First in a two-part series.

It was called The Rock — the country's only escape-proof prison. The federal penitentiary at Alcatraz was a cell house built on an island surrounded by the frigid waters of the San Francisco Bay.

Only the worst of the worst were sent there, lifers like Frank Morris and John and Clarence Anglin. But from the moment the three men arrived, it was clear they did not intend to stay.

On June 12, 1962, they vanished, launching the largest manhunt of its time, one that has continued to this day.

Active Pursuit

The U.S. Marshals Service is still actively pursuing the case on the chance that the three men pulled off one of the most daring prison escapes in U.S. history.

"Leads still come in. I just got one a couple weeks ago," U.S. Marshal Michael Dyke said recently in his office in Oakland, Calif., as he poured over a stack of old file folders from the case.

"Here's one that says they were in a small town in Alabama living on the farm," Dyke says, flipping though pages. "Here's one saying they came to her house when she was a little girl, and she says her father told her as a child that Clarence Anglin used to come to her house regularly."

Dyke has been in charge of the 1962 Alcatraz escape for seven years now. It has always captured the public's — and Hollywood's — imagination: three bank robbers, a notorious prison, an ingenious plan. Back then, it filled the airwaves for months as newsreel footage showed the Coast Guard and police scouring the bay.

Even now, Dyke says it's hard not to root just a little for the bad guys, to wonder if maybe the three men found a way to freedom.

But it doesn't matter, Dyke says. He has a job to do.

"There's an active warrant and the Marshals Service doesn't give up looking for people," he said. "In this case, this would be like saying, 'Well, yeah, they probably are dead. We're going to quit looking.' Well, there's no proof they're dead, so we're not going to quit looking."

Proof of death. It's the one thing that has flummoxed local police, the Coast Guard, the Bureau of Prisons, the FBI and the Marshals about this case for almost 50 years. Statistically, the majority of bodies that drown in the bay float to the top after a few days. In this case, not even one of the bodies surfaced. They all simply vanished.

Escaping Alcatraz

It all started when Morris and the Anglins devised an intricate plan more than six months earlier. They stole prison-issue raincoats to craft a boat and life vests. They molded soap and paper into life-sized heads with hair, lips and eyebrows, real-enough looking to place on their pillows and fool guards into thinking they were sleeping. They stole tools and kitchen spoons to chip away a hole in the back of their cells big enough to crawl through.

As U.S Park Ranger John Cantwell makes his way down the large corridor of the main cell house on Alcatraz, he stops in front of Morris' and the Anglins' cells.

"You can see the holes," he says, pointing to the back of the men's cells. "That's a fairly large hole to climb through. Those are the original holes that these convicts constructed."

Inside one of the cells, Cantwell picks up a cardboard vent cover the men made to cover the holes. It still looks real.

"You hang a couple of coats, maybe a towel in front of it and it camouflages that portal into the utility corridor," he says.

The utility corridor is a small passage right behind the cells. Cantwell squeezes in through a side door.

"If you look up you can see the plumbing they actually used as a ladder," he says.

At the top of the plumbing is a landing. Morris and the Anglins convinced officers to allow them to clean and paint this landing during the day, hidden behind a cloth. What they were really doing, however, was gluing their raincoat raft together using a technique they learned from Popular Mechanics magazine.

Cantwell points to the ceiling, which Morris and the Anglins were supposed to paint.

"You can see the actual paint [line] where they stopped," he says. "So they did start their maintenance job, they did paint half the ceiling."

Soon the raft and life vests were ready. And on the night of June 11, 1962, the men climbed up the plumbing to the landing and pushed themselves through an air vent in the ceiling to the roof above.

Cantwell makes his way up an old rickety staircase and finds the air vent on the roof.

"All they had to do is just kick it off," giving the vent a tap with his foot. "They're on the roof now and they run across the rooftop trying not to make too much noise."

Cantwell runs to the edge of the roof and stops at a water pipe.

"They slid down the pipe, hopped over that fence, then went down that staircase, past the morgue," he says. "They ran past those water tanks, then down that hillside to the east side of the island. Where the smokestack is is basically where they entered the water."

'Totally Normal Night'

Bill Long was the lieutenant in charge of the cell block on the midnight to morning shift that night. He never heard a peep.

"Totally normal night for me," says Long, 85, who now lives in rural Pennsylvania. "I worked all night up through this."

His shift that night was quiet. But he remembers a few odd things that happened on the shift before his. A lieutenant reported a loud bang he described as a hubcap rolling on the floor — or was it an air vent being popped onto a roof? And another officer reported hearing what he thought were footsteps above him.

But it came to nothing, until Long ordered the morning count.

"The men went around the gallery to count and when they did the man on B1 didn't come back," Long said.

Long went to find him.

"He was hotfootin' it down toward me and he says, 'Bill, Bill, I got a guy who won't get up for count!'" Long remembers. "Well I said, 'Sarge, I'll get him up.' So I went down to the cell, get down on my knee, put my head against the bar. I reached my left hand through the bars and hit the pillow and hollered, 'Get up for count!'"

Then he says he almost had a heart attack.

"Bam, the head flopped off on the floor," Long said. "Oh, I thought right then that there was a head that fell off on the floor. They said I jumped back four feet from the bars. I mean, the most unexpected thing you could almost imagine."

Long ran to the phone and sounded the alarm.

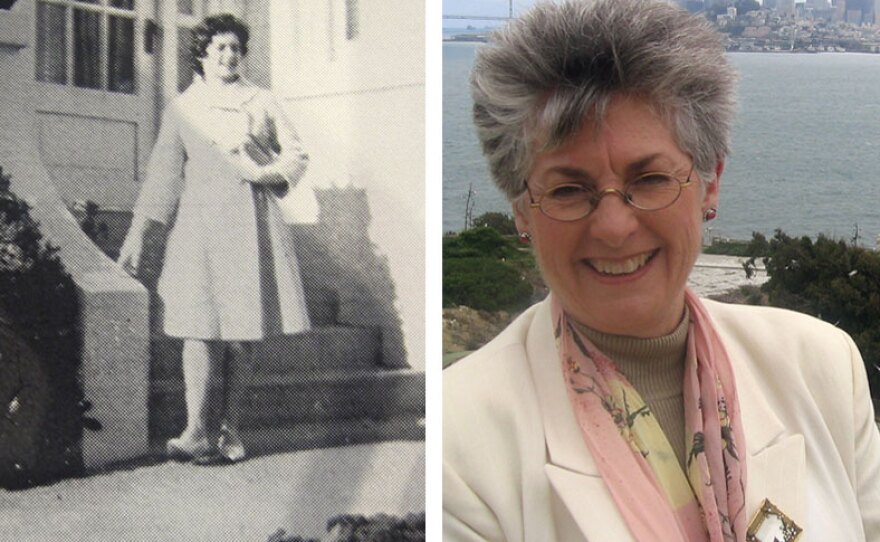

Fifteen-year-old Jolene Babyak, daughter of the acting warden, was lying in bed in the officer's quarters.

"The siren woke me up," she says. "They called my father and he opened the safe."

The safe held plans for action in case of an escape attempt.

"So he put that whole thing into motion," Babyak remembers. "They called Washington, D.C. They alerted the newspapers. They used to say it was the biggest manhunt since the Lindbergh baby kidnapping."

Boats scoured the bay and far out into the ocean. Officers searched every corner of the island. Local police for hundreds of miles looked for any sign of the men.

But Frank Morris, John Anglin and Clarence Anglin were never seen again.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))