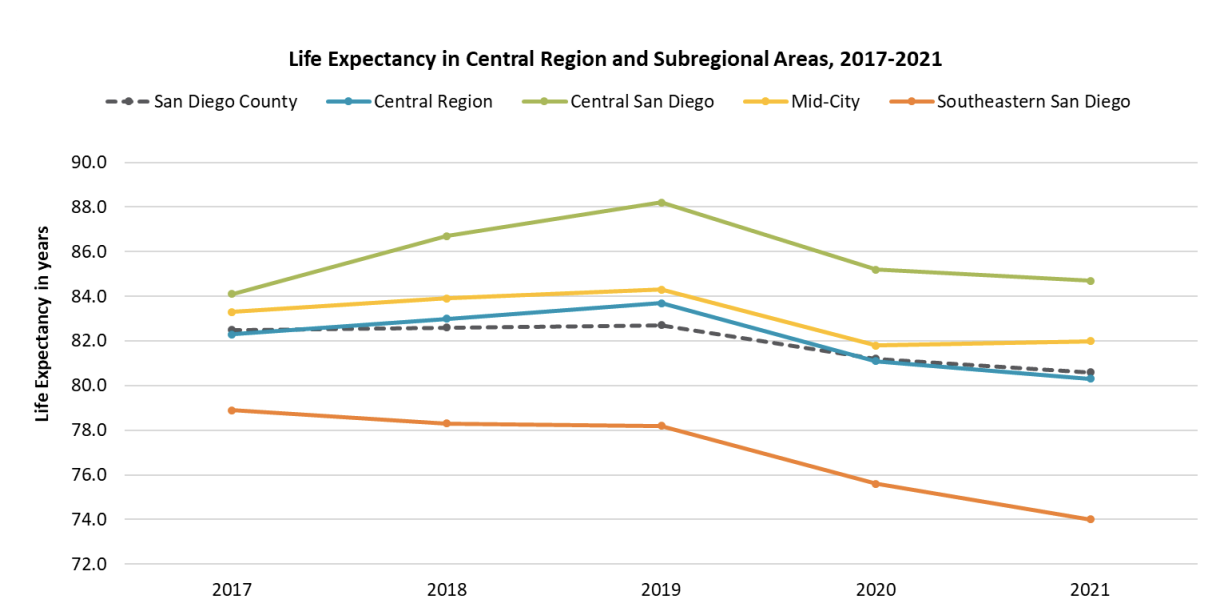

Barry Pollard has been tracking the data for years, watching the orange line that marks the life expectancy in Southeast San Diego steadily fall.

In 2017, residents lived to 79, on average. Now that number is 74. In neighboring Central San Diego, it’s almost 85.

Pollard co-chairs the Live Well San Diego Community Leadership Team that oversees the region that includes both areas. He worries the numbers and graphs will be lost on people, that the lines won’t communicate what it’s like to watch the people around you — your friends and family and neighbors — die younger than they should. Or that people will understand but feel resigned to it, including the residents.

“It's called community and toxic trauma,” he said. “It happens so regularly that people don't even think it is an issue. And so when you just look at the data, people yawn about it because their response — not only in health, but in a lot of ways, trauma affects people — and they'll go, ‘Oh, that's just the way the hood is. That’s just the way Southeastern is.’”

It’s like yelling fire in a burning building, but no one’s listening.

“It should be a state-of-damn-emergency over here,” Pollard said.

Nearly every indicator of health risk, including heart disease, asthma and cancer, is higher in Southeast San Diego than the other neighboring areas.

“I have to ask myself, if these numbers were in La Jolla, would everyone be so casual with them?” Pollard said.

He said the numbers show the symptoms of a complicated web of problems, but his team identified one thread to pull on first: the community has no 24-hour urgent care centers.

“They have a kid that suffers asthma at night and they got a bus,” he said. “They don’t have a car. It’s going to take them two to three hours to get to any one location.”

His team approached existing urgent care providers about changing that. Pollard anticipates at least one location offering extended evening hours in southeast San Diego sometime next year.

He said they will need to make community members aware of the option. Many currently rely on the emergency room.

“We have to let people know that they don’t have to leave their community to go get health care,” he said.

More is needed to close the gap, Pollard said: better health care and transportation, more Black and Latino physicians and wraparound services, complete streets with lights. The orange line on the graph won’t jump up overnight. But he hopes to turn around its trajectory.

“We didn’t get here overnight and we’re not going to be able to fix things overnight,” Pollard said. “But we can correct the ship, right?”

A spokesperson for the County Health and Human Services Administration could not provide KPBS with a breakdown of their spending by subregion, and did not say how leadership plans to respond to the data.

-

San Diego has seen more gray skies than normal this year, and the effects from May Gray and June Gloom can have an impact on mental health.

-