Cultural life in Iraq is reeling after years of attacks linked to the violence that has gripped the country since the U.S. invasion in 2003. Although much has been lost with the targeting of cultural icons and institutions, people interested in books, music and art are still finding ways to breathe life into Iraq's intellectual community.

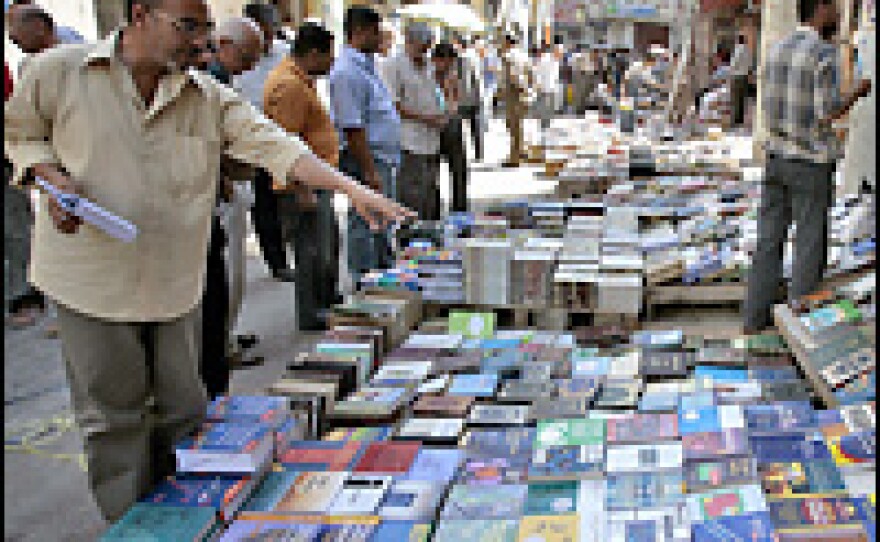

The most visible recent attack was a bombing this month at the booksellers market on al-Mutanabi street in Baghdad.

The street was home to booksellers and cafes where intellectuals would gather. It was a bustling market where people could flee the everyday violence of Iraq and talk about art, literature and life.

Then a car bomb exploded in the midst of the market, turning an intellectual oasis into a desert of blackened buildings and burned books. It wasn't the first attack on the market. But it was the deadliest, killing more than100 people.

Down a nearby alley is the mourning tent for the people who died on Mutanabi Street that day.

Salim al-Kushalli lost his five brothers when the bomb ripped through the family's printing shop.

"Of course, we were expecting Mutanabi street to be targeted one day," Kushalli said. "Because anyone targeting Mutanabi street is targeting Iraq's civilization. He targets Iraq's history. He targets Iraq's heritage."

As he talks, people come to kiss Kushalli on the cheek and express their condolences. He is mourning his family. But he says he is also grieving the loss of something intangible.

"This funeral is not only for the individuals who were killed, but also for all the culture that is gone without being documented," he said. "There are one-of-a-kind books that are gone, manuscripts gone. They were not cataloged. They were something personal and important. But now everything has been lost in the fire."

Just up the road, near the backhoe that is removing debris, is an old man sitting in a plastic chair. He's held vigil for the past week, waiting for his son to be found under the rubble. He was a student who came to buy a book on the day of the attack. His body has not yet been discovered.

"Please help me to leave the Baghdad. OK?" the man said. "I want leave Baghdad because my son and my house ... I do not have anything here OK?"

After four years of conflict, it is the familiar litany of tragedy in Iraq.

But against all odds, an institution that collects books and documents is being rebuilt just down the road. It's the Iraq National Library and Archive.

The library is literally rising from the ashes and being turned into something that goes far beyond what it was before.

Saad Eskander is the head of the National Library. When he took it over in late 2003 it had been looted and burned, a few plastic chairs were all that remained.

Now it's a spotless hive of activity which he's proud to show off. One room is filled with state-of-the-art computer systems.

"You see all of the people here ... are young. It was part of my policy here to employ them and produce new blood," Eskander said. "Because I do believe that new technology needs young brains, new brains."

In the library's restoration department, workers have been trained in the Czech Republic and in Italy. Other fully staffed and equipped areas include a facility for transferring documents to microfilm, a cataloging operation and a department that hunts down documents for the collection from Iraqi government ministries.

Four hundred people work at the National Library, trying to preserve fragments of Iraq's past. It seems almost utopian for today's Iraq. But reality does intrude.

Eskander points to a bullet hole in a window. The library resides in one of the most dangerous areas in Baghdad, near Haifa street. Five of the staff have been killed. The library has had to close for days at a time due to heavy fighting in the neighborhood.

But that is outside. Inside, Eskander has rules to keep the problems of wider Iraq at bay.

"First, I prevented any political activities within the national library and archive. I removed all the pictures of certain politicians and religious men," Eskander said. "I prevented any sectarian joke to be told in this institution, and I think we succeeded. We didn't have a single sectarian problem."

Many women are department heads.

"Now we have a woman's society in the National Library, and even they celebrated the woman's day last week," he said.

The library is a meritocracy, with promotions through peer votes. In most state institutions political and religious affiliations lead to jobs and promotions.

For Eskander, the National Library and Archive is more than just a building. He says it's a battlefield where the prize is Iraq's very soul.

"Institutions like us, [the] book market like al-Muttanabi, they are [an] important source of uniting and unifying the country," Eskander said. "[The violence] is not just a political attack on Iraq, it's a cultural attack as well."

Eskander acknowledges there have been setbacks at the library, and says he's received threats. But he says will never leave Iraq.

"If all of us emigrate, they will win the war and they will take the country," Eskander said. "So, as a citizen of this country, it is my duty to resist and fight them in my sphere. And my sphere is culture.

What Eskander has done at the National Library hasn't effected life outside his walls, yet. But in a place that so often lacks hope, his library seems like a small beacon of light in the dark.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))