When Heather Woock was in her late 20s, she started researching her family history. As part of the project she spit into a tube and sent it to Ancestry, a consumer DNA testing service. Then in 2017, she started getting messages about the results from people who said they could be half-siblings.

"I immediately called my mom and said, 'Mom, is it possible that I have random siblings out there somewhere?'" Woock says. She remembers her mom responded, "No, why? That's ridiculous."

But the messages continued, and some of them mentioned an Indianapolis fertility practice that she knew her mom had consulted with when she had trouble conceiving.

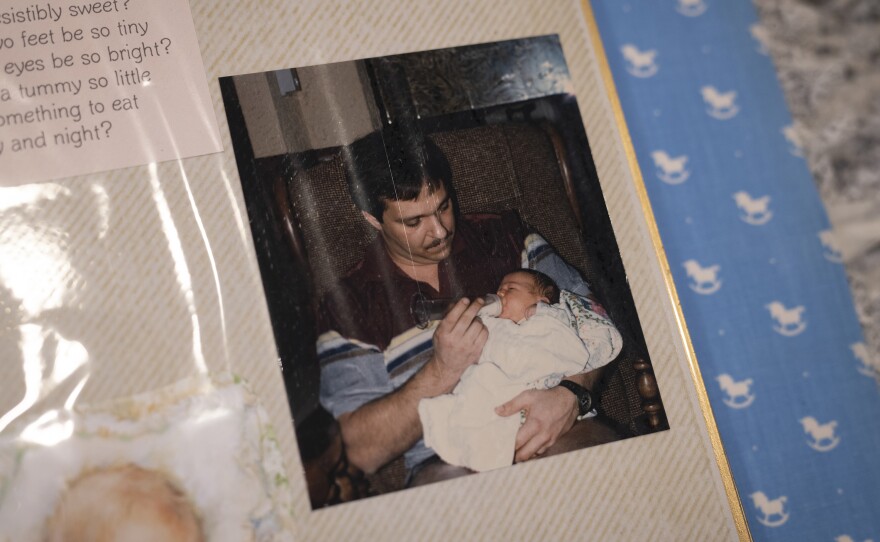

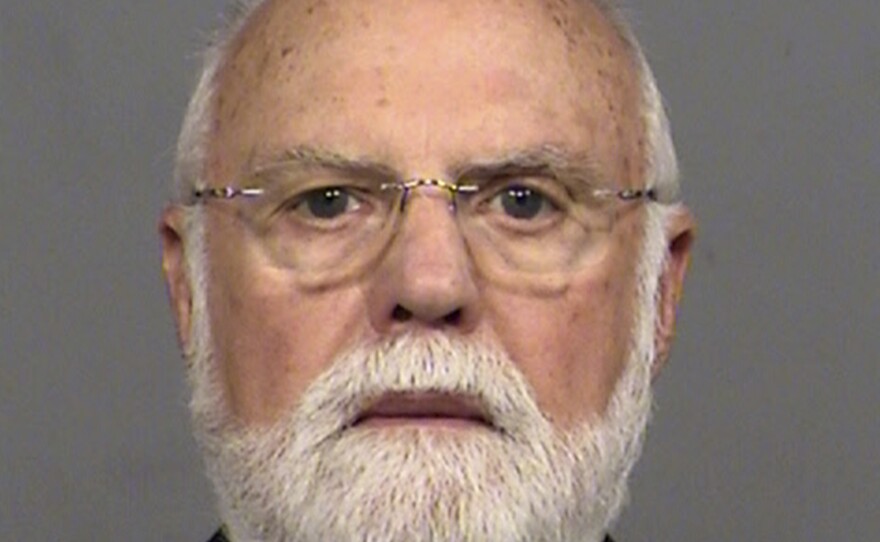

Woock did some research and finally learned the truth. Donald Cline, the fertility doctor her mother saw in 1985, is her biological father.

"I went through an identity crisis," she says. "I couldn't look in the mirror and think about, Where did my eyes come from? Where did my hair color come from? I didn't even want to think about any of that."

Woock hadn't known that her mom used artificial insemination to conceive her and neither of them knew the doctor had used his own sperm.

"We now know Cline used his own sample and squirted it into my mom," Woock says.

In the 1970s and 80s, Cline deceived dozens of patients and used his own sperm to impregnate them. He has more than 60 biological children — and counting.

For Woock, as the story of her parentage sunk in, it was distressing for another reason: She wanted to start her own family and was having trouble conceiving. And now she needed to turn to the fertility industry that had so badly betrayed her mom.

"We were doing all of the calendaring ... everything that is out there to help you get pregnant, we were doing that," Woock recalls.

But after six months, when she still wasn't pregnant at 32, she went to a fertility clinic for some tests.

"I had to fill out all this paperwork, and there's a slot that says kind of like, 'Is there anything else you'd like to share?' " Woock says.

Yes, there most certainly was.

Fertility treatment today

New allegations of doctors using their own sperm keep coming to light — thanks to genetic testing like Ancestry revealing networks of half-siblings — in states like Idaho, Ohio, Colorado, and Arkansas.

But those doctors performed artificial inseminations decades ago. Could what happened to Woock's mom happen in a modern fertility clinic?

Dr. Bob Colver, a fertility specialist in Carmel, Ind., says it's a question many of his patients have asked. But he says it's unlikely. These days, there are more people involved in the process, and in vitro fertilization happens in a lab, not an exam room.

"Unless you're in a small clinic where there's absolutely no checks and balances, I can't even imagine that today," Colver says.

It's now illegal in Indiana, Texas and California for a doctor to use his own sperm to impregnate his patients. But there's no national law criminalizing what's called "fertility fraud."

Fertility medicine has advanced a lot since the 1980s, but women trying to get pregnant today with the help of medicine face a baffling array of treatment options that can be hard to navigate and can be hugely expensive. And some critics say the growing, multi-billion dollar fertility industry needs more regulation.

For example, sperm banks may not get accurate medical histories from their donors, who could pass along genetic diseases. And there's no limit on how many times a donor's sperm can be used, which some donor children worry could increase the chance of inbreeding. Sperm donation guidelines from organizations like the American Society for Reproductive Medicine are voluntary. There was a contestant on "The Bachelorette" last year who said his sperm helped father more than 100 kids.

Unrealistic expectations

When Woock decided to get her first fertility treatment, she set some preconditions with the clinic. She insisted on having a female doctor and insisted that doctor be in the room for all appointments and would oversee everything that happened.

Her experience with her clinic was very different from mother's with Cline, but nonetheless there were some surprises along the way.

The clinic told her that her problems conceiving could be because of husband Rob's low sperm count and motility (meaning his sperm weren't great swimmers.) They advised a form of in vitro fertilization that involved injecting one sperm directly into one of her eggs in a petri dish.

When doctors told Woock she needed IVF, she felt pretty optimistic.

"I'm thinking going into this that our chances of success are 70, 75%" Woock says.

Fertility treatment can be really expensive, and patients may start treatment with unrealistic expectations. That's because success rates are complicated, and some clinics use only the best numbers in their advertising.

For example clinics can advertise high fertilization rates. But a 70% fertilization rate doesn't mean 70% of eggs turn into babies – plenty can go wrong after the lab combines egg and sperm.

Success depends on your age, your clinic, and the type of procedure you need. But most of the time, assisted reproduction procedures such as IVF don't work. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which tracks assisted reproduction rates in the U.S., reports only about 24% of attempts result in a baby.

'Add-on' technology — and prices

When Woock started her first IVF cycle, she gave herself shots, a couple a day, to stimulate her ovaries to get multiple eggs ready at once. Multiple eggs means more chances for fertilization.

But the drugs have side effects. They gave her headaches, and made her moody and less patient.

"I was actually allergic to one of the medications, which just means that you keep taking it and deal with the itching and rash," Woock says.

But she hung on until it was time for a doctor to surgically retrieve her eggs, at which point patients can face even more choices. Because the couple's fertility problem appeared to be with Rob's sperm, the clinic offered to use a special device to help pick the best sperm for IVF.

"We were kind of like yeah, 'Why wouldn't you?'" Woock says. "If it's gonna give us a better chance, do it."

A device like that is called an add-on. Add-ons are often new technology, described as cutting edge, which can appeal to patients. Examples of add-ons include genetic testing for chromosomal abnormality in embryos — which some specialists argue improve the odds of live birth — and assisted hatching and endometrial scratching, both methods claiming to facilitate implantation.

Jack Wilkinson, a bio-statistician at the University of Manchester, researches add ons, which he has found can increase costs — and, he says, they may not work.

"We quite often see there's no benefit at all," Wilkinson says. "Or, possibly even worse, that there's a disadvantage of using that treatment."

Wilkinson says the device Woock's clinic offered could work, but the evidence supporting it is thin.

Failed fertilizations

The clinic called Woock the morning after her egg retrieval. None of Woock's eggs fertilized. The procedure revealed that her husband's sperm quality wasn't the only fertility issue the couple faced.

"They immediately saw that there was something wrong with my eggs," Woock says. "My eggs are just total crap."

She underwent a second round of IVF with the same result – no fertilization.

"Getting that news the second time ... felt even more set in stone that this was going to be a very long, challenging road," Woock says.

Challenging and expensive. Most states, including Indiana, don't require insurers to cover fertility treatment. Without insurance, a round of IVF can cost more than $10,000, even more than $20,000, with no guarantee the patient will get pregnant.

Woock was lucky that her employer-provided insurance covered a lot. But it still wasn't cheap. She had to pay for some medications, "plus, you have to pay lab and facility fees that insurance doesn't pay," Woock says.

Donor sperm and eggs aren't generally covered, either. Those can be tens of thousands of dollars.

Woock faced a hard choice: After two failed attempts, did she want a kid enough to go through IVF again?

She and her husband decided they did. So Woock did a third round of IVF. And then a fourth. When that didn't work, she gave up on using her own eggs.

"What I expected as I was growing up and picturing my children is not what I will see," Woock says.

Woock and her husband decided to try donor eggs. If all goes according to plan, she could still carry a child. She wants to keep trying.

"I realize that pregnancy is incredibly challenging on your body and your mental state," she says. "If I can make it through a year of IVF, I can make it through morning sickness."

This story is part of a partnership between NPR, Kaiser Health News, and the podcast, Sick. You can hear more about the doctor who used his own sperm on Sick's first season. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and go to sickpodcast.org for more information.

Copyright 2023 Side Effects Public Media. To see more, visit Side Effects Public Media. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))