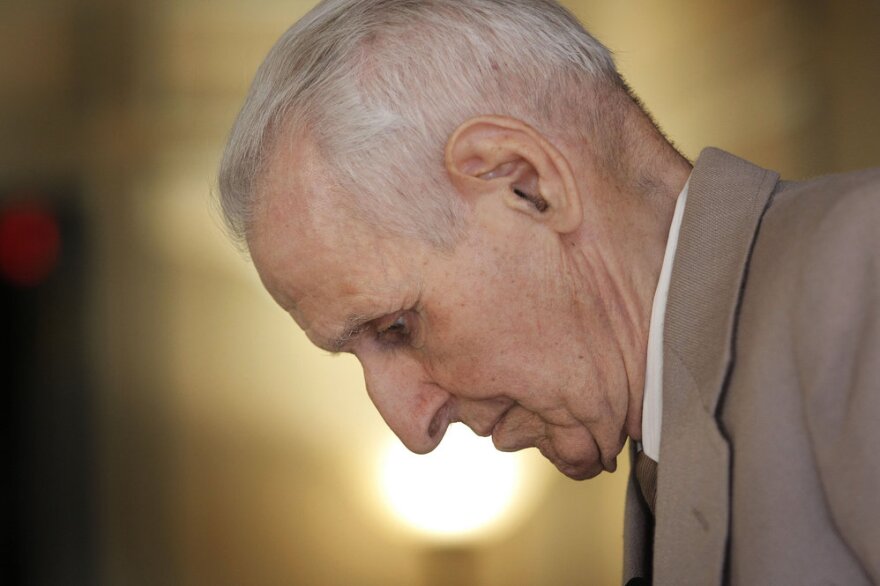

Dr. Jack Kevorkian, the assisted suicide advocate, died Friday at 83. Supporters say he was a compassionate caregiver who paid a steep price for helping chronically and terminally ill patients end their suffering. Critics, however, say Kevorkian's zealotry clouded his ability to behave like a responsible physician.

It will be very interesting 50 years from now to see whether Kevorkian is regarded by history as this sort of a bizarre crank or whether he'll be regarded as a modern medical pioneer.

Kevorkian claimed to have assisted in the suicides of at least 130 people with the help of machines he invented. He called one the "Thanatron," or death machine, and another the "Merictron," or mercy machine.

"It will be very interesting 50 years from now to see whether Kevorkian is regarded by history as this sort of a bizarre crank or whether he'll be regarded as a modern medical pioneer," said Jack Lessenberry, who wrote about Kevorkian for The New York Times and Vanity Fair. "I think we simply don't know."

(Lessenberry is also a paid political analyst for Michigan Radio.)

Kevorkian first captured the public's attention in 1990. That's when Janet Adkins climbed into the back of his VW van in a suburban Detroit park, laid down and waited as Kevorkian put a needle into her arm. Adkins pushed a button on a machine and released a painkiller and a poison that killed her quickly, sparing her from a future with Alzheimer's disease.

After a string of acquittals through the 1990s, a newly elected prosecutor said he didn't plan to bring charges against Kevorkian in any more cases. And the right-to-die cause was gaining traction nationally.

But in 1998, Kevorkian helped Tom Youk, who had Lou Gehrig's disease, commit suicide. Kevorkian then sent a video of the process to the news program 60 Minutes.

In the video, Kevorkian asks Youk if he wants to go ahead with the procedure. "Shake your head yes if you want to go," he says.

The difference this time was that instead of the patient pushing a button, Kevorkian administered the lethal injection.

"A couple of my top administrators were at my house, we were watching the TV, and we all looked at it and said, 'Oh, this is going to be a bigger headache than we thought," says David Gorcyca, Oakland County prosecutor at the time of the broadcast.

"He was begging to be prosecuted," Gorcyca said.

Kevorkian was charged. He decided to represent himself at trial, and a jury convicted him of murder.

Lessenberry said Kevorkian believed his conviction would be a catalyst for the right-to-die movement.

"What he thought was once he was convicted, people would surround the prison and demand his release and the world would be safe for euthanasia. But when he was convicted he looked at me — I was in the courtroom — and said, 'I've got them right where I want them.' And they hustled him away. And the prosecutor looked at me and said, 'Prisoners don't usually get to hold press conferences.'"

Kevorkian served eight years in prison. Once he was released in 2007, he kept a relatively low profile. He did some lectures and was scheduled to start a book tour later this month.

But he went into the hospital a few weeks ago with pneumonia and kidney problems. He died in the middle of the night after a blood clot from his leg traveled to his lungs.

Attorney Geoffrey Fieger, who represented Kevorkian for almost a decade, said the fact that his long-time client did not end his life in the same way he advocated takes nothing away from the cause in which he believed.

"So you might say in a way, is it rather ignominious that Dr. Kevorkian in the end didn't choose to end his life the way that he helped patients? And I don't really believe so. I think everyone chooses the very end for themselves."

Another attorney and friend who was with Kevorkian in the hospital said the nurses who cared for him played the music of Johann Sebastian Bach at his bedside in his final hours. Kevorkian once said in an interview that Bach was his god.

Copyright 2022 Michigan Radio. To see more, visit Michigan Radio. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))