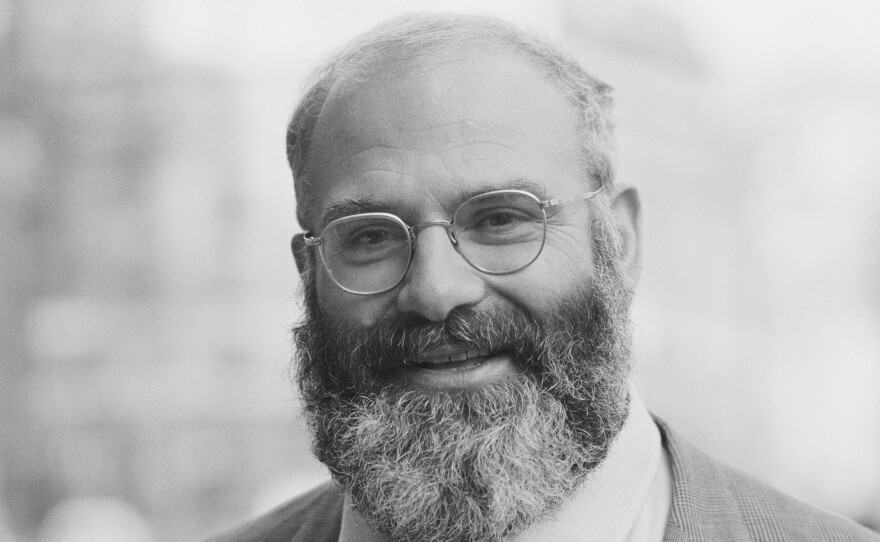

Oliver Sacks, a neurologist and best-selling author who explored the human brain one patient at a time, has died of cancer. He was 82.

Sacks was best known for his books The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Awakenings, which became a 1990 feature film starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro.

Sacks cared for, and wrote about, people with unusual brain disorders that left them catatonic — or haunted by Irish lullabies, or unable to recognize their own spouses. In a 2007 NPR interview, he said, "While I've always wanted to get people's stories, I also like to know what's going on in the brain, and how this wonderful two or three pounds of stuff in the head is able to underlie our imagination, underlie our soul, our individuality."

Sacks' ability to combine science and storytelling eventually led to prestigious academic posts and best-selling books. But his career got off to a rocky start.

"The first part of Oliver's life was a challenge," says Orrin Devinsky, a professor of neurology at New York University, where Sacks worked for many years. "He tried to make it as a scientist and didn't do well."

Sacks was born in London. Both of his parents were doctors, and Sacks himself went to medical school at Oxford. But when results of the final anatomy exam were posted, Sacks saw he had scored near the bottom.

So he went to a local pub. After four or five hard ciders, Sacks headed back to school and asked to take an optional essay exam to compete for the university prize in anatomy. By that time, the exam had already started.

"So Oliver literally staggered into this room with about 15 or 20 students busily writing into their blue books and asked the professor if he could take the essay exam," Devinsky says. "And the professor looked at him kind of like: Are you sure you are in the right place?"

He was. Even though Sacks arrived late and left early, his essay on brain structure and function won the university prize.

Writing would open doors for Sacks his entire life. He told NPR in 2001 that even as a child, he wrote constantly in a journal.

"Rendering into words is absolutely an instinct with me," he said. "I used to be called 'Inky' when I was a boy. I was always sort of covered with ink. I still sort of write my books by hand. I'm not very fond of computers."

Sacks also didn't like cellphones and other devices that he saw as impediments to human interaction. "Oliver was living in the late 19th century in many ways," Devinsky says. "In all the good ways."

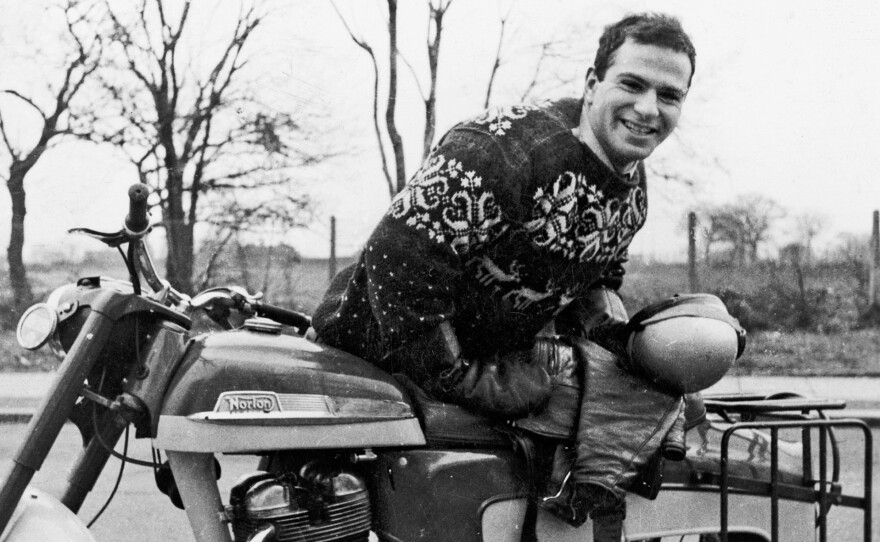

After medical school, Sacks left London for California. There, he completed a residency in neurology and lived a pretty wild life.

In his autobiography, On the Move, Sacks describes having casual sex with men at a YMCA in San Francisco, becoming a body builder at LA's Muscle Beach and using staggering amounts of recreational drugs.

Sacks also liked to risk death while riding his motorcycle through Topanga Canyon. "He would go down the canyon with his eyes closed sometimes," Devinsky says. "He would go through lights sometimes at rapid speed feeling he could make it and dodge all the cars."

In 1965, Sacks moved to New York City, where he focused on writing and medicine. He was known for spending an enormous amount of time with each patient and learning the intimate details of each person's story.

Devinsky says from time to time he would send one of his own patients to Sacks for a consultation. "And then I would get this four-page, five-page, six-page note back with historical features of the person's life, insights into their neurological disorder, fitting pieces together that I'd never even seen the pieces, let alone put them together," Devinsky says.

In 1973, Sacks became a star with the publication of his book Awakenings. It's the story of a group of patients who contracted sleeping sickness and fell into a trancelike state.

The book inspired a play by Harold Pinter and, in 1990, a feature film in which Sacks was played by the late Robin Williams. The two became good friends during the filming, and Williams talked about Sacks while promoting Awakenings on The Tonight Show:

"He's an amazing man," Williams said. "He's about 6 foot 4 inches. He's like a combination of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Albert Schweitzer. And he also looks like Santa Claus, 'cause he's got this big beard. ... And the amazing thing is, as big as he is and as strong as he is, he is this very gentle and compassionate man who is brilliant."

After Awakenings, Sacks would go on to write several best-selling books about people with unusual brains, including An Anthropologist on Mars, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Musicophilia. He also wrote about his own odd brain, which was unable to recognize faces and had to adapt to losing vision on one side when a tumor appeared in his right eye.

Sacks talked about this cancer, a melanoma, in 2010 on Fresh Air. "Although I'm sorry this happened to me and is happening to me, I feel I might as well use it and investigate it and write about it and just speak of myself as I would speak about one of my patients."

In his autobiography, which came out this year, Sacks for the first time revealed many intimate details of his own life: his fraught relationship with his mother, his acid trips and his homosexuality.

In February, Sacks wrote an op-ed in The New York Times announcing that the cancer in his eye had spread to his liver. In the piece, he pledged to spend his remaining days deepening friendships, saying farewell those he loved and writing.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.