Sunday, July 27, 2025 at 11 p.m. on KPBS 2 / Stream now with KPBS Passport!

When Black neighborhoods in scores of cities erupted in violence during the summer of 1967, President Lyndon Johnson appointed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders—informally known as the Kerner Commission—to answer three questions: What happened? Why did it happen? And what could be done to prevent it from happening again?

The bi-partisan commission’s final report, issued in March of 1968, would offer a shockingly unvarnished assessment of American race relations—a verdict so politically explosive that Johnson not only refused to acknowledge it publicly, but even to thank the commissioners for their service. AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The Riot Report" explores this pivotal moment in the nation’s history and the fraught social dynamics that simultaneously spurred the commission’s investigation and doomed its findings to political oblivion.

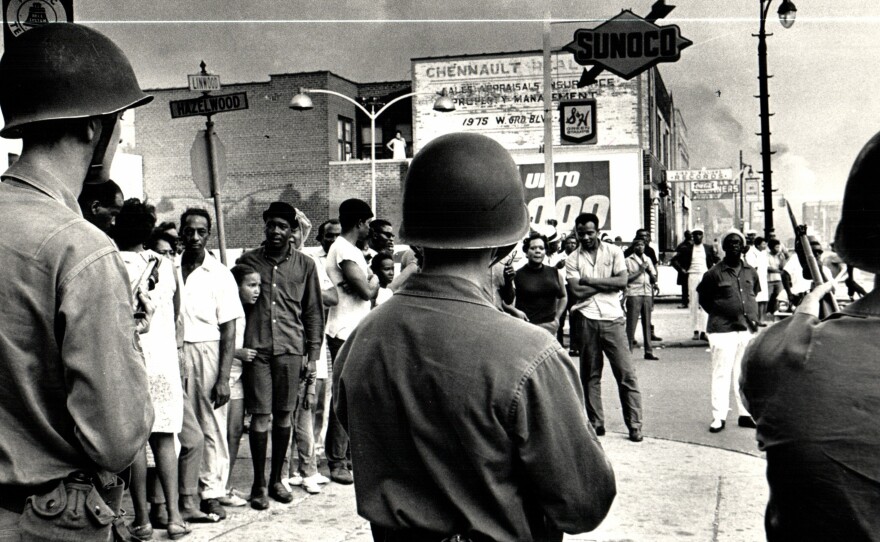

“The simple fact is this: We are in the worst crisis we have known since the Civil War,” said a television journalist in September 1967. Several weeks before, a police raid on an after-hours club in a predominantly Black section of Detroit had sparked racial unrest unlike anything Americans had ever seen: a furious uprising that paralyzed the city, left 43 people dead and burned hundreds of buildings to the ground. Nor was it an isolated incident. The disturbance in Detroit had been preceded that summer by violence in Newark, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Rochester, Toledo, and scores of other cities, mainly in the North and Midwest.

Few contemporary observers expected the bi-partisan Kerner Commission (named after its chair, Governor Otto Kerner Jr. of Illinois) to deliver meaningful answers. Only two members of the commission were Black and both, like the nine white members, had been chosen by Johnson on the strength of their allegiance to him.

Adding to the skepticism was the widespread perception that such commissions were typically convened as a gesture without commitment to any particular course. Johnson, for his part, hoped the commissioners would find evidence of outside agitation—ideally, by Communist-aligned advocates of Black Power—and would draw conclusions that both acknowledged his significant civil rights achievements and shored up support for his ambitious social agenda.

But the Kerner Commission defied expectations. In addition to holding pro forma hearings with experts, the commissioners toured many of the afflicted cities, an experience that moved Tex Thornton, arguably the commission’s most conservative member, “about ninety degrees to the left,” he said. Those visits were followed by thorough field investigations conducted in 23 cities by teams of social scientists.

In the end, although the commissioners split over many issues, there was unanimous consensus for the report’s central conclusion: the cause of urban disorder was white racism—and the spark that set it off was almost invariably police brutality.

Hurried into print, the 708-page report instantly became a New York Times bestseller, with more than 700,000 copies sold in two weeks. CBS and NBC aired documentaries inspired by the book, and millions watched as Marlon Brando read excerpts aloud on the late-night talk show circuit. The urgency of the report’s message was further underscored mere weeks after its publication when Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated and the nation’s inner cities erupted once more.

Yet, according to a poll later that same month, a majority of white Americans rejected the commission’s conclusions and its recommendations. By the time Richard Nixon's law-and-order campaign won him the presidency that fall, the Kerner Commission had been swept from national consciousness. In diagnosing a crisis that Americans then elected to ignore, however, the so-called “Riot Report” was destined to endure. Its findings remain tragically relevant and a dramatic, timely reminder of both the persistence of American racism and the limits of American liberalism.

RELATED: 5 Times U.S. Presidential Commissions Rocked the Country

Watch On Your Schedule: AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The Riot Report is available to stream with KPBS Passport, a benefit for members supporting KPBS at $60 or more yearly, using your computer, smartphone, tablet, Roku, AppleTV, Amazon Fire or Chromecast. Learn how to activate your benefit now.

The film will also be available for streaming with closed captioning in English and Spanish.

Credits: Directed by Michelle Ferrari, co-written by Ferrari and New Yorker journalist Jelani Cobb, and executive produced by Cameo George. Distributed internationally by PBS International