Martin Scorsese's "Killers of the Flower Moon" arrives in theaters and chronicles the Osage Murders, which took place in 1920s Oklahoma.

In 2017, David Grann, a staff writer at The New Yorker, wrote "Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the F.B.I." He constructed it as a true crime whodunit interweaving the Osage murders as symbolic of America's relationship with Native Americans with a look at how the fledgling Federal Bureau of Investigations handled the case.

NOTE: There are spoilers ahead, but the story is all based on a history that is already known, but with which many may be unfamiliar.

After the Osage discovered oil on their land in the 1890s, they were considered the richest people per capita in the world. That led to a sinister series of killings that became known as "The Reign of Terror." The murders were committed by greedy whites trying to take control of the oil. Since the book was structured like a murder mystery, you don't initially know the identity of the killers.

When Scorsese adapted the book, he decided on some significant changes. He came to the conclusion that he did not want the film to be about a lot of white men, so he mostly dispenses with the second part of the book's subtitle and does not focus on the birth of the FBI. Instead, he reframes the story to place the romance between Mollie (Lily Gladstone), an Osage woman with oil rights, and Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio), a white World War I veteran. Scorsese then uses their relationship to reflect the way the United States betrayed the Osage Nation and, on a larger scale, Native Americans.

Scorsese also chooses to reveal almost immediately that Ernest and his uncle William Hale (Robert De Niro) are the murderous villains of the story. On a certain level, that hurts the tension of the film since we know who is behind the plot to kill Mollie and her family from almost the beginning. It is also problematic because we clearly see who is evil and it makes it difficult to understand how Mollie and others can be so blind. If Scorsese and De Niro could have played their hand closer to their vest, then I think the audience might have been lulled into that sense of trust and security that Mollie and her community felt about Hale.

The other key problem is that DiCaprio’s dour performance as Ernest left me unconvinced that he could woo and win Mollie. DiCaprio assumes an almost permanently downturned mouth, and his jowls are seemingly stuffed with cotton like Marlon Brando doing his audition for "The Godfather." DiCaprio's Ernest appears neither charming nor loving, and not even physically attractive. He also seems to possess zero redeeming qualities.

As played by Gladstone, Mollie seems far too smart to fall for the dim-witted Ernest. Every scene they have together, I kept waiting for her to come to her senses and to at some point condemn him for his actions.

Even though the film focuses on Mollie, it’s not really her perspective. She exists in an almost entirely reactive role and she even disappears for a good chunk of the film’s 206 minutes. And, while the film does a respectful job of depicting the Osage culture and brings attention to these horrific crimes, it’s still an outsider’s point of view. I feel like if it were an Osage perspective, there might be more outrage and anger at these injustices.

Scorsese also chooses an odd ending for his film. He closes with a radio play depicting the murders and the FBI's investigation of the case. Scorsese obviously takes delight in portraying the details of a live radio play, but the humor of it seems to trivialize the horrors we have been witnessed. I understand that his point is how America trivialized the murders. The radio play has a white actor putting on a horrible "Indian" accent, and the zippy wrap-up to the play points to the fact that no one was really held accountable for the crimes. Scorsese himself even comes out on stage to deliver the capper, a reading of an obituary in which the murders are entirely overlooked.

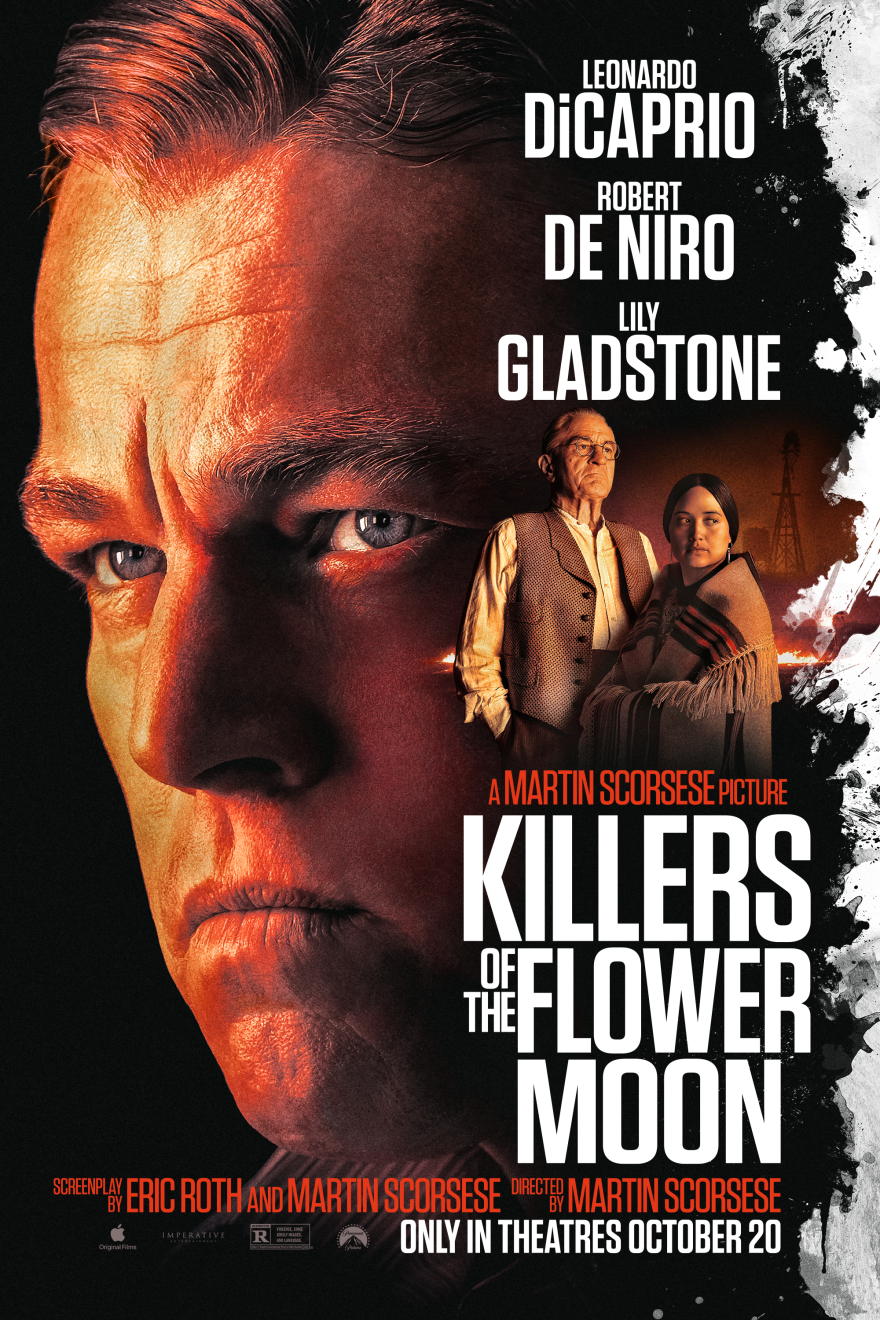

On paper this makes sense, but in the film it feels like the wrong emotional choice. I wanted to end on Mollie and her processing of all the horrendous and criminal things done to her family rather than on white insensitivity, which is well understood. Even the poster for the film gives us DiCaprio's huge face with Mollie much smaller in what is visually a supporting role.

At the premiere for "Killers of the Flower Moon," Hollywood Reporter asked Osage language consultant Christopher Cote, an Osage himself, for his opinion on the film's perspective: "Martin Scorsese not being Osage, I think he did a great job representing our people. But this history is being told almost from the perspective of Ernest Burkhart. And they kind of give him this conscience and they kind of depict that there's love. But when somebody conspires to murder your entire family, that's not love. That's beyond abuse."

Because the injustices and violence depicted in the film have yet to be avenged, I wanted Mollie to have the last word in the film, not Scorsese.

But the film still has merits. I am glad that someone with Scorsese's influence has highlighted this story. The mere fact that he has adapted the book will get people and the media talking about the Osage murders and the Reign of Terror. And that is a very good thing. As always, Scorsese displays a masterful sense of craft and elicits phenomenal performances from Gladstone and De Niro. And, although much has been made of the film's three-hour-plus length, it never really drags.

The film also boasts a stunning score by the late Robbie Robertson. It pounds a steady, solemn beat like a heart thumping with increased intensity. His score rarely serves up predictable punctuation but instead drives the story with a relentless underscore.

"Killers of the Flower Moon" feels epic and sweeping. It stirs outrage and asks us to look at a brutal moment in history. But I just wish the magnificent Gladstone and her Mollie had been given full centerstage.

I also highly recommend checking out this article from The Hollywood Reporter about a fascinating bit of cinema history involving a silent film version of the Osage murders made by the industry's first Native American director.