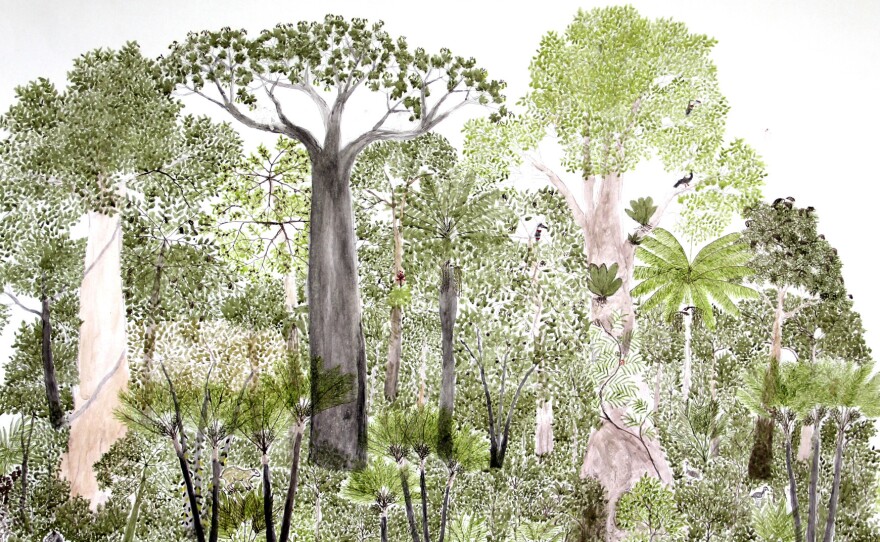

Looking at the painting above, it's easy to imagine the artist spent days, weeks maybe, observing the rainforest to get the details right. Off to the right, a large bird perches on a branch. Turtles and fish swim in the river. Several species of trees reach upward, vying for light through the forest canopy.

The artist painted it all by memory.

But, I am told, he doesn't consider himself an artist.

Nonetheless, the paintings of Abel Rodriguez are on display at the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington D.C., as part of the Waterweavers exhibition, a celebration of Colombian culture. And his work has captured the attention of art dealers and curators, both in Colombia and here in the U.S.

Adriana Ospina, the collections curator, tells me Rodriguez's story as she leads me through the exhibition. He's a member of the Nonuya indigenous people, from the Caqueta River region of Colombia, close to the rainforest, who have been farmers for centuries. "His role in the community is to know the plants," she says. "He's like a teacher." Rodriguez's knowledge, she says, comes from a combination of observation and wisdom passed down from generation to generation.

Rodriguez's intimate understanding of plants of the Amazon caught the attention of a Dutch nonprofit organization called Tropenbos International Colombia. This group works with indigenous people to document their natural and cultural practices. They met Rodriguez in the 1980s and realized he was a repository of a vast amount of lore. He taught the Tropenbos scientists to identify local plants and explained which are eaten and which are used for medicinal purposes. With their help, he even created a stunningly-illustrated book on the plants cultivated by his people.

Unfortunately, many indigenous people, including Rodriguez, were forced to leave the forest in the 1990s due to increasing armed conflict in the area. Now living in Bogota, he continues to mine his lifetime of knowledge of the rainforest to teach others. "I had never drawn before, I barely knew how to write, but I had a whole world in my mind asking me to picture the plants," Rodriguez told a Tropenbos International interviewer in a post on their website. In Bogata, using materials provided by Tropenbos International, Rodriguez began creating paintings and drawings — entirely by memory.

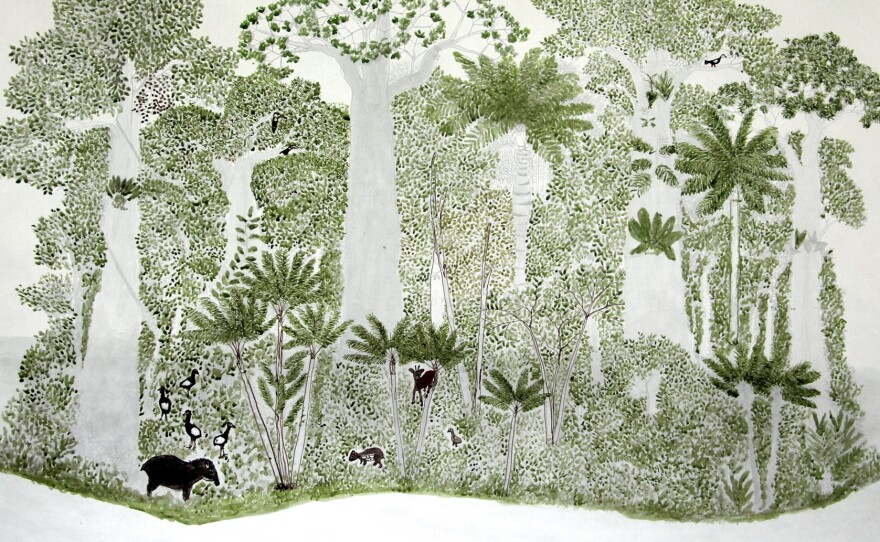

A selection of his works hang on a gallery wall in the Waterweavers exhibition: 12 pieces titled Ciclo anual del bosque de la vega — seasonal changes in the flooded rainforest. The intricately detailed paintings in ink and watercolor are rendered in delicate shades of green and brown, highlighting leaves and shadows. The paintings show how the rainforest changes as the seasons pass.

At first glance, the paintings look similar, but upon closer examination, gradual differences emerge: a tree bursts into leaf; fish and turtles crowd the river and then disappear; the river rises and falls throughout the year.

I tried to interview Rodriguez. It was not meant to be. The complications of translators who understood the local dialect and international group calls couldn't be overcome. So I had to turn to the exhibition's accompanying book, Waterweavers: A Chronicle of Rivers, which includes an interview with Rodriguez, in which he talks about his art via a translator. "I always try to bring out the figures as they should be," he says, "It may not be exact, but it does show how the forest is, and that's the way I've gone on painting."

"But he's not a trained artist," Ospina says. "He didn't want to be an artist." Painting is just something he does. When in the Waterweavers book Rodriguez is asked how he makes his art, he replies, "with my hand."

He seems more eager to describe the subjects of the paintings themselves, which he does with an attention to detail gained from years of careful observation:

"This painting includes the larger trees, such as the marañón and the higuerón, and various seed- and fruit-producing trees eaten by animals, which are painted first. Then come the smaller trees, such as the açai palm, the large guama, a carguero de dormilón, another larger lecythis, the sangre toro, and the bombona and yavarí palms. The small ones give depth to the mountain, in my opinion. When the river is high, these lowlands are flooded, and so all the animals that would usually be here, are now in higher parts. During the summer months (December and January), fish start going up the river because they know that the water is going to rise, and they're looking for the overflows to enjoy the abundance of worms and seeds. When the waters begin to rise, worms are brought out of the ground, and the fish eat them; the other animals begin to migrate further into the forest. The monkeys stay because they like to look at their reflection, as ugly as it is, in the water. They descend along the lower branches and approach the water's edge; and then see that there's another monkey down there. That's how they amuse themselves. That's why, when the river is high, you'll see more monkeys by the river than you will in higher areas."

He's not only a gifted artist but he clearly has literary talents as well.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.