As Secretary of State Hillary Clinton travels to Mexico this week, high on her agenda is the Mexican drug war that threatens to destabilize parts of the U.S.-Mexico border.

The drug war killed more than 6,000 people last year and has prompted some security analysts to warn that Mexico is in danger of becoming a failed state.

The drug war is affecting communities on both sides of the border.

Tourist Haven's Dark Side

Zihuatanejo markets itself as a tropical paradise on Mexico's west coast. Five-star hotels line a crescent-moon-shaped cove. Lean coconut trees sway over clean, soft sand. The currents of the Pacific keep the bay pleasantly warm, attracting Canadians and New Yorkers throughout North America's coldest winter months.

But this small resort also has a dark side. It sits on one of Mexico's primary cocaine-trafficking corridors.

In the past month, heavily armed commandos have attacked the local police with assault rifles and grenades. Five officers have been killed.

After repeated attacks, the entire police force went on strike.

Herman Ramirez Vasillo, who has been with the force for 11 years, says the killings of his co-workers were frightening. And he says a lot of officers quit.

"Roughly 20 officers quit out of fear for their lives," he says.

Now the Zihuatanejo police station looks like a military garrison in a war zone. The complex is surrounded with sandbags, and officers with high-caliber rifles are stationed in pillboxes out front.

Violence Across The Country

What's happening in Zihuatanejo is also unfolding all across the country. In December 2006, when President Felipe Calderon took office, he sent tens of thousands of soldiers and federal police to confront Mexico's powerful drug cartels.

The cartels responded brutally. A few months ago, the heads of eight soldiers and a former police chief were found in plastic bags just north of Zihuatanejo. Major gun battles, at times lasting for hours, have erupted from the Guatemalan border to the interior highlands to the Chihuahua desert.

Jorge Chabat, a security expert at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics in Mexico City, says Calderon's strategy is to try to pulverize the Mexican drug cartels.

"To transform these four or five big organizations, criminal organizations, into dozens of small cartels. Similar to what happened in Colombia," he says.

The Mexican cartels have come to dominate global cocaine trafficking. Mexico also has become the world's largest exporter of marijuana. Estimates of the revenue generated by the Mexican drug cartels range from $18 billion to $40 billion a year. They use their cash to bribe local public officials and purchase arsenals of military-style weapons. They fund minor league baseball teams and church construction projects.

Chabat says shutting down the drug trafficking business entirely is impossible.

"You are trying to fight the invisible hand of the market with the long arm of the law," he says. "And, historically, the invisible hand wins."

He says the best Calderon can hope for is to diminish the immense power of the nation's largest cartels.

Mexico's top representative to Interpol, the police chief of Cancun, the current holder of the Miss Sinaloa beauty pageant title, the mayor of Ixtapaluca and Calderon's former drug czar have all been arrested recently on suspicion of ties to organized crime. Calderon's former drug czar is accused of being on a $450,000 a month retainer to pass information to the Sinaloa cartel.

Many Mexicans Blame The U.S.

In Mexico, the drug war is viewed as a problem caused by the United States.

Carlos Rico, the head of North American affairs at the Mexican Foreign Ministry, says Mexico cannot resolve the problem of drug trafficking when such a huge demand exists for these drugs in the United States. The best we can do, he says of Mexico, is to try to make the passage through Mexico difficult for these criminal groups.

In addition, the weapons with which the cartels are killing cops, prosecutors and each other come primarily from the U.S.

As two of the nation's most powerful gangs, the Juarez and the Sinaloa cartels, battled in Juarez, the local police lost control of the border city. Over the course of last year, every type of crime from petty theft to robbery to extortion to murder mushroomed.

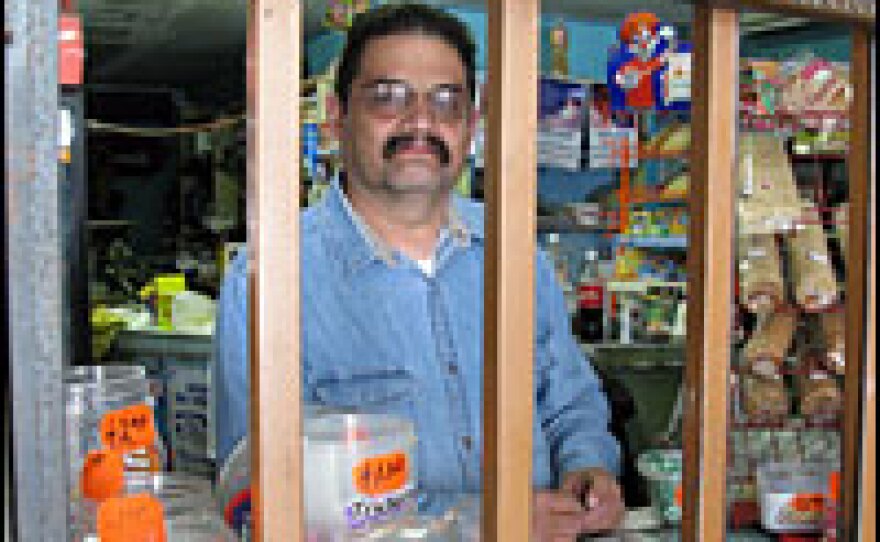

"We were closing the door, and these individuals arrived with guns drawn," says Miguel Navar, who runs a small convenience store in downtown Juarez. "They hit me and my wife and took all our money."

This shop has been in Navar's family all his life. He said that in the past they had never been robbed. Then last year they were robbed four times at gunpoint in six months. He says he's lost so much money that he's now on the verge of bankruptcy.

Last month, when the drug cartels ordered the Juarez police chief to quit, the federal government sent in the army to take over control of Juarez.

Eventually more than 8,000 soldiers and federal police will patrol the city's streets. But Navar says some of the soldiers are as bad as the criminals.

"There are some who are extorting money from merchants," Navar says. "In a place where they're supposed to be giving protection, they're bringing more fear."

Recently Navar installed thick metal bars across his front counter. He jokes that now he's living in a cage while all the delinquents are running around free.

Assessing Calderon's Efforts

But the arrival of the first wave of soldiers has reduced the number of drug-related killings in Juarez. In February, the city was averaging roughly 10 assassinations a day.

"Most Juarenses today are simply happy," says Tony Payan, an associate professor of political science at the University of Texas at El Paso. He also teaches at the university in Juarez. He says most people in Juarez are desperate for the government to find a way to control the bad guys.

"They're saying, 'Take them away. Give us our city back. The situation had gotten out of control, and we don't care what happens to these guys,' " he says. " 'If they die, if you disappear them, if you throw them out in the desert, we don't care, so long as you recover law and order.' "

Calderon has found himself on the political defensive. With more than 6,000 people killed last year in drug-related violence and no end to the war in sight, the president has been in the odd position of having to publicly justify why he's battling organized crime.

Calderon says the surge of violence is a sign that his forces are seriously disrupting the workings of the cartels. And the list of accomplishments in his drug war is quite long. Last year alone, Mexico seized thousands of tons of marijuana, 200,000 kilos of cocaine and hundreds of weapons. Several key leaders from several cartels were arrested. They've seized trucks, cars and jets used by the drug runners.

In July, the Mexican marines even snagged a submarine puttering off the Pacific Coast carrying more than five tons of cocaine.

What Calderon's administration has been unable to do is bring an end to the drug violence across Mexico.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))