The perennial presidential candidate: Like the Energizer Bunny, he just keeps going and going. Like Old Man River, he keeps on rolling along. And he is held up as a pure example from the high school civics class in which we were taught that in America anyone can run for president.

He is also, like the majority of people who seek office, an also-ran.

For the purposes of this story, we are defining the perennial presidential candidate as someone who runs for — and loses — the race to the White House at least twice. And then runs again. The history books are full of them. So are today's political cycles.

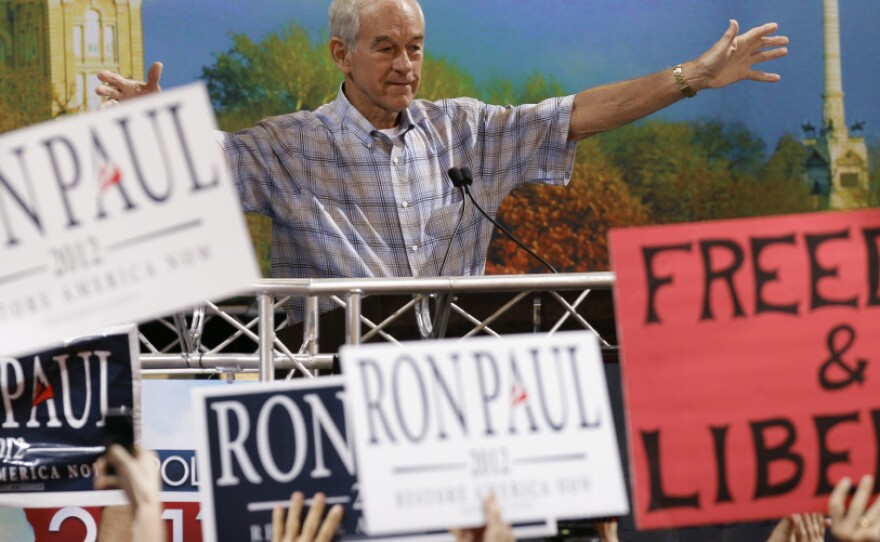

Among 2012 candidates: Rep. Ron Paul is seeking the presidency for the third time — and getting some traction. (A new poll from Suffolk University shows him running second to Mitt Romney in New Hampshire.) Andy Martin, an outspoken adversary of President Obama, has made multiple presidential runs.

And then there's "Average Joe" Schriner, a part-time house painter and handyman from Ohio who is making a bid as an independent candidate for the fourth time. "Running for president is a great way to get messages out," Schriner, 56, says from his home in Bluffton. Using the platform of a presidential run, Schriner travels the country — by motor home and sometimes bicycle — talking about close-to-his-heart issues, such as social justice, immigration and global warming.

"My ultimate goal is actually ... to win," Schriner says. "Seriously."

But Schriner — who, with his wife and three kids in tow, has logged more than 100,000 miles while campaigning over the past 12 years — takes strength from knowing that "each time people pick up on the ideas, it's as if we get a policy enacted long before we ever get to D.C."

Asked how he finances his campaigns, Schriner says he receives donations — about $37,500 in 2008 — and he puts a lot of his own money into the coffers. "I'm far from independently wealthy," he says. "I actually work in between campaign tours to put food on the table."

And asked how he feels about perennial candidates being viewed as also-rans or losers, Schriner says that because of his years on the campaign trail, "there are now more people doing more to help the urban poor here, to help the environment, to help curb crime, to help save the unborn, to help save the family farm, to help the immigrant, to help stem poverty in the Third World... Losers? By whose measure?"

Running As A Way Of Life

You may have heard of some perennial candidates. Harold Stassen, governor of Minnesota, president of the University of Pennsylvania and World War II veteran, ran for president so many times that reputable sources do not agree on a total. The New York Times and Encyclopaedia Britannica put it at nine. The Minnesota Historical Society says he ran 10 times.

Stassen did have some lasting influence, says historian and author David Pietrusza. "In 1952, Stassen helped swing the nomination to Dwight Eisenhower," Pietrusza says, adding, "He sort of looked like a younger Ike."

In 1956, Pietrusza says, Stassen "was part of a dump-Richard Nixon movement and may have hoped to replace Nixon as vice president and then become president in 1960. Nothing in that plan worked out."

Or maybe you have heard of Norman Thomas. Between 1928 and 1948, Thomas ran for president six times as the Socialist Party of America candidate. "He never thought he had a chance," says his great-granddaughter, Louisa Thomas, "but he'd argue with anyone who said so aloud. In 1932, during the Depression, it appeared there might be a chance to build something lasting. Time magazine even put him on the cover. But even then, there was disappointment: 885,000 votes, against FDR's nearly 23 million."

Though Thomas was a loser in elections, some of his progressive ideas such as unemployment insurance and a minimum wage were eventually folded into mainstream politics.

Louisa Thomas is author of the recently published Conscience: Two Soldiers, Two Pacifists, One Family — A Test of Will and Faith in World War I, a biography of Norman Thomas and his family. She says that Thomas' "final campaign was one he didn't want to run. In fact he declared that he had retired from candidacy. But who could take his place? The Socialists nominated him anyway, and he accepted. He feared that if he didn't run, Henry Wallace and the Communists would take over the mantle of the third party. And he still had things to say: He advocated the end of colonialism, civil rights and disarmament, among so much else. In the Atomic Age, he was worried that the world would destroy itself."

By the time Norman Thomas was an old man, Louisa Thomas says, "running had become a way of life, a habit. When he was old, crippled by arthritis, he met a woman who said, 'I remember you running for president when I was a little girl.' He responded, 'Madam, I've been running for president since I was a little boy.' "

Marginal Voices

Perennial candidate Ralph Nader, who recently called on Democrats to find someone to challenge President Obama in the 2012 primaries, has run for president a handful of times. Many people believe that Nader's Green Party candidacy in 2000 prevented Democrat Al Gore from defeating Republican George W. Bush. The controversy did not deter Nader. He ran again in 2004 and 2008. Nader, 77, told the Los Angeles Times that it is unlikely he will run again in the 2012 election.

Other famous perennial presidential candidates include William Jennings Bryan, Henry Clay, Alan Keyes and Lyndon LaRouche.

There are countless perennial presidential candidates you may never have heard of, like Earl Dodge, who ran as a temperance candidate six times between 1984 and 2004, and Montana Gov. Merrill K. Riddick who ran three times, beginning in 1976. Tennie Rogers of Oklahoma ran thrice — in 1992, 1996 and 2000; she lost.

Influence by perennial candidates on actual campaigns is rare, says Julian Zelizer, a presidential historian at Princeton University. "I am not sure perennial candidates have the kind of impact they think they do."

While there are some third-party candidates — like Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 — who transform a major-party agenda, or candidates who by some circumstance play a role in the outcome of a state's voting returns, like Nader in 2000, "in general," Zelizer says, "the major parties absorb some of their ideas, but most seem to be sideshows to the main event. The exceptions stand out. But the larger group of these candidates tends to be forgotten."

Perennial candidates, Zelizer adds, "do offer an opportunity for marginal voices in the political spectrum to organize, distribute literature and have a vote. But all in all they have not been major forces in elections."

Still, they run.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))