Since the age of 7, Herbert Siguenza has been obsessed with artist Pablo Picasso. Now, because the pandemic has forced The San Diego Rep to present its plays online, Siguenza has had the opportunity to turn his play "A Weekend With Pablo Picasso" into a film.

If there is an ever-so small silver lining to the COVID-19 pandemic forcing theaters to close, then it's that some productions that would have been lost after being performed live will now live on forever.

"I am so thrilled," Siguenza said about having "A Weekend with Pablo Picasso" being filmed. "It was just fate. There probably would be no film if there was no COVID. Right? I mean, COVID made all theaters become like movie studios. So when I approached Sam [Woodhouse, SD Rep artistic director] and Todd [Salovey, the stage director] saying, why don't we do it because we wanted to offer something to people and I said, well I'm ready to do Picasso. Why don't we do a movie? And they go, 'Yeah, let's do it, let's do it as a movie. Let's elevate the stage production.' And so I'm thrilled. I'm thrilled that this is this goes beyond the stage production. I think people are going to see an elevated version of the stage play."

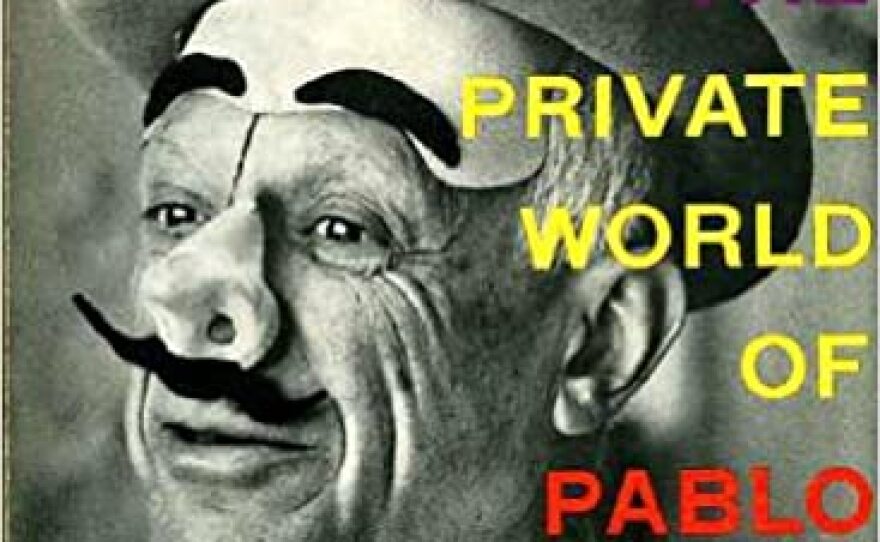

When Siguenza was 7 he was at a dentist's office where he saw a photo book called "The Private Life of Pablo Picasso" by David Douglas Duncan. Duncan spent a year with Picasso in his villa in the south of France and photographed him every day, painting, eating and playing with his kids.

"I was so impressed by this old man that at 76 painted wildly like a child," Siguenza recalled. "He played around with his kids. He had goats. He had a beautiful wife. He ran around in his underwear with no shirt. He just looked like a free soul, a very happy soul. And I told my mom, 'When I grew up, mom, I want to be like him. I want to be like this little old man.' And she says, 'Oh, no, he's Picasso. He's crazy.' But I never forgot that."

About 10 years ago he created the play "A Weekend with Pablo Picasso" and felt he was old enough to play the artist he saw in those photos decades ago.

What Siguenza grew to appreciate about that "happy soul" that captivated his 7-year-old mind was his activism.

"If you know my work, I'm a political artist," Siguenza said. "My work has always been about social justice. It's always been socially based. And Picasso, even though he was a pacifist, he was also a communist. He was also an activist. He also was a supporter of the peace movement. He reacted to things like the bombing of Guernica in 1937 in Spain. He produced one of the most horrifying political statements ever, which is the painting Guernica, right? It's just amazing and it's timeless, right? You could say Guernica represents the California fires. It represents all the horrors of humanity in this one painting. So he knew how to be a political artist. I don't think you want to be, but he did have to react to it. And that's my philosophy of art. It's not that I want to be a political artist. I just cannot sit around and not talk about what's going on in the country as it's burning. I have to react. I have to talk about it. If this was a peaceful society and everything was equitable and everything was beautiful, yeah, I would probably write for art's sake, but I don't think we're there yet. We're far from there."

Salovey, who has been with Siguenza on this journey with Picasso for a decade, said the play is about "creativity and about how to respond to life, daily life, the drama of life and the events of our world in an artistic and creative way... It's interesting in the play to see Picasso very disturbed about the brutality of the world around him. And also feeling that Picasso was a lifelong communist and then discovering that he no longer had an affinity with the Communist Party based on their actions. And what was amazing to me is he had to reinvent himself politically based on what he was seeing and he had to charge himself to say, is writing a letter enough, is talking to other intellectuals enough? But you have to do something that actually makes a statement. It's very inspiring for us. And you feel a big responsibility as an artist."

Siguenza's play asks us to go back to 1957 and spend three days with Picasso inside his private studio on the southern coast of France as he engages with art students. We as the audience are like the students sitting and listening to the master. Turning the play into a film allowed for a greater sense of intimacy with the audience.

"So there's an intimacy to it in terms of number and intimacy in terms of some of the issues that are being addressed and an intimacy just because it was a small crowd that you didn't have to push it out to," Salovey said. "And that was a really important step in the development of this piece toward becoming a film. Because when I was working with Herbert, I just began to notice that he didn't need to do as many gestures as he did on stage because the camera was close to him. And I watched his thinking as opposed to his gesturing. So in other words, he may have been talking about something and on stage, he would point to something on stage to give it a spatial expression. But it didn't need to be a spatial expression here. It could just be a facial expression. And it was really fascinating to say to Herbert through the making of the film, no, you don't have to do that. You can just be simpler with that. Just trust that."

To translate the play into a film, Salovey co-directed with Tim Powell. The film and the play both allow Siguenza to show off his own artistic abilities as he paints in Picasso's style during his performance.

"A lot of people don't know that I'm a trained artist," Siguenza said. "I did art for many years before I became an actor. And then I formed Culture Clash and, 35 years of doing theater. But Picasso is a bigger-than-life character, right? He is a bull in a China shop. And that's the way I play him. I'm basically playing my father. My dad was Spanish, his father was Spanish. So I'm from Spanish descent. So I can really relate to that old school machismo, men of that time, of the last century ... I celebrate that because that reminds me of my dad. I'm not that way. At least I don't think I'm that way. I'm a little more modern, but we have to come to terms with the fact that that's how men were at that time. It's not politically correct right now to be that way like Picasso. But you know what? He was just a man of his time, like Hemingway, like Miller, like all those guys, Diego Rivera, all those guys were the same, and so I'm playing a character and it's fun. It's fun because I get to be macho, I have the green light to be macho."

In doing the play over the years, some things can play a little differently.

Salovey explained: "When Picasso asks us what we want to create and are we doing things that we love with our life, are we doing things that we think are meaningful with our lives? To me, it lands like it never has before because the questions are fresher and more relevant than ever before. And the medium is one where we feel he is speaking to us more personally than ever before. Picasso says several times, I have to do something, I don't know what to do, but I have to do something. He's an artist. He feels he needs to create. He needs to contribute. He can't just be silent in the face of the oppressed and things that he doesn't feel are right. And I think that people watching it will strongly relate to what do I do now? What's my platform? What's my skill set? What are my talents? What's my voice? Ultimately, Picasso is about an artist who lives his voice in pottery and painting, in poetry every single day. But I think the film is a provocation of two things, one is what's your voice? What can you create and contribute creatively and artistically? And you should do that. And the second is and in a difficult, tumultuous time, how do you contribute to the conversation, bring things forward to a better way?"

The film version of "A Weekend with Pablo Picasso" starts streaming this Thursday and will be available until Oct. 14. You can purchase a ticket for $35 online now.