About 138,000 U.S. military members have been added to the Veterans Affairs Department's disability compensation rolls since 2001. Each year, a few hundred of them seek grant money from the VA to make their homes handicapped-accessible.

But some veterans are finding they aren't eligible because their injuries aren't covered under the law, and they want Congress to do something about it.

Navigating a Home Blind

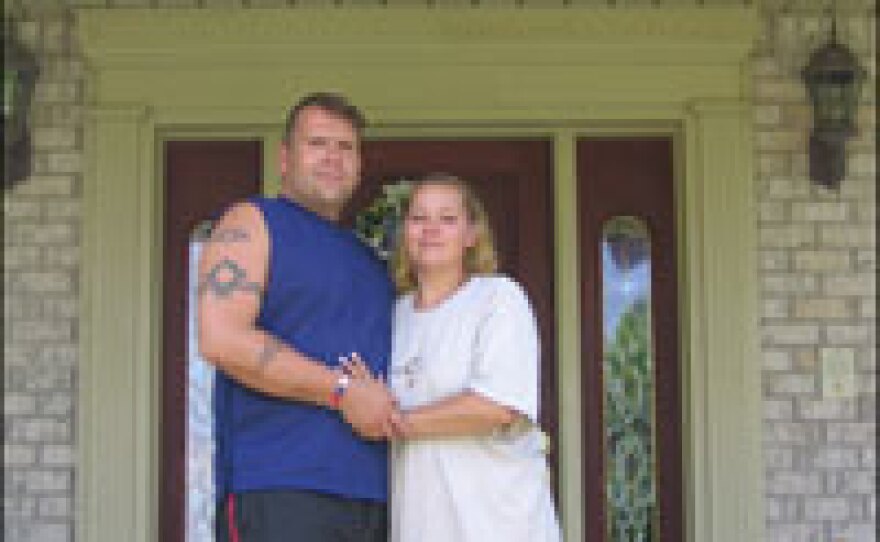

One serviceman whose injuries aren't fully covered is retired Army Staff Sgt. Jason Pepper, whose bright blue eyes are prosthetics — a casualty of a 2004 attack in Karbala, Iraq. The incident earned him a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star but also left him blind, with shrapnel in his brain, a shattered right arm and a surgically reconstructed left hand. After two years of rehabilitation, he settled his family in a rural area south of Nashville, Tenn.

Pepper trails his hand along the walls to find his way around the house. That works fine everywhere except the kitchen, says his wife, Heather.

"He'll skirt the oven, and even this part gets hot. And we'll right away jump, 'Jason, you're going to burn yourself!' And so I'm looking forward to getting a new stovetop really bad," she says.

Replacing the electric coil stovetop is just one of the pricey renovations the Peppers need in order to make the home safe for Jason. The Peppers say they're going thousands of dollars into debt for no-slip tiles for the bathrooms, talking appliances and a railing for their porch.

That isn't what they'd planned. Jason Pepper applied for a program called the Specially Adapted Housing grant, which offers vets up to $50,000 to make their homes handicapped-accessible. But the VA representative handling his case told him he qualified for just $10,000 for his blindness.

Pepper recalls their conversation: "She's like, 'What's the amputation?' And I'm like, 'Well, it's my index finger.' And she's like, 'Well, that doesn't help at all. If you were to lose your arm from the elbow up, or if you were to lose a leg, then you'd qualify for the $50,000.' So, you know, I fired back with 'Well, haven't I lost enough?'"

Guidelines Put Focus on Amputees

Keith Pedigo, who heads the VA's Loan Guarantee Service, says Pepper's feelings are understandable.

"Well, I can certainly understand why they would feel that way. If you've been injured as a result of military action, then certainly you've given a lot, and it's totally understandable that many would have that view," Pedigo says.

However, Pedigo says, the program operates under guidelines provided by Congress — and the statute is "pretty clear-cut."

For veterans to get the full $50,000 Specially Adapted Housing grant, they would have to lose an arm or leg from the knee or elbow up. A few inches lower and they might be out of luck.

Brian Lawrence of the advocacy group Disabled American Veterans says the law's focus on amputees stems from the types of injuries prevalent in past wars.

"Those types of injuries were more typical to the type of warfare that we associated with landmines, [which] were largely used in Vietnam and Korea and World War II," he says.

Lawrence says that now, body armor and improved medical technology have soldiers surviving injuries that previously would have killed them. He says the current eligibility requirements for the adapted-housing program are fair.

"The higher the amputation, the less mobile they are — and the more they'll have to rely on alterations in housing to function normally," Lawrence says.

Changes in Disability Requirements Not Likely

U.S. Rep. John Boozman of Arkansas, a ranking member of a subcommittee reviewing the grant program, agrees.

"The fairest, you know, the most efficient way seems to be some sort of a ranking order. That's how it's been done in Social Security disability, that's how it's been done in private disability, workman's comp, things like that," Boozman says. "So I think the VA has just followed the model that's been pretty much the standard throughout the industry."

Boozman says Congress is constantly reviewing the law. Last year, it was amended to allow veterans to use it more than once. This year, there are proposals to add burn injuries to the eligibility list and to raise the grants to keep pace with inflation. There are no plans to change the disability requirements.

The Peppers, meanwhile, did not appeal. They have refinanced their home, and a local church group is donating a new stovetop.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))