During the time Army Captain Charles Gail wandered Okinawa with his box camera in 1952, his intention was artistic. But his slice-of-life photos — along with his detailed notes about each scene — serve as precious documentation of a way of life that’s gone now.

So when UC Santa Cruz was offered a trove of photos that Gail took while stationed on Okinawa, History Professor Alan Christy jumped on it. Then, he took 15 students on a couple of international field trips to the island, to research and write history themselves.

“By working with me on the research,” he said, “they’ll learn how history is done.”

Much of Okinawa’s historical record destroyed

The epic battle on Okinawa, depicted in this 1945 newsreel, was devastating. About 90,000 soldiers were killed on both sides. More than 110,000 Okinawans died.

After World War II, the US military moved in and established several bases, whether the Okinawans wanted them or not. Civilian photography was restricted. Christy explains, “WWII in Okinawa was immensely destructive of the heritage landscape: archives, images, not to mention, of course, people.”

As part of Christy’s project, UC Santa Cruz students were asked to seek out the exact places where Gail shot his photos, and found some of the people he photographed are still alive, or at least remembered by people alive today.

“Crowds would gather around the photo — all the old folk, particularly, because these are photos from 70 years ago — and argue about where this photo was or wasn’t,” Christy said.

“‘Ah, I remember those people, the people were were selling fish like that.’ You’d just get these great conversations and sit there and soak it in,” Christy said.

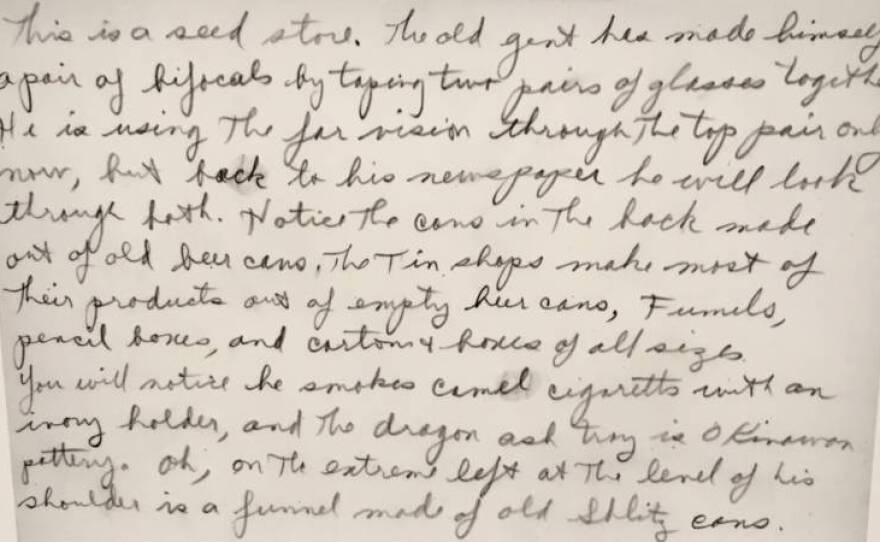

Gail focused his camera on long-suffering peasants carrying goods to market, fishermen hauling their catch onto the beach, and adorable children everywhere.

Now, a selection of his photos, as well as photos shot by students in the same locations, are on display at the Mary Porter Sesnon Art Gallery at UC Santa Cruz.

‘The Gail Project: An Okinawan-American Dialogue,’ which includes 50 digital prints reprinted from the original 200 black and white photos, is being developed into a traveling exhibition.

The current exhibit also includes an online archive, with oral histories from Americans and Okinawans, as well as undergraduate research and writing.

No “us” and “them” when the subjects are your relatives

Among the student historians: Alexyss “Lex” McClellan, who’s majoring in history and critical race and ethnic studies. McClellan is also part Okinawan.

“Most of my family’s worldly possessions were destroyed during the battle, so photos are rare,” McClellan said. Her grandmother married an American serviceman and moved to San Diego.

“This project has been a blessing to me because it’s given me an opportunity — to talk to my grandmother, her sisters, her brother and the rest of my family on a level they empathize deeply with — and so for them to tell stories that I had never heard growing up,” McClellan said.

McClellan and her family are also enjoying an upwelling of pride at the attention UC Santa Cruz is paying to Okinawan culture. Outside of Japan, many people are not aware the islanders don’t consider themselves Japanese. Their neighbors to the north only took over Okinawa in 1609.

Okinawans speak different languages. Or rather, they did. After years of Japanese and American occupation, less than 10,000 people now speak some form of Okinawan. It’s just another way a distinctive indigenous culture fades into history.

McLellan said Gail wasn’t thinking about history when he took his photographs. “He was just taking pictures he thought other Americans might find anomalous or interesting. But to us, these are a gold mine.”

For Geri Gail, a former employee of UC Santa Cruz who always knew her dad was a talent, it’s a thrill to see his pictures archived in excellent company alongside prominent 20th century photographers in the university’s growing collection.

“It just gives me goose bumps. I’m so proud,” she said, looking at her father’s photos up on the wall at the Sesnon Gallery.