The booming city of Fontana, Calif., is a thick sprawl of closely packed subdivisions. People who couldn't afford a home in Los Angeles or San Diego could buy one here — in San Bernardino County, about 50 miles east of Los Angeles.

But as housing values tumbled — and subprime mortgages ballooned — Fontana became one of the many epicenters of foreclosures in Southern California.

In San Bernardino County last year, more than 7,700 homeowners lost their homes to foreclosure — a 719 percent increase in just one year.

Janice Rutherford is a city councilwoman in Fontana. Her neighbors lost their house to foreclosure. She figures they paid about $250,000 for the house.

By the time the bank repossessed it, the neighbors owed more than twice that amount: They had borrowed repeatedly against its inflated value, and when values slumped, they were "upside down" on their mortgage — with negative equity.

Stories similar to this — of people using their property like ATM machines — are plentiful in this region of Southern California, known as the Inland Empire.

"I feel bad that people got themselves in over their heads. People in these houses borrowed against the future, spent money they didn't have. Our government does the same thing, so it's no surprise that people think, 'Hey, this is the way to do it,' " Rutherford says.

And when housing tanks — and the economic forecast for the future looks gloomy — everyone feels the pain, from car dealerships to housing contractors.

Marty Stout, chief operations officer for Mayer Roofing, says that at the peak of his company's business in 2005, it had 850 roofers working for it. Now, there are 200.

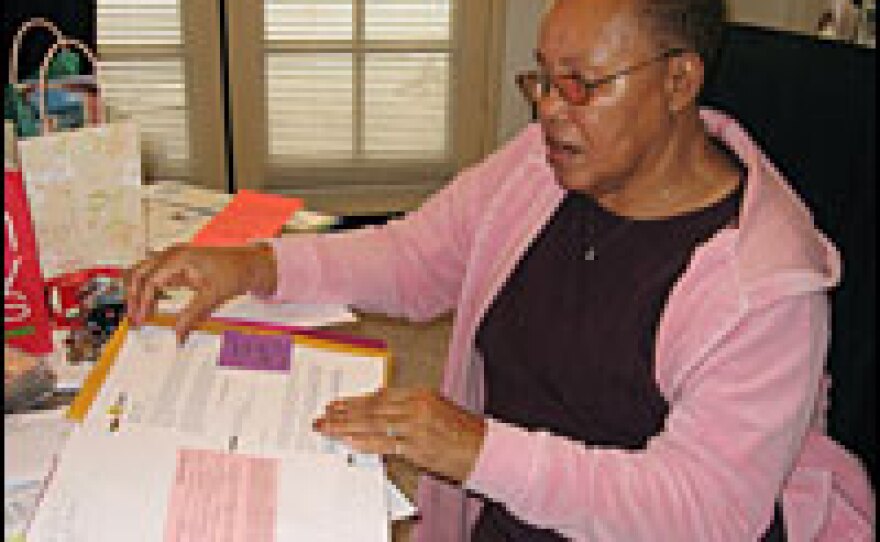

Betty Larkins, of Moreno Valley, Calif., is another homeowner who is feeling the pain of foreclosure. She fell victim to what she calls a "ridiculous re-fi," and her monthly mortgage payment soared to $3,000 from $1,700. With just her Social Security and pension income, she couldn't keep up.

Larkins fended off foreclosure for a while. But now, her house has sold at auction. She has to be out by next Wednesday.

Larkins says she recognizes her own story when she reads about foreclosures in the paper.

"I say, 'Gosh, here's another one of me. Gosh, what's happening with the world?' All of it is not necessary, that's my thought," she says.

And in 2008, people expect the foreclosure rate to spike again — with another batch of adjustable mortgages due to reset at higher rates.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))