As the school year begins, districts in cities such as Oakland, Fresno and Los Angeles have not gone on a hiring spree.

But they might soon.

California has revamped its school funding formula in ways that will send billions more dollars to districts that educate large numbers of children who are poor, disabled in some way or still learning to speak English.

It's an approach that numerous other states, from New York to Hawaii, have looked into lately. But none has matched the scale of the change now underway in the nation's largest state.

"The trend is toward more and more states providing additional assistance to students with special needs," says Deborah Verstegen, a school finance expert at the University of Nevada, Reno. "California is moving into the forefront with this approach."

It wasn't an easy sell. There was a lot of debate in Sacramento about whether this was a Robin Hood approach, robbing from the rich to give more to the poor.

In the end, however, the old system was so convoluted that no one was willing to defend it.

"The former school finance system had not really been conceptually revised since the early 1970s, when President Reagan was governor of California," says Michael Kirst, president of the California Board of Education. "It had no relationship to student needs."

How It Got That Way

California spends more money on education than other states -- not just because of its size, but because of the complex nature of state and local finances there.

Around the country, a significant share of education dollars still comes from local property taxes. In California, though, the state itself picks up a larger-than-average chunk -- nearly 60 percent of the total K-12 tab.

Traditionally, Sacramento has not only provided the funds but dictated to districts how they spend big parts of their budget. The state sent out money through more than 40 categorical grant programs, which meant that schools had to spend a certain amount of dollars on a wide variety of specific mandates, from anti-tobacco lessons to reducing class sizes for younger kids.

In addition, the complex funding formula led to lots of neighboring districts with similar student populations somehow receiving vastly different amounts of money. The whole thing had become immensely convoluted over time and "could justifiably be called lunatic," wrote the Los Angeles Times editorial board.

Political Payoff?

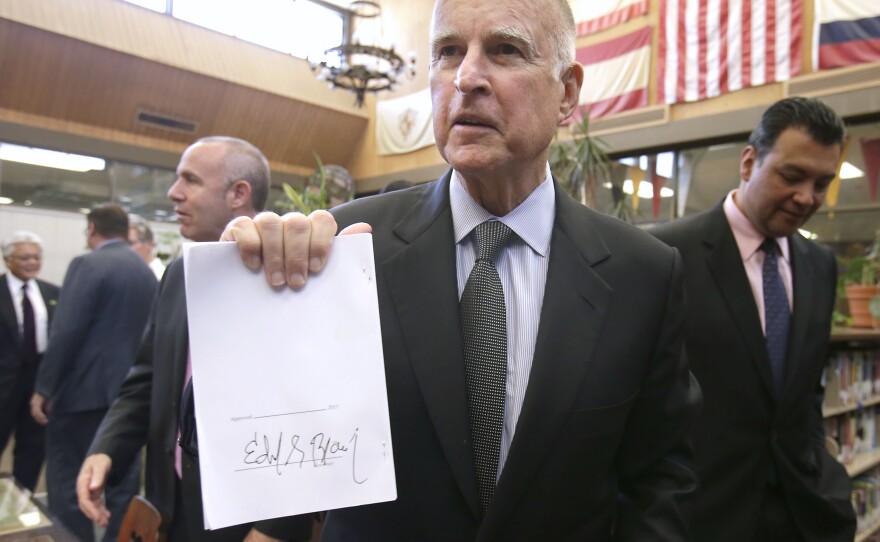

Thanks to a tax increase approved by voters last fall, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown decided both to pump more money into the system and try to make its distribution more rational.

He also wanted the budget to reflect the new realities of the state. Latinos now make up a majority of California schoolchildren, while students of Asian descent are the fastest-growing segment of the school population. Four out of 10 California kids live in homes where English is not spoken.

But investing more in their future meant directing money away from more affluent, suburban districts.

"The rich districts lost out on this," says Thad Kousser, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego. "The new California electorate -- all these Latinos now finally showing up at the polls -- brought Jerry Brown victory. This is the first concrete payoff for that electorate."

Something For Everyone

Brown was able to sell the idea by giving more money to all districts. Still, superintendents in plenty of wealthier districts complain that, with their funding severely cut by the state during the recession, they should be made whole before billions per year get redirected toward poorer quarters.

Even under the old system, districts with lots of disadvantaged kids got more money, but now their budgets will increase in a big way.

"Within most legislators' districts, they had school districts that were both, quote unquote, winners and losers," says Margaret Weston, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California. "It didn't cut along party lines. It had Republican support, as well."

With the new formula, every district will get a certain amount of money per student. In addition, they all will get 20 percent more for each student who is disadvantaged in some way.

The big change comes with what are called concentration grants. Districts where 55 percent or more of the student populations are poor, disabled or English learners will get 50 percent more money than the simple per-student base amount.

What drove that decision? The thinking goes that many students from poor backgrounds face challenges, but schools where they make up the dominant share of the population can be especially challenging.

The law also brings the state's thousand-plus charter schools, many of which serve disadvantaged kids, into the regular school finance formula.

"It aligns state law with the fact that it costs more to educate these students," says Jonathan Kaplan, senior policy analyst with the California Budget Project.

A District-By-District Experiment

The formula change is going to take a long time to kick in -- as long as eight years. The Board of Education is still figuring out the rules for controlling the money.

For the most part, the state will allow districts to spend the money however they see fit -- whether it's on new teachers, iPads, improved transportation systems or better health care. Whatever they believe will improve achievement.

"We will hold them accountable for what their results are," says Kirst, the education board president.

It's all in keeping with a broader set of experiments that Brown is running in the state, shifting greater responsibility onto localities when it comes to prisons, health and welfare programs.

When it comes to education, the funding change will free up districts to experiment in ways that could shed light on what techniques work best for improving performance among students who are traditionally the most difficult to educate.

Policymakers around the country will be watching the results with interest. "Education is the best way to get someone better prepared," says Eric Kearney, a Democratic state senator in Ohio who has sponsored a proposal similar in intent to the California plan. "This is just doing that for poorer kids who are in poorer districts."

The new funding structure will also allow California schools greater flexibility for adapting to the new set of "common core" standards in education that are being implemented across most of the country.

"The consensus opinion is that money does matter, but it matters how you spend it," says Weston of the Public Policy Institute of California. "This will provide some experimental conditions for researchers and economists to look at what strategies and programs actually improve student outcomes."

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.