There's one moment that stands out for Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego curator Jill Dawsey when it comes to the relationship between visual art and disability.

In 2014, she encountered a sculpture by artist Park McArthur that made her breath catch. The sculpture, "Blue Snowflake Commode," is made from a metal stand that evokes a hospital IV drip. A pair of torn pajama pants — their blue snowflake print evoking hospital gown fabric — hang from the stand.

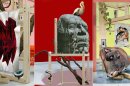

[Artist image description: A pair of torn pajama pants hang from a metal stand. Another sculpture made of a single loading dock bumper titled Passive Vibration Isolation is bolted to a white wall behind the pajamas. A radiator painted white can also be seen behind the pajama sculpture which stands on grey and black checkered flooring.]

"The reason the pajamas are worn and frayed is because the artist's family and friends help her into and out of her clothes and into and out of bed every evening," Dawsey said.

The piece hit Dawsey at a pivotal time in her life, shortly after learning of her own disability.

"I was just so struck and amazed that an artist was making work around these very personal issues."--Jill Dawsey

"I was just so struck and amazed that an artist was making work around these very personal issues. It was eye-opening to me, and it was not long after I had been diagnosed with my own disability. So it really kind of shifted my perspective," Dawsey said.

McArthur's "Blue Snowflake Commode" is part of the "For Dear Life" exhibit opening this month at Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. It's part of a major initiative from the Getty, "PST ART: Art and Science Collide." It's also the first major museum exhibit to survey issues of disability and health in American art in this period.

"For Dear Life" goes decade-by-decade, beginning with the 1960s and the disability rights movement that has its roots in California. The exhibit tackles stigma, medicine and medical authority, activism, epidemics like HIV/AIDS and breast cancer, substance use, caretaking and more. And in the 2010s, McArthur (who is a 2024 Guggenheim fellow) and other significant American artists like Simone Leigh revolutionized the conversation around disability and expression. The period of time covered by the exhibit spans to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when disability awareness and activism experienced another significant transformation.

Niki de Saint Phalle and 'moving westward' for health

San Diego has long been considered a hub for medical science and biotechnology — and Dawsey said that the county's adjacency to the medical tourism hub in Tijuana sets the region as a revelatory backdrop for an exhibition about medicine in art.

She also pointed out that historically, many artists have moved westward for health reasons — and this phenomenon also wrote part of her own history.

"My own grandfather moved here from the South to San Diego because of a couple different health conditions, one of which I inherited. So as a third-generation San Diegan, the fact that I'm even here was motivated by health conditions."

"For Dear Life" studies how health intervenes in life and art — including those geographical changes.

For example, French artist Niki de Saint Phalle moved to San Diego's coastal desert climate towards the end of her life to ease rheumatoid arthritis and lung problems from the toxic materials she'd long used to sculpt.

!["La Peste," a 1986 mixed media work by Niki de Saint Phalle: A series of cartoonish skulls frame the left half of a colorful wall relief, which is dominated by a red reptilian monster that anthropomorphizes La Peste [the plague] of the title. On the composition's right side, human faces frame flowers, a sun and moon, and a hand, or Hamsa symbol, that floats at the apex of a mountain.](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/4d79bbc/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1000x616+0+9/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fkpbs-brightspot.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com%2F2b%2F7e%2F1cf5746343edbcd8b7fd06284579%2Fniki-de-saint-phalle-la-peste.jpg)

'Reductive lenses'

Artist identity and biography can be "reductive lenses" for art, Dawsey said. Defining an artist by their disability is problematic — something that the curators wanted to keep in mind for a project like "For Dear Life." Often, the connection to disability, illness, medicine or art is just one component of complex art.

"All of us exceed or sometimes are misaligned with the labels that are placed on us, so I think many queer and disabled people resist disclosing their identities. Even many artists in our exhibition don't specifically name what kind of disability they have. It's really not so much about autobiography as it is about the personal," Dawsey said.

She also said that popular culture has a tendency to talk about artists and disability through the lens of "overcoming" or "triumphing" over their conditions, which is not something they were interested in doing with this exhibit.

"Illness and disability is something each of us experience throughout our lives or will eventually experience. In many ways, what we all share is our bodily vulnerability."--Jill Dawsey

"We use the term disabled or disability in a really broad and inclusive way to suggest affinities between a wide range of conditions, and to think about the fact that illness and disability is something each of us experience throughout our lives or will eventually experience," Dawsey said. "In many ways, what we all share is our bodily vulnerability."

Recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) suggest that one in four Americans identifies as living with disability.

"It is such a prevalent experience in our culture, and it's one that isn't talked about enough," Dawsey said.

Accessibility: 'I always want more places to sit down'

Working on this project has also helped her understand her role as a curator in making museums accessible for more people.

"I know when I go to museums, I always want more places to sit down," Dawsey said.

So, the museum added chairs. Chairs that are also works of art, of course, but they're meant to be used.

Other accessibility considerations include audio descriptions, large print labels, captions and transcripts for all video works, American Sign Language interpretations for public programs, improved directional signage in the museum, and a new "calm room" for respite from sensory overload.

'Hold on for dear life'

Dawsey said that one of the things she'll take away from her work on this exhibit is the idea of leaning on others and depending on community and relationships of care. In fact, interdependence is where the exhibition's title was born, in the expression "Hold on for dear life."

"We all have this notion of individualism, or the bootstraps mentality of American culture. We sort of imagine we do things on our own, and then when we really think about it, we're all dependent on others. And consciously bringing that to mind, that the ways in which life itself is a collaboration, always, as is making an exhibition and art itself. The advisory group who I've been in dialogue with, that's one of the nicest outcomes, is feeling like there is this community here," Dawsey said.

The museum worked with an advisory committee made up of local artists, curators, educators and advocates who are living with disabilities or are caregivers.

The group includes Amanda Cachia, Alexia Arani, Bhavna Mehta, Tatiana Ortiz-Rubio, Elizabeth Rooklidge and Akiko Surai.

A spin off exhibition, "Picturing Health," opens at Best Practice gallery in Bread and Salt in November. Some of the contemporary, local artists included in that show are Philip Brun Del Re, Maria Mathioudakis, and artists from the advisory committee: Mehta, Ortiz-Rubio, Surai and curator Rooklidge.

"For me, one of the most important things to have emerged from the show is this community around art and disability here in San Diego. We are not the only ones who are doing this kind of work," Dawsey said.

A public concern in the public sphere

For Dawsey, connection and accessibility come from speaking out.

"It's really important, I think, to position disability in relationship to a public culture, because it's something that so often used to be kept in the private sphere. It was seen as a private concern. Even just the vulnerability of me talking here about these issues in the public context, but I think it's really important to look at community and to think about the ways that we are all interdependent and rely on one another," Dawsey said.

Those frayed pajama pants come to mind.

Despite being nervous about speaking out about her own experience with disability and chronic illness, Dawsey pointed to a quote from the memoir of artist and HIV/AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz, who has work in the exhibit:

"Each public disclosure of private reality becomes something of a magnet that can attract others with a similar frame of reference," he wrote.

"For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability"

On view Sept. 19, 2024 through Feb. 2, 2025.

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, 700 Prospect St., La Jolla.

Free public opening with tours and exhibition film screenings: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 19.