Influential Chicana artist and activist Yolanda M. López passed away Sept. 3, 2021 at the age of 79. Born and raised in San Diego's Barrio Logan neighborhood, she returned to study at UC San Diego in the 1970s, well into her emergence as an artist and grassroots organizer in the Bay Area.

The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego will open a retrospective of López's work — her first solo exhibition — October 16, 2021, which will be on view, for free, through April 24, 2022. Additionally, artist Katie Ruiz will create an ofrenda in the San Diego Botanic Garden beginning Oct. 23. SDBG will announce more details in the coming days.

KPBS asked several writers, activists, artists and administrators to reflect on the impact of López — whether on the art world, politics, or their own work. Here are their words:

Leticia Gomez Franco

Executive director, Balboa Art Conservation Center

La Virgen de Guadalupe is said to have first appeared in the hills of Tepeyac to Juan Diego in 1531. 447 years would pass before a young, bold, brave and unapologetic Yolanda López, paintbrushes in hand, would reclaim her as ours. To say that Yolanda’s work has been impactful is an understatement. Her work completely broke through the Chicano cultural canon, forging a path forward for Chicana feminist theory, a path, Chicana’s like myself continue to travel on. I can’t think of any work that has had such a gargantuan effect on culture as hers, that has invited us to reimagine, reinvent, and reclaim so much for ourselves as women. Since then, an army of empowered Chicanas have reclaimed so much more, and throughout her life, Yolanda had been there as a gentle but persistent guiding and supportive force for us. She was passionate about access, about art and culture belonging to and with the people. So in her absence, we forge on, running shoes on our feet and serpents in hand, to continue reclaiming it all.

Alessandra Moctezuma

Curator, professor of fine art and Chicana studies, gallery director at San Diego Mesa College

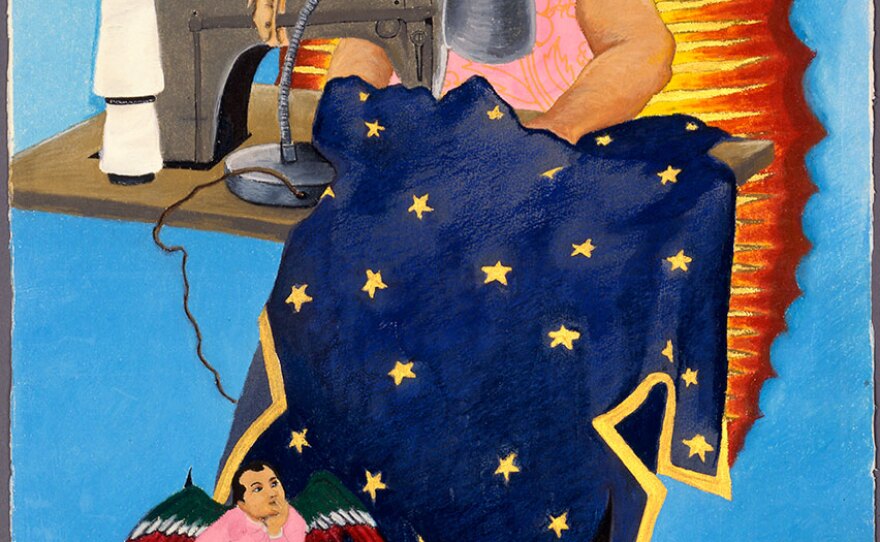

Yolanda López's “Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe” became a symbol of Chicana women’s liberation. In a rebellious adaptation of the Mexican patron saint, the artist paints herself in athletic gear, brandishing and crushing a snake in her hand, and stepping over the cupid. Done in 1978, this work captured the rise of feminism, women who challenged patriarchal tradition to march at the beat of their own drum. López was the first of her family to go to college and in the series of three paintings she also pays homage to the women that came before her, mother and grandmother, who nurtured and supported her dreams with their love and labor.

Besides being an artist López was also an ardent activist. In another important image, “Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?" she appropriates the famous WWI draft poster but replaces Uncle Sam with a fierce Aztec warrior crushing a set of immigration plans. A San Diegan from Shelltown, she was keenly aware of the painful discrimination, exploitation and abuse targeted at immigrants and Mexican-Americans who are the indigenous natives of this land. López forged a balance between being artist, mother, activist; her personal life and art were intertwined with the struggles of her community. In her running shoes and adorned with a divine halo, she paved the way for us.

Kathryn Kanjo

David C. Copley director and CEO, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

It is a special honor, here in the artist’s hometown, to present the first solo museum exhibition of this lauded figure in the worlds of art and activism. As a crucial component of the exhibition, many of López’s commanding drawings received essential conservation treatments, allowing, at last, for the public display of these formative artworks. The outsize portraits of the artist, her mother, and her grandmother will be a revelation for many visitors.

Rachael Ortiz

President, Barrio Station

I met and organized with Yolanda in San Francisco over the San Francisco State "College" protest that took hundreds of us in paddy wagons to City Prison in San Francisco. We overcame all the court nonsense and won the ethnic studies, women's studies, etc. at SFSC. Yolanda was highly respected in San Francisco and the entire Bay Area. Then running into her here in San Diego, we had so much to reminisce, and yes, she was a real change maker and an incredible artist and Latina lady who I will hold in my heart forever. I wish her blessings of peaceful rest in her new journey. Yolanda López Presente!

Griselda Rosas

Artist

Yolanda López's art honored the history of Mexicans in this country, dignified and altered the media representation of Chicano/a/x - employing visual poetry, humor and poignant political/activist art. Religious and colonial imagery was an essential element in Yolanda’s work as well; she changed the patriarchal-mother symbol of La Virgen de Guadalupe into a sign of female empowerment and hope.

In various forms, for me her work is a direct extension of my life and culture; the image of Yolanda López mother in a sewing machine as La Virgen de Guadalupe is profound and mimics part of my heritage. For instance, all women in my family created extraordinary things on the sewing machine, all were devotees of La Virgen, all immigrants, and all hard working females.

In 2019, before the pandemic, I was invited by Jill Dawsey to have a solo show at the museum in an exhibition adjacent to the retrospective of Yolanda López – I felt so honored and content. However, the pandemic put everything on hold. Although my exhibition was cancelled, Yolanda López’s exhibition is still part of the Feminist Art Coalition and the Museum of Contemporary Art honors and will continue to tribute the most important Chicana artist of the twentieth century after she sadly left this material world.

Despite López's legacy and contributions to the arts she never had a solo museum exhibition until Dawsey approached her in 2019. It is sad to think that Yolanda López struggled financially most of her life, despite her contributions to the arts and to the history of Chicano/a/x community, however recently before her departure she received the Latinx Artist Fellowship, a $50,000 prize underwritten by the Andrew W. Mellon and Ford foundations at the age of 78.

Rita Sanchez

Author of "Chicana Tributes," retired professor of Chicana studies

Yolanda López proved to be a breakthrough artist during a time of enduring male camaraderie in the arts in the 1970s. López […] spoke of the exclusion she felt, when, as an accomplished artist, she went uninvited by the men, the San Diego Chicano Park artists. She painted under the Coronado Bridge anyway, with a group of young girls who called themselves Mujeres Muralistas, after the San Francisco artists. Her actions influenced others to give back to their community, providing service to youth. She influenced women who felt those feelings of exclusion too, and so she gave them hope as her words and actions spoke for many. Her work on La Virgen de Guadalupe Series became highly visible to her San Diego local community and the rest of the world. San Diego now boasted a master artist and she was a woman.

Through Yolanda's work and journey, I was able to introduce my students to the power of women, what a woman could do if she dared, and if she accepted the encouragement offered to them by Yolanda and others.

As for the controversy she stirred in the arts, Yolanda López did what art was meant to do, to create debate and dialogue, to instigate new thought, to challenge antiquated thinking. Yolanda brought forth one of the most sacred icons in Mexican life, religion and culture. She did not denigrate the image. She questioned the ongoing male interpretation of women's saints. Women were expected to behave as men defined them. And that was not easy, nor even possible. Students began to see how Yolanda's work expressed how women had more to consider in their spirituality than passive obedience and silence, but deliberate joy, energy, intelligence, and action.

Claudia Cano

Artist

Yolanda López was an artist who celebrated Latina women. When I think of her, I think about how she decided to break boundaries and stereotypes by portraying the resilience of brown women and bringing them out from the shadows of their everyday roles to a state of recognition, respect, and reverence.

Leticia Hernández-Linares

Author of "Mucha Muchacha, Too Much Girl," lecturer at San Francisco State University.

Yolanda López was an inspiration and so beloved by so many in the neighborhood and the Bay and of course beyond. I wasn't close with Yolanda, but we had a special relationship that is becoming more and more rare in this barrio. Yolanda López was my vecina. Before COVID, I would see her walking by often, and we would exchange greetings — another rare thing as so many strangers move in and out and not only don't greet you, don't see you. During COVID we shared groceries, and we looked out for her. She brought my boys and I some very specific gifts one day, as she was going through her things: an old school theater novel for the musical theater teenager; Chinese Checkers and watercolors for the young artist; a small chapbook of poems by giants such as Gloría Anzaldúa for me. She was funny and tough, and so blunt. May she rest in power.

William Moreno

Former director, the Mexican Museum in San Francisco

I was fortunate to know Yolanda personally - she was an uncompromising force of nature and an inspiration to those who looked to her images for ground-breaking originality. She was a role model of the first order.

Jill Dawsey

Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

Yolanda López was born and raised here in Barrio Logan in San Diego. She was baptized at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, which is so fitting, given that her major contributions to art history revolved around the Guadalupe series.

Her work was always about her own community. She's an artist who worked outside the gallery system for the entirety of her career. And that was in part by choice and in part because the institutional art world has really neglected artists who came out of the Chicano civil rights movement, but also especially the women of that era. We're having her first solo Museum exhibition, but that shouldn't be the measure of her influence. "Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe" is one of the most reproduced artworks in the history of Chicanx art and one of the most written about works. There's so much written about this work, and so its influence is really just pretty astounding.