In Germany, opposition to nuclear power runs deep. But that appears to be changing.

Eight years ago, anti-nuclear sentiment was so strong that the government passed a law to phase out nuclear power completely. Today, soaring energy prices and concerns about global warming are making the German people think again.

Anti-Nuclear Activism

Longtime activist Karsten Hinrichsen has devoted nearly three decades to the anti-nuclear fight. He erected a wind turbine in his village of Brokdorf, near Germany's North Sea coast — and says it generates enough power for about 300 of the village's 1,000 residents.

He says Germany needs more renewable sources of energy like these and that the country needs to shut down the fenced compound located some 300 yards away — the Brokdorf nuclear power station.

"If there will be a big accident, we have to leave this country," Hinrichsen says. "Maybe you get cancer, too. But for many, many generations, this land cannot be used by persons because it's wasted."

In 2000, it appeared Hinrichsen's efforts had paid off — the government agreed on a plan to phase out Germany's nuclear plants by 2021.

But just eight years after the phase-out law was enacted, German attitudes about atomic energy are shifting and politicians are increasingly calling for the phase-out law to be overturned.

That would shatter Hinrichsen's dreams of a nuclear-free Germany.

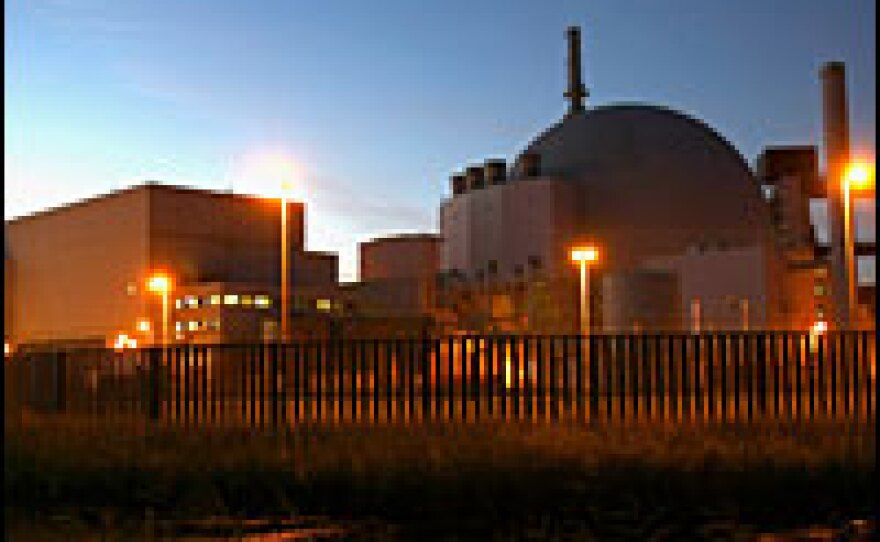

The Brokdorf Reactor

The Brokdorf plant was once the site of Germany's biggest anti-nuclear demonstrations. But now, plant officials say, only a handful of protesters show up about once a month.

Dieter Marx, the director of an atomic energy industry group, says Germans are still more suspicious of nuclear power than are most other Europeans. But, he says, new concerns about rising energy costs are changing minds.

"For years, even decades, we've had a very emotional debate," Marx says. "But now the debate is centered on the facts. Nuclear power is a very cheap form of energy, and people these days are complaining about high prices. Nuclear power also ensures we have a secure energy supply."

In a recent survey, 54 percent of Germans wanted to allow nuclear power plants to operate longer than the phase-out law foresees. That is up from 40 percent just six months ago.

The trend is likely to continue as Russia becomes more and more assertive, as Russia is a big energy supplier for Germany and the climate is playing a role.

Jeanne Rubner, who wrote a book on energy in Germany, says the anti-nuclear movement has been largely based on worries about radiation harming the environment. That concern is being pushed aside by another ecological danger: angst.

"It seems like our society needs something to be afraid of," Rubner says. "It has been nuclear for a long time. If we project our fears on climate change, then nuclear will be more or less OK."

A new German attitude toward nuclear power would put the country in line with other large industrialized nations. France gets almost 80 percent of its electricity from nuclear. Finland is building a fifth reactor, and at a summit of G8 leaders this summer, Germany's nuclear exit plans left it isolated.

Back in Brokdorf, Eggert Block says he's glad opinions are changing. He was the mayor for 38 years and says he never understood German opposition to atomic energy. The nuclear power plant next door hasn't worried most Brokdorf residents, he says. In fact, he adds, many consider it a savior.

"This whole area [used to be] the poorhouse of this state," Block says. "Then the nuclear power plant came to Brokdorf and clearly helped our economy. It's provided jobs for the whole region. It was a good thing then and is a good thing now."

Block points to the large skating rink down the road that revenue from the power plant made possible. Its roof is covered with solar panels, which he says shows Germany is still committed to developing renewable energy sources. But nuclear provides more than a fifth of Germany's electricity, and Block says that means the country simply can't afford to shut down its reactors now.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))