Even the entrance to Yu Bo's restaurant, like so much else about it, confounds expectations. It's a nondescript doorway into a gray apartment block, through which you are whisked into a hot, hectic kitchen.

A courtyard garden, replete with a tiny pagoda, a minuscule goldfish-filled pond and a clump of bamboo trees, sits on the other side.

That sense of astonishment at this miniature hidden garden blossomed and intensified throughout our extraordinary marathon meal of experimental Chinese cuisine in Chengdu, the capital of southwestern Sichuan province.

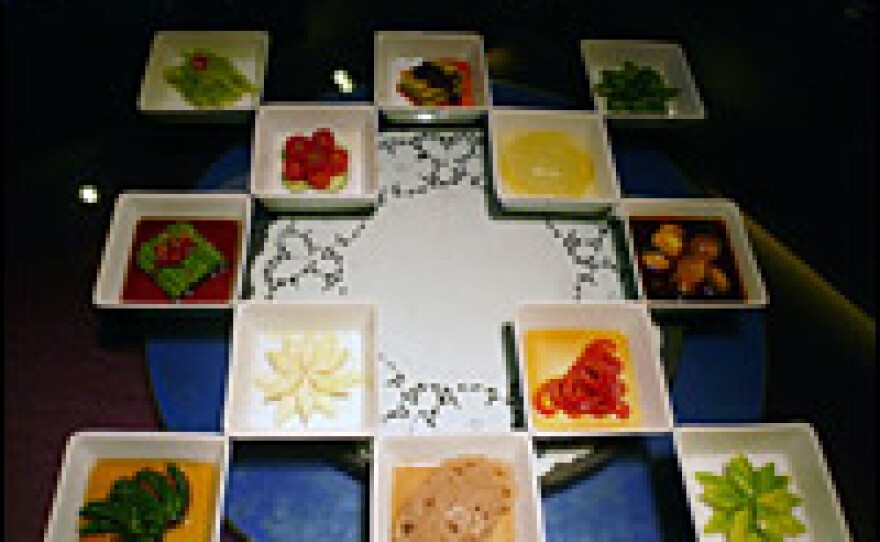

Our table was already laid with 12 tiny starters, including plaited Chinese chives, squares of lemon aloe jelly and quail eggs in chili and soy sauce.

From that moment on, dishes arrived at the table at a gallop: piquant pigeon-breast floss; traditional red-braised pork chunks served in blue-and-white china; blowfish from the Yangtze River; a disc of omelet balancing a truffle gilded with gold leaf; dumplings made from wafer-thin cabbage leaves; typical street food — chunks of chillied rice-jelly — topped with the highest of all high-end delicacies, abalone.

This restaurant takes its food seriously. This meal is a communion, with conversation interrupted frequently as the waitress explains each dish.

Presentation is key: Some dishes are culinary works of art with a touch of humor. Yam croquettes filled with double-cooked pork masqueraded as pipa fruits (also known as loquats) against cucumber-carved leaves.

One classic Chengdu dish, tea-smoked duck, is presented as delicate paper-thin slices hanging from a scaffold, to be enfolded in soft bread pockets. And Chef Yu Bo's signature dish — so lifelike one can hardly bear to eat it — is a Chinese calligraphy brush. Its tip is flaky pastry with minced beef filling to be dipped into a tomato "ink."

There's no menu; we are at the mercy of Chef Yu Bo. As with all Chinese banquets, there are some dishes that are challenging, if not downright alarming. Soft-shelled turtle makes an appearance and then, to our surprise, one of the most innocuous-looking dishes turns out to be the most obscure. It was a jadeite-colored steamed egg tinted with spinach, topped with tiny, almost jewel-like transparent clouds, balancing a wolfberry. After much discussion with the waitress, the consensus at our table was these little pockets of blubber constituted some part of a frog's reproductive system.

I later consulted Chinese food expert Fuchsia Dunlop, an enthusiastic fan of the restaurant, who subsequently turned to two food encyclopedias. It turned out to be hashima, sometimes euphemistically known as snow jelly, which is actually the fat surrounding the ovaries and fallopian tubes of the Heilongjiang snow frog. While the thought of eating frog's ovarian fat was off-putting to say the least, the taste was actually inoffensive to the point of blandness.

And still on and on the dishes kept coming. Finally at dish No. 34, we ground to a halt after a white watermelon dessert inspired by the inventive molecular gastronomy of the Spanish restaurant El Bulli and its chef, Ferran Adria.

Chef Yu Bo is in his 40s and trained in a state-owned restaurant, learning traditional Sichuan cuisine for 10 years. In 1995, he began experimenting, not always to popular acclaim.

"Lots and lots of people don't like my food," he told us, mournfully, "especially Chinese people. They say it's not spicy enough, not mouth-numbing enough, not oily enough."

And he worries about the future.

"China's food culture is over," he pronounced. "There's no talent nowadays. Young people just don't value the skills and discipline to cook."

Its future may be uncertain, but for now, China's food culture is most certainly alive and kicking at Yu's Family Kitchen.

Yu's Family Kitchen — No. 43 Zhai Xiang Zi, Xia Tong Ren Road, Chengdu, China. Telephone: 86-28-8669-1975. Price depends on number of people: Between 200 yuan to 600 yuan per head ($30 to $88).

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))