NPR has been profiling some of the Republicans who are considering a presidential run in 2012, to find out what first sparked their interest in politics. Read more of those profiles.

You may not be ready yet, but in Iowa, they're already thinking about 2012.

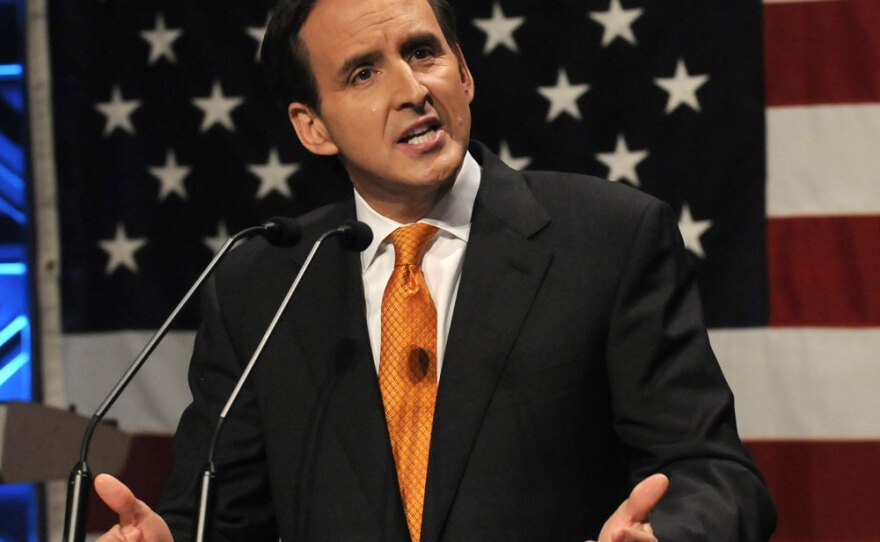

In the tiny town of Fayette, the local Republican Party is holding a fundraising lunch. It's a small event — but not too small for Tim Pawlenty.

Tall and trim, with a good head of hair, Pawlenty shakes every hand in front of him. He just wrapped up two terms as governor of Minnesota, and now he's selling himself to Iowans as the guy who brought small government to those liberals up north.

"The land of ... Hubert Humphrey and Paul Wellstone, and now United States Sen. Al Franken," Pawlenty tells the crowd. "As Frank Sinatra would sing about New York, if we can do it there, we can do it anywhere."

Working-Class Roots

Of course, these days it's also the land of the Tea Party's favorite congresswoman, Michele Bachmann. It's actually been awhile since Minnesota was reliably liberal, and Pawlenty's career parallels that shift from blue to purple. It's a career, he says, that got its spark not from any single political issue or event — but from a person.

"It really was Ronald Reagan," Pawlenty says. "It really looked like America was in a mess, and here we had this strong, optimistic candidate emerge in the form of Ronald Reagan. And that was really the first experience I had with politics — and he really inspired me."

Now, you might be thinking that's a safe answer. These days, even President Obama claims to be inspired by Reagan. But it wasn't such a safe answer 30 years ago in Pawlenty's blue-collar neighborhood in South St. Paul. As he recalls it, everybody there was a working-class Democrat — people who thought Republicans were out to get them.

Pawlenty's uncle Virgil recalls the debates between young Tim and his father, Gene.

Because he is so personally engaging and such a nice person, [Democrats] simply have to demonize his politics, because he can't be demonized personally.

"It was a lot about the union, business and sometimes a little politics," he says. "And they would have a back-and-forth, because Gene was a truck driver."

At times, he was an unemployed truck driver. There were a lot of out-of-work people in South St. Paul after the local stockyards shut down. Nationwide, many of these people eventually embraced Reagan — the "Reagan Democrats" of 1980, a political shift the teenage Tim Pawlenty got a jump on. And he wasn't shy about telling people what he thought, according to his aunt Judy.

"When he was in high school, I guess he questioned a lot of things. And like I say, he was very up on what was going on in the world," she says. "So the kids started calling him 'senator,' and it just kind of stuck."

Pawlenty's campaign says the nickname thing never happened. But you hear the story a lot — it says something about local memories of young Tim's eagerness to move on to bigger and better things.

A Religious Transformation

Holy Trinity, the parish where Pawlenty grew up, is still in a lot of ways that old Minnesota — a church with a strong religious and ethnic identity, in this case, Polish Catholic. The liturgy is traditional, and the blue-haired ladies still hold coffee hour in the basement — just as they do in so many other Lutheran and Methodist and Presbyterian church basements.

Midway through the Reagan administration, Pawlenty moved on to something a little more up to date: Wooddale Church, a Protestant megachurch with two campuses southwest of Minneapolis. Wooddale has everything Holy Trinity lacks — a real coffee shop, an 1,800-seat "worship center" and a sound system operated by a guy who used to work for Prince.

This is post-Reagan Minnesota: suburban, nondenominational, post-ethnic and trending Republican.

"It was just the next step in his life and in his journey," says Leith Anderson, the senior pastor at Wooddale and president of the National Association of Evangelicals. Anderson still remembers talking to his wife after one of his early encounters with Pawlenty.

"I said, 'You know, I think he's really going to be a significant government leader.' And she said, 'Like what?' And I said, 'I don't know, like president of the United States,' " he says. "I don't claim to be a prophet, but I was impressed."

Minnesota's 'Fiscal Mess'

Pawlenty has made an issue of his faith lately. His autobiography brims with Bible quotations, and the Almighty gets a shout-out in his Iowa stump speech: "We need to be a nation that turns toward God, not away from God."

To underscore the point, Pawlenty also tweeted that sentiment, nearly verbatim.

But at the Minnesota Capitol, where Pawlenty spent two decades jousting with Democrats — first in the House, then as governor — religion rarely came up.

"You didn't hear that a lot in his rhetoric as governor," says Democratic state Sen. John Marty. He says the real struggle was about money — specifically, the governor's Reaganesque hostility toward taxes, which Marty believes led directly to the state's current $5 billion budget deficit.

"He's the first governor to leave the state with a fiscal mess," Marty says.

Democrats say Pawlenty kept his no-new-taxes pledge by deferring needed investments in education and infrastructure, and that the bill is now coming due.

Pawlenty's defenders, meanwhile, say it's not fair to blame him for the current fiscal crisis.

"The Democratic side of this equation has got a good story," says attorney Dennis O'Brien, who in the 1980s gave Pawlenty his first law job. "But the low-tax, grow-the-economy, generate-revenue [viewpoint] is always a substantial, intellectually coherent perspective."

O'Brien acknowledges there's still a lot of lingering anger at Pawlenty — "rancor," he calls it. But he says it comes from the fact that Pawlenty has always been so politically frustrating for Minnesota liberals.

"Because he is so personally engaging and such a nice person," he says, "they simply have to demonize his politics, because he can't be demonized personally."

Another echo, perhaps, of Ronald Reagan — that personally engaging guy who so enraged Democrats three decades ago.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))