Cecil Garland thought he was getting as far away as possible when he bought a fledgling ranch in Callao, Utah, more than 30 years ago.

Callao, with its five ranches and 35 people, is 50 dusty miles from a paved road, 90 miles from a gas station or grocery store, and about 300 miles from Las Vegas.

But Garland is convinced that distant and urban Las Vegas threatens the springs and wells that make ranching possible in Callao, and in thousands of square miles of high desert valleys between Callao and Las Vegas.

Water officials in the Las Vegas Valley have launched major conservation efforts and they're seeking water elsewhere, but they've lusted after groundwater beneath rural valleys to the north for more than 15 years. It may be the easiest to access, given significant political and technological problems with other plans. So, they've applied for water rights in seven sparsely populated valleys, a region bigger than Connecticut, including the Snake Valley, which stretches into Utah and to Callao.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority and its water "czar," Patricia Mulroy, hope to eventually tap 65 billion gallons of rural water a year with a 300-mile-long pipeline expected to cost more than $2 billion. That's enough water for 50,000 families a year.

"There isn't enough water to go around," Mulroy told NPR in a 1991 story about the early stages of the project. "And we're the most arid spot in the United States."

Back in 1991, the Las Vegas Valley was the fastest-growing region in the country. People were moving in at the rate of 5,000 a month then, overwhelming schools, roads and other infrastructure, including the water system. As Mulroy noted, the valley gets little rain. Leave a bucket outside all year long in an average year and it'll collect just four inches of water.

Las Vegas taps groundwater from the valley beneath it and surface water from the Colorado River nearby. But neither is enough for the region's phenomenal growth. The valley has nearly doubled in population since 1991, to 1.5 million. Las Vegas gambling resorts now attract close to 40 million visitors a year.

So, for close to two decades, Mulroy has been working persistently to acquire "rights" to water in rural counties north of the Las Vegas Valley. She noted back in 1991 that there is an economic imperative to taking water from rural counties largely dependent on ranching, and bringing it to the big city.

"Ninety percent of Nevada's water goes to agriculture and generates 6,000 jobs, which is less than the Mirage Hotel generates," Mulroy said at the time. "The West was settled by the federal government as an agrarian economy (but) it isn't that anymore …The West is becoming an urban area."

Rancher Cecil Garland is not convinced.

"What Las Vegas has got to learn is that there are limits to its growth," Garland says. He also applies his own value judgment to the competing uses for water.

"Gluttony, glitter, girls and gambling are what [Las Vegas] is all about," the 81-year-old rancher asserts. "What it's all about here [in Callao] is children, cattle, country and church." Then Garland raises a fundamental question. "Would it be crops or craps that we use our water for?"

Casino mogul Steve Wynn told NPR in 1991 that it is shortsighted to dismiss Las Vegas as an expendable place.

"This isn't like a farmer who grows wheat. That's necessary," Wynn began. "Going on vacation is not necessary. But to the people who live [here] and who have families and children [here], and to this state, this is necessary, because otherwise we all have to go someplace else."

Water czar Patricia Mulroy has always insisted that it's possible to use rural water for both rural and urban needs. Her Southern Nevada Water Authority is not seeking access to water that is already used by ranchers and farmers, except in the case of five ranches it has purchased outright for their water rights. But there's deep concern in the rural valleys that any drilling and pumping of water for Las Vegas will stem or stop the flow to existing wells and springs used by wildlife, livestock and crops.

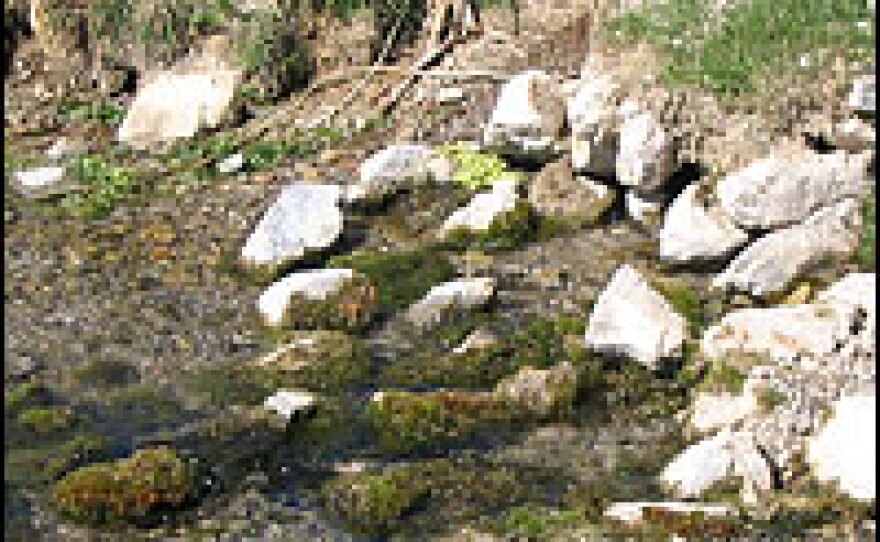

"It'll become a dry desert valley," says Dean Baker, a rancher at the southern end of Snake Valley, 70 miles south of Callao and about 200 miles north of Las Vegas. "The reason there's ranching in this valley is because there's water from these springs."

Baker takes visitors to a spring-fed pond and watering trough to illustrate his fear. Wild horses, geese, ducks and sheep found water there until a rancher expanded his operation and dug a new well. The pond is now bone dry and lined with crispy and skeletal cat-tails and rushes. The trough is empty.

"It's happened around everyplace we're pumping," Baker confesses. "Probably if southern Nevada hadn't come along with this huge plan to do many times as much [drilling and pumping] we'd have tried never to let anybody know what we'd done. But it's the best example of why we know [the Las Vegas plan] won't work."

Baker and others say they believe that the aquifers beneath the northern valleys are connected and that drilling and pumping in one place would diminish the flow of water elsewhere. Indeed, a newly released draft report from the U.S. Geological Survey concludes that the underground water system is interconnected. The report also indicates there's plenty of water for Las Vegas and the rural valleys.

The Nevada State Engineer is responsible for determining whether the Las Vegas valley will get the water it seeks beneath Nevada valleys. Utah water officials must also approve any plan that could affect water beneath Snake Valley, since it lies in both states.

So far, Nevada State Engineer Tracy Taylor has ruled on the southern Nevada water applications for just one of the rural regions, Spring Valley, which is adjacent to Snake Valley. Taylor's legally complex, 56-page ruling is summarized this way by his boss, Allen Biaggi, director of Nevada's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources:

"This [water] is all underground. It's unseen. [So] there's a lot of uncertainty," Biaggi explains. "We really don't know what's going to happen here until we do some pumping and see how this natural system reacts to that pumping."

Nevada State Engineer Taylor has awarded southern Nevada about one-fifth of the water it sought, but only conditionally. The underground water system must be studied first, and then pumped and monitored closely for 10 years. If other wells and springs begin to lose water, pumping for Las Vegas could be curtailed.

But ranchers in the northern valleys worry that there's no stopping the flow of water south once a multibillion-dollar pipeline is built and filled.

Some in the region say their future and their children's future are at stake.

"It's very simple," says Denys Koyle, owner of the Border Inn, a gas station/casino/restaurant/motel right on the Utah-Nevada border in Snake Valley. "Without water, even [with] decreased water, the future's going to go away."

Mulroy of the Southern Nevada Water Authority insists that there's more to this water fight than water.

"There is that north-south acrimony in Nevada," she said recently. "There's a cultural gap. There's a rural-urban gap. And overcoming those is probably the most daunting part of this job."

On Wednesday, in Part 2 of Morning Edition's water series, Ted Robbins provides the view from Las Vegas, and a profile of Mulroy, as she desperately seeks water for one of the driest and fastest-growing regions of the country.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))