If you want to get a sense of the problem, just go to a local hospital emergency room.

On a weekday afternoon at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Hillcrest, Dr. Roneet Lev looked at a computer screen that lists all of the patients in her emergency room.

“We have 55 people in our emergency department," said Lev as she pointed to her computer screen. "And if I forward, I see there’s two people on a psychiatric 5150 hold, a person here with anxiety. If I scroll down, we can see here suicidal, suicidal, suicidal, suicidal, suicidal, suicidal, suicidal.”

In a different part of the ER, Lev stood outside of a room that used to be dedicated to cardiac patients.

“Now we’ve moved them upstairs, and we have four dedicated beds in a locked area where we have psychiatric patients, and they’re there 24/7 with a dedicated psychiatric nurse," Lev said.

This room is full seven days a week, Lev said. Other psychiatric patients are spread throughout the unit.

In the last few years statewide, the number of psychiatric cases in hospital emergency departments has skyrocketed — in some places, one out of five patients has a psychiatric issue.

The increase may be due in part to the Affordable Care Act, which has allowed millions of additional Californians to get Medi-Cal coverage.

Lev points out ERs can handle psychiatric emergencies. But they’re not designed for people who need continuing acute care.

“It’s a chaotic environment," Lev said. "There are lots of distractions. It’s the absolute wrong place for a person who’s psychotic and gets to hear all sorts of voices around them.”

How the mental health care system should operate

Here’s how the mental health system is supposed to work: People with mental illnesses can be treated at community clinics or doctor’s offices.

People in crisis can be stabilized at ERs, and then discharged to psychiatric hospitals or other locked facilities that can provide acute treatment. Some of those patients may still need an extended period of care, for which there are long-term care facilities.

The problem is nearly all of these places that provide supervised treatment for people with severe mental illnesses are full. That includes the county’s psychiatric emergency hospital on Rosecrans Street, and Sharp Mesa Vista Hospital, the largest private provider of psychiatric crisis services.

Mesa Vista’s medical director, Michael Plopper, said the system doesn’t have enough capacity.

“All of these places where we typically send our most seriously mentally ill are impacted," Plopper said. "We’re backing up in the hospital because we can’t find appropriate placements in the community, and then the emergency departments are having difficulty getting patients into our facilities because we don’t have the space.”

Mental Illness By The Numbers

• 1 in 4 adults experiences mental illness in a given year.

• 1 in 17 adults live with a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, major depression or bipolar disorder.

• Approximately 1.1% of American adults – 2.4 million people – live with schizophrenia.

• Approximately 2.6% of American adults – 6.1 million people – live with bipolar disorder.

• Approximately 6.7% of American adults – 14.8 million people – live with major depression.

• Approximately 18.1% of American adults – 42 million people – live with anxiety disorders.

• Approximately 20% of youth ages 13 to 18 experience severe mental disorders in a given year.

188,000 San Diego County residents live with severe mental illness

According to The National Alliance on Mental Illness, about one in 17 Americans has a severe mental illness. That means in San Diego County, more than 188,000 people are living with diseases like schizophrenia or major depression.

Michelle Ahkoi, who lives in South Bay, was diagnosed with severe depression when she was 16. In 2009, after going off her medication, Ahkoi spent a month at Sharp Mesa Vista Hospital.

“When you’re in a manic episode, it’s very intense," Ahkoi said. "I didn’t even know I was bipolar at that time, but I started hallucinating and I was hearing things and seeing things. And I was very delusional.”

Ahkoi was discharged, and soon had another manic episode. She was admitted to another hospital, and diagnosed with a severe condition called schizoaffective disorder.

Ahkoi later wrote a poem about what it felt like:

It’s like polar opposites. North and south pole. It’s too much at once. It’s like an atomic bomb went off, and your thoughts are in a rush. Intensity is insane in the brain. Can’t relax, 'cause your brain is out of wack.

The hospital wanted to send Ahkoi to the county’s long-term care facility in Alpine, but there were no beds available.

Her mom, Mitzi, said watching her daughter languish was horrible.

“Bipolar depression is overwhelming, and there’s a lot of struggles in it," Mitzi Ahkoi said. "And I want the best for her, but you can’t get the help.”

Plopper believes it’s a matter of misplaced priorities.

"I think our most seriously mentally ill have not gotten the attention they need in this county," Plopper said. "And we're suffering the consequences of that."

County's main residential treatment facility

The county's main residential treatment center for people with severe mental illness sits on five acres just off a main road in Alpine.

It has two main buildings that house 113 clients. They stay anywhere from two to three months to two years.

Most of the clients have schizoaffective disorder, said Center Director Kristin Allred.

“They have a tendency to have more symptoms that prevent them from functioning well in the community, and or standing out in the community, responding to voices, agitation," Allred said.

The clients benefit from a highly-structured routine, Allred added.

“It starts at six o’clock in the morning for, whether it be coffee social or getting people up and out of bed and starting to get them engaged in the day," she said. "To breakfast, and then community meetings, onto we have several focus groups that occur throughout the day.”

Clients have 21 group meetings a week. They have activities, outings, and therapy sessions. They take medication, as well.

The goal is to help them understand their illness, and develop the skills to take care of themselves.

Allred said everyone gets better, even those who are severely impaired.

“They don’t all get better to the point that they can care for themselves independently in a home, in the community, and work a full-time job," Allred said. "But everybody improves at some level.”

County adds long-term care beds

Until 2014, Alpine was the county’s only long-term care setting for people with severe mental illnesses.

Last year the county added a 42-bed facility, Crestwood San Diego, to the mix.

Just a few months ago the county also contracted with a 40-bed facility in Chula Vista. Taken together those additional beds represent a 72 percent increase in capacity.

Michael Krelstein, clinical director of the county’s Department of Behavioral Health, believes the new facility should ease the long-term care shortage. But he said the mental health system has other components, including acute care and outpatient clinical services.

"It’s tempting to think that there’s one magical answer, or special go-to resource that if we just had more of it, everything would be fine," Krelstein said. "But really, it’s from a systems perspective more complicated than that.”

Krelstein said his department is constantly struggling with how best to spend its money.

“How much of those resources should be community-based and early intervention and education?" Krelstein asked. "How many of those resources should be preserved for helping those who are struggling the most with frequent homelessness and food insecurity and trauma?”

Program seeks to prevent severe mental illness

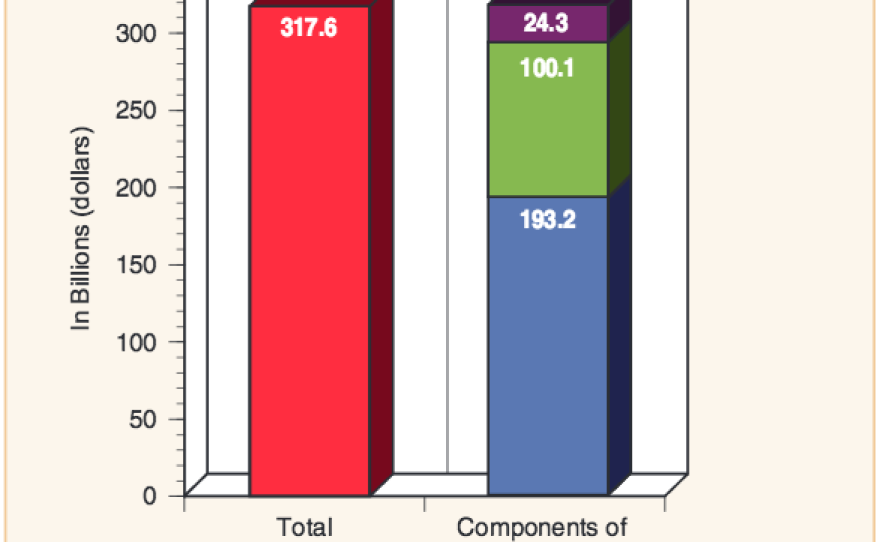

The costs associated with severe mental illnesses are estimated to be more than $300 billion a year in the U.S.

Research shows early intervention after the first signs of a serious mental illness can make a difference.

That's the idea behind a unique program in San Diego called Kickstart.

At a recent group meeting in Kickstart's main offices on Mission Gorge Road, assistant director Joseph Edwards called the gathering of clients and their parents to order.

“Well, I figure for the sake of time, if you guys don’t mind, even while you’re finishing up your pizza, we can maybe start the check-in," Edwards said.

Edwards grabbed a marker and started writing on a board. He asked each person in the room two questions.

“So, what has been going well for you over the last couple of weeks?” And “What could be improved over the next couple of weeks?”

One by one, clients and their parents answered the questions, and Edwards wrote the responses down in two columns.

After everyone chimed in, Edwards jumped to the next order of business.

“So, at this point, as you all know, we’re going to look at the list of issues on the right, and pick one that we can focus on for the rest of the group tonight," Edwards said.

This group meeting with clients and their parents is a key component of Kickstart.

The program seeks out young people ages 10 to 25 who’ve experienced some early signs of psychosis, like hallucinations or delusions.

Kickstart gives them individual counseling, group sessions and other activities to help them gain problem solving and coping skills. In time, clients get an understanding of their condition, and learn to manage it.

Edwards said the goal is to prevent clients from developing a serious disease.

“Psychotic mental illness can be the most destructive, and costly," Edwards said. "So to prevent that, I think, is very helpful to the community.”

Millionaires' tax

In 2004, California voters approved Proposition 63, also known as the Mental Health Services Act. It's a 1 percent tax on millionaires, with the proceeds used to create a special fund for mental health services. San Diego County has about $172 million it can spend on certain types of initiatives, including early intervention programs.

All of Kickstart’s services are free with participants going through a screening process before being admitted to the program. The program gets its funding from the County Health and Human Services Agency and the county's portion of the money from the Mental Health Services Act.

Reducing stigma

Thomas McKnight, one of Kickstart’s therapists, said most of his clients feel burdened by the stigma of having a mental illness. McKnight likes to address that head on.

“I talk to a lot of my clients, and they say 'Nobody understands what I’m going through,'" McKnight said. "And it’s really good, and it can be really powerful, to bring family members in and allow them to hear their client’s story, and then talk about stigma.”

Kickstart tries to reduce stigma in other ways, too.

Recovery is possible

On a Friday afternoon at a park in Mission Valley, a number of clients drew elaborate, multi-colored chalk drawings on a sidewalk.

Peer support specialist Ian Adye grabbed some chalk and joined in. He leads some of these group activities, and also spends some separate one-on-one time with clients, just doing things that they like to do.

Adye knows what it’s like to struggle with a mental illness. That’s because he’s a former Kickstart client himself.

“Everyone has mental struggles," Adye said. "Everyone has things they go through. Just because your struggle is specific, and people don’t understand it, that doesn’t mean anything about you as a person. And I think my image can kind of represent that in a way.”

Ayde is one of nearly 500 young people that have gone through Kickstart since it began five years ago. Most clients finish the program in about 18 months.

Kickstart officials said in 2014, 75 percent of their clients showed clinical improvement. And 84 percent saw their overall functioning stabilize or get better.

Ayde said he’s living proof that people who grapple with mental illness shouldn’t give up hope.

“If you continue to fight, if you continue to push yourself, you build the skills, you do the work, you will get better," he said.