mondesir was a lead plaintiff in a 2017 lawsuit that claimed the city was not properly calculating overtime pay. The lawsuit resulted in a $6.2 million settlement with over 100 officers.

Sgt. Michael Wallace is another cop who routinely ranks among the top overtime earners in the department. From 2021 and 2023, he earned between $202,000 and $256,000 in annual overtime pay.

SDPD declined to make specific officers available for comment. The San Diego Police Officers Association, the city’s police union, did not respond to requests for comment.

Wahl said other specialized areas that require overtime shifts include homelessness response and motorcycle patrol.

According to Parker, it makes sense for officers on special details to work more overtime hours. “But even then, thousands of hours of overtime seems to be excessive,” he said.

Dangers of fatigue

Parker said working excessive overtime can compromise an officer’s readiness in the field.

“I can speak from experience,” he said, recalling his time as an early-career officer in Youngtown, Arizona. “When you're working 14-, 16-hour days and then you put a couple of those days back-to-back … you're absolutely exhausted.”

Lois James, director of the Sleep and Performance Research Center at Washington State University Spokane, said the increased fatigue from multiple overtime shifts can lead to dangerous and potentially deadly outcomes.

“Officers who are particularly tired, they're less likely to de-escalate,” she said. “They're less able to manage crisis encounters.”

SDPD officers have a four-day workweek with 10-hour shifts, which is typical for many police departments.

According to James, the risk of accident, error and injury starts to go up after an officer’s eighth hour on duty. After 12 hours, research shows the risk of accidental death goes up by 110%. After 17 hours, an individual’s impairment is comparable to having a .05% blood alcohol concentration.

James acknowledges that overtime plays an important role in policing. It adds staffing flexibility and fills in vacancy gaps. But she says it can end up costing cities more in the long run.

“It's what we call the fatigue tax,” she said.

Excess overtime can lead to burnout and officers taking sick time, which can exacerbate a department’s overtime demands when backfilling shifts.

There’s also the liability risk of fatigued officers making mistakes on duty, which can lead to lawsuits or settlements. When those officers are pulled from patrol or terminated, it creates additional vacancies that need to be filled.

“It's easy for it to get into this vicious spiral,” James said.

One thing that can mitigate the risks of overtime, according to James, is a department nap policy that allows officers to take rest breaks on duty in a safe location. SDPD confirmed it does not have a nap policy.

Chief Wahl responds

Research suggests fatigued officers are more likely to face civilian complaints and overtime can result in more of use of force incidents.

A 2018 study from Washington State University’s Sleep and Performance Research Center found officers were seven times more likely to receive civilian complaints when working shifts that typically leave officers exhausted, especially night shifts. The study found the risk of complaints increases if shifts are worked back-to-back with little rest in between.

A 2017 audit in King County, Washington, found “uses of force are significantly correlated with overtime.” If an officer works just four hours of overtime in a week, the likelihood that they will be involved in a use of force incident the following week goes up by 11%. As officers work more overtime hours, the likelihood “increases exponentially.”

But Wahl resisted the notion that excess overtime increases the risk of harmful or negative interactions between his officers and the public.

“I don't think that the right way to answer that is to give you a ‘yes’ or a ‘no,’” he said. “I think there are so many factors.”

The chief said he doesn’t believe there’s a connection between fatigue and civilian complaints against his officers, and he isn’t aware of any complaints against the officers who repeatedly top the department’s overtime list.

“If they're not out there being respectful, treating people right, making good decisions, then they're going to be pulled back from working overtime,” he said.

Wahl said he trusts officers to know their work thresholds and trusts supervisors to intervene if they identify burnout. But he is open to setting some limitations, which would include capping shifts at 16 hours and requiring 8-hour breaks in between shifts, as well as mandating one day off per week.

“We do need to have some guardrails in place,” he said.

These proposals would have to go through a meet and confer process with the police officers’ union; Wahl hopes that process will finish by the end of the year.

Wahl is also in favor of creating a centralized system for approving and tracking overtime.

Still, the demand for overtime could grow in the coming years. Wahl said the department is expecting significant attrition over the next two years due to a wave of retirements. If the department can’t hire more officers and shepherd more recruits through the academy, overtime will have to fill the gaps.

Meanwhile, the department has in recent years failed to hit its call response time targets for all but the most urgent calls.

Wahl is hoping to strike a difficult balance — continue to lean on overtime to backfill shifts while trimming the total overtime budget by identifying efficiencies. Wahl recently proposed reducing his department’s overtime budget by nearly $11 million compared to this year’s spending.

Despite calls from City Council members to maintain existing overtime spending levels, the mayor included the proposed cuts in his final proposed budget.