Decrying a "partisan three-ring circus" in the nation's capital, President Obama criticized a newly minted Republican plan to avert an unprecedented government default Monday night and said congressional leaders must produce a compromise that can reach his desk before the Aug. 2 deadline.

"The American people may have voted for divided government, but they didn't vote for a dysfunctional government," the president said in a hastily arranged prime-time speech. He appealed to the public to contact lawmakers and demand "a balanced approach" to reducing federal deficits.

"The president is asking for something that is in neither one of the congressional plans that is now under consideration: tax increases," NPR National Political Correspondent Mara Liasson told NPR's Robert Siegel. "Harry Reid's plan, which he says he prefers, doesn't have revenue increases, it doesn't have entitlement reform or tax reform. So he's asking for something that's not on the table right now."

Obama stepped to the microphones a few hours after first Republicans, then Democrats drafted rival fallback legislation Monday to avert a potentially devastating government default in little more than a week. He said the approach unveiled earlier in the day by House Speaker John Boehner would raise the nation's debt limit only long enough to push off the threat of default for six months. "In other words, it doesn't solve the problem," he said.

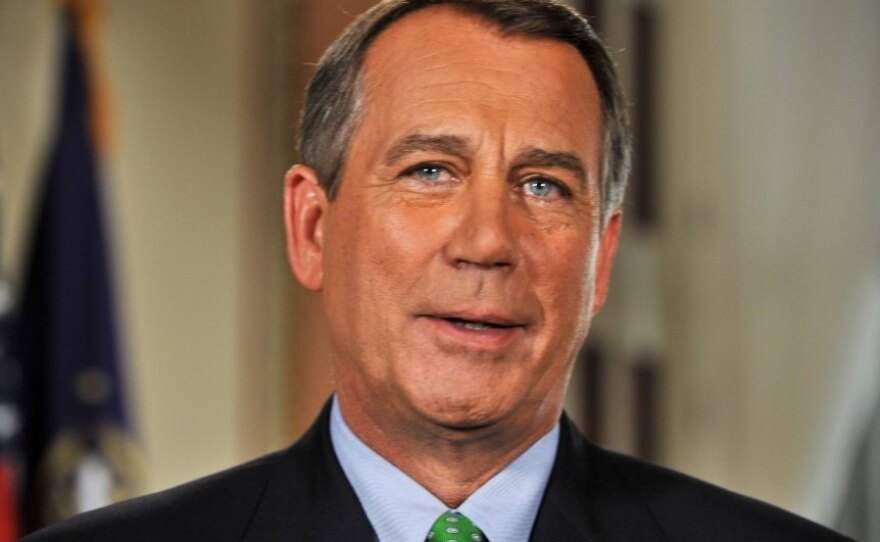

The president had scarcely completed his remarks when Boehner made a rebuttal carried live on the nation's networks.

"The president has often said we need a `balanced' approach, which in Washington means we spend more, you pay more," the Ohio Republican said, speaking from a room just off the House floor. "The sad truth is that the president wanted a blank check six months ago, and he wants a blank check today. That is just not going to happen."

Directly challenging the president, Boehner said there "is no stalemate in Congress."

He said the Republicans' newest legislation would clear the House, could clear the Senate and then would be sent to Obama for his signature.

It's unclear if the Republican measure can clear the Democratic-controlled Senate.

"His bill is one that is not going to get much traction in the Democratic-run Senate largely because it was a bill that was drawn up by House Republicans and probably with collaboration of Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell," NPR's David Welna said. "But I found it somewhat disingenuous for Boehner to say that this is the bill that's going to solve the problems because he didn't mention the fact that this is a piece of legislation that would require two different votes for raising the debt ceiling: one right now and another probably early next year sometime in the midst of next year's campaigns. That is the biggest objection of the White House to what Boehner is proposing."

The back-to-back televised speeches did little to suggest that a compromise was in the offing, and the next steps appeared to be votes in the House and Senate on the rival plans by mid-week.

"Usually when a president asks for time from the networks to make an evening address and speaker of the House answers him, you'd think they were announcing some kind of historic deal or a solution to the problem," NPR's Liasson said. "Instead they both got up to do what they've been doing more or less for the past several months, which is to explain why the other guy's idea is really bad and why the stalemate is somebody else's fault. And I think the American people and certainly the financial markets are probably running out of patience with this."

But despite warnings to the contrary, U.S. financial markets have appeared to take the political maneuvering in stride so far. Wall Street posted losses Monday but with no indication of panic among investors.

"I think there's still a feeling in the markets that eventually this will be worked out and most importantly the interest rates on Treasury debt remain low and stable. ... and it really hasn't budged much," said Uri Berliner, NPR's business editor.

Without signed legislation by day's end on Aug. 2, the Treasury will be unable to pay all its bills, possibly triggering an unprecedented default that officials warn could badly harm a national economy struggling to recover from the worst recession in decades.

Obama wants legislation that will raise the nation's debt limit by at least $2.4 trillion in one vote, enough to avoid a recurrence of the acrimonious current struggle until after the 2012 elections.

Republicans want a two-step process that would require a second vote in the midst of a campaign for control of the White House and both houses of Congress. Liasson noted that the White House is against this approach, and for a while the House Republican leadership was, too.

But "they [now] feel that every time they have this debate, every time they can talk about a balanced-budged amendment, every time they can put the president on the defensive and say, 'If only you agree to these spending cuts, we would raise the debt ceiling,' they feel that that's actually good for them," she said.

There were concessions from both sides embedded in the competing legislation, but they were largely obscured by the partisan rhetoric of the day.

Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky urged Obama to shift his position rather than "veto the country into default." And Reid jabbed at Tea Party-backed Republicans who make up a significant portion of the House GOP rank and file. The Nevada Democrat warned against allowing "these extremists" to dictate the country's course."

The measure Boehner and the GOP leadership drafted in the House called for spending cuts and an increase in the debt limit to tide the Treasury over until sometime next year. A second increase in borrowing authority would hinge on approval of additional spending cuts sometime during the election year.

Across the Capitol, Reid wrote legislation that drew the president's backing, praise from House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi and criticism from Republicans.

The Democrats' measure would cut $2.7 trillion in federal spending and raise the debt limit by $2.4 trillion in one step, enough borrowing authority to meet Obama's bottom-line demand. The cuts include $1.2 trillion from across a range of hundreds of government programs and $1 trillion in savings assumed to derive from the end of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Material from The Associates Press was used in this report

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))