Zoila López holds a bottle of turbid water toward a window above her kitchen sink, swirling its contents as sediments turn the water murky brown. It came from her tap.

It's a hectic morning in her Sonora, Mexico home, as her three children, ages three to seven, help to make her husband's lunch. López’s middle son, Jesus, 6, fills a cup of purified water from a five-gallon container in the kitchen to help wash vegetables. They don't think the tap water is safe.

“This is what comes out, especially in the morning,” said López, 32, as she again swirled the water bottle. “We’re using purified water for everything now — and that I can’t even trust.”

López and her family are among thousands of people impacted by a 2014 mine spill that polluted the Sonora River. It's been called one of the worst environmental disasters in Mexico's history and has threatened the livelihood of the Sonora River Basin residents.

Frustrated by what they claim was a slow response from the Mexico government and a lack of transparency from the mine, the people of the region are pushing back. More than 600 residents, including the López family, are part of a movement demanding that officials do more to restore safety to their health, and that of the lands they call home.

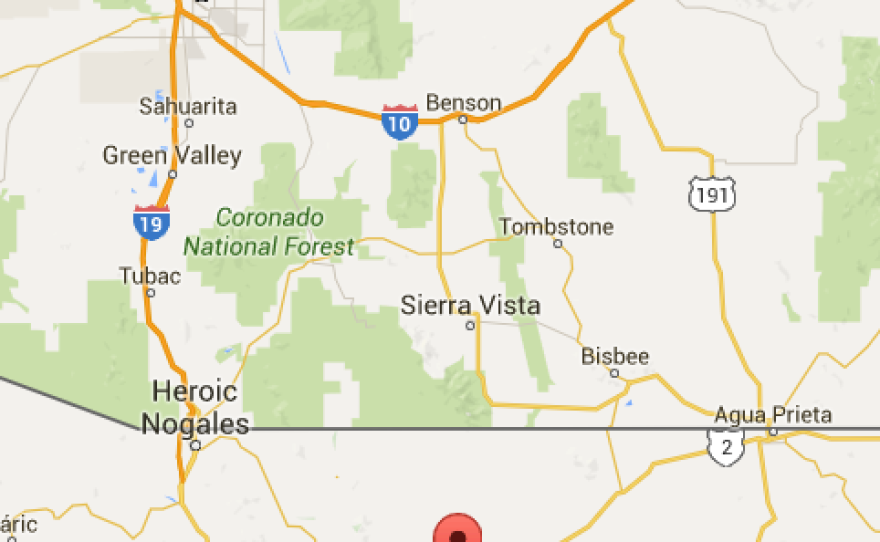

On Aug. 6, 2014, nearly 11 million gallons of a copper sulfate acid solution poured into the Bacanuchi and Sonora Rivers from the Buenavista del Cobre copper mine, which is owned by Grupo México. The spill impacted an area almost 200 miles along the Sonora River Basin, which is home to more than 22,000 people.

It's been more than a year since the spill and officials from both the mine and Mexican government claim the river is now safe. An environmental remediation plan was submitted by the mine and approved by Mexican environmental officials. But cleanup efforts have only reached about 19 miles from the site of the spill, which only encompasses land owned by Grupo México.

“We can’t say that it’s been 100 percent remediated. The remediation plan is for 5 years,” said Adolfo Garcia Morales, then a Sonora delegate to the Mexico Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB).

The 2014 spill happened just 25 miles from Arizona, south of its border with Mexico in the northern state of Sonora.

The Sonora River, which flows from the city of Cananea to near the state's capital, Hermosillo, is considered the agricultural and ranching lifeblood of the region.

López’s husband, Armando Enríquez, lost his harvest when the government temporarily closed all of the Sonora River water wells after the spill. The impact to his farms got worse when Hurricane Odile hit Mexico one month later, causing the river to overflow its banks and inundate his lands with toxic water.

"Despite the fact that it impacted us economically, it caused a lot of harm to ranching (in the region)," said Enríquez, 35. "Everything that I have is here, this is how I make a living."

Federal authorities in Mexico reached an agreement with Grupo México to establish a $150 million trust fund to offer financial reparations to ranchers and other businesses impacted by the spill. As of August 2015, the fund had disbursed more than 36,000 individual claims, some of which included multiple claims per person and vary from health to business reimbursements.

Enríquez received the equivalent of $7,000 to offset his business losses, but he said his farming expenses are four times that amount. He said this is in addition to the fact that immediately following the spill, his wife and children started to have health problems.

“At first we thought we were safe because Grupo México brought us water in jugs and trucks. But after consuming that water we started to have health problems,” López said.

Grupo México distributed more than 45 million liters of clean water during the first month after the spill, according to statements made by the company. But the mine and Cofepris, the Mexican agency that oversees public health, didn't respond to repeated questions about where the water came from or how its safety was assessed.

The Mexican government said it immediately dispatched mobile clinics to the region to monitor its residents for heavy metal exposure. But López claims the doctors wouldn't test her blood for toxins, a test her family couldn't afford on their own.

Seven months later and after she made her case public, López was contacted by government health officials. It was then that López and her family were tested for heavy metals. Their cases are recognized among more than 300 others with health problems tied directly to the spill.

They are now receiving treatment at a government-run epidemiology treatment center that opened in March 2015.

Community questions mining oversight

Grupo México, a Mexican-owned mining conglomerate with sites in Latin America and the U.S., failed to immediately notify federal authorities about the spill, as is required by law.

Profepa, the federal agency that has oversight over mine operations, determined that the company was operating illegally on a site under construction.

“It was a combination between a construction accident and an improper decision from the mine to start using facilities that were not ready for the production process,” said Arturo Rodriguez Abitia, a deputy director of industrial inspection for Profepa.

Abitia said a pipe broke in a leaching pond, which is an area used in the copper extraction process, and that the mine didn't have the necessary containment dam to prevent the chemicals from flowing downstream.

Grupo México was fined almost $1.5 million for more than 50 violations identified by Mexico’s federal Department of Environmental Protection (Profepa). A separate criminal investigation continues.

Grupo México did not respond to repeated emails and phone calls for comment on this story.

“The company had been operating with negligence and the government oversight was absent,” said attorney Luis Miguel Cano of PODER, a citizen advocacy group for corporate accountability in Latin America. “It wasn’t an accident. It wasn’t an act from nature. It was an incident that happened in a permissive environment.”

But Abitia, the industrial inspection representative from the Mexican government, argues that the government couldn't effectively regulate the mine because it wasn't aware of the construction project.

“Authorities are not responsible; we were in no condition to inspect those facilities since they were officially not operating,” Abitia said. “They didn’t inform authorities that they began working there.”

More than 600 residents along the river, including Armando Enríquez and his family, formed the Rio Sonora Basin Committees, uniting the communities that live along the river. With help from PODER, the group has filed the equivalent of seven class action suits against Grupo México and the Mexican government.

The goal of the lawsuits are to hold the government and the mine more accountable. Under one provision, known as “amparo,” the groups are trying to sue the mine on the grounds that it has violated human rights.

In response to one of the lawsuits, a district judge in Sonora ordered Conagua, the federal agency responsible for monitoring water quality in Mexico, to re-test dozens of wells near the river. Conagua didn't respond to requests for comments about the October 2015 ruling.

In the meantime, farmers such as Armando Enríquez are uncertain when the cleanup efforts will reach their land.

“Those people who say that everything is going well, they should come and milk a cow every day. They say it’s clean? They should come and drink a glass of milk from those cows," Enríquez said. "We drink it because we have no other choice.”