It should have been a quiet Election Day this year, but two states drew national attention at the polls.

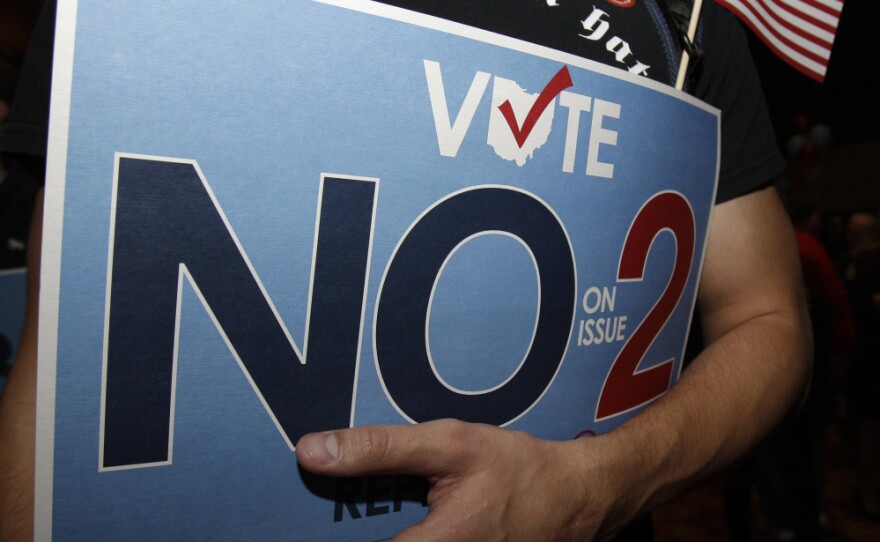

The proposed personhood amendment in Mississippi that would have effectively outlawed abortion was struck down. In Ohio, voters rejected a measure that would have restricted the rights of unions.

The outcomes suggest the electorate isn't completely in line with a party claiming an ideological mandate.

John Boccieri, a pilot and former congressman, knows about the quickly changing atmosphere of Washington. In 2008, he became the first Democratic congressman since 1950 of Ohio's 16th District, a moderate-to-swing district in northwest Ohio.

His district didn't vote for Barack Obama, and he tells Jacki Lyden, guest host of weekends on All Things Considered, that as soon as he got to Capitol Hill, he felt the political headwinds pick up.

"Almost immediately when the president had taken office, there seemed to be some sort of organized effort to try and build as many roadblocks as they could in front of moving any agenda of the president forward," Boccieri says.

Although Boccieri might not have filled his term with his personal political projects, he did support Obama's health care and energy legislation. Those became polarizing issues, and Boccieri found himself become a one-termer in 2010.

"I think that people from all parties, all corners, and all spectrums of Ohio believe that government is not working for them," he says. "And what they see in Washington, they see trench warfare, they see Democrats and Republicans digging in, not working together to solve our country's problems."

The Pendulum Swings

One year later, it's the Republicans getting burned after making big pushes for their agendas. But the results from Ohio shed some light on the meaning of a political victory. Although it was impressive Democrats were able to mobilize their base with a lot of help and money from unions, during an off-year election, it doesn't mean they can rest easy. Voters in the state also approved a proposal to prohibit people from being required to buy health insurance as part of the national health care overhaul.

"The fact that voters not only turned over the collective-bargaining reform, but also sent a message about individual mandate, means that simply trying to project a partisan or ideological read misses the larger story," says John Avlon, a senior political writer at Newsweek and The Daily Beast.

Avlon says that increased participation during a non-presidential election year is a good thing. But the idea of mandates from the voting booth might be past its prime.

"The idea of ... one party declaring an ideological mandate after they win a wave election is, at this point, totally discredited," he tells Lyden. "It is a willful misread of an election result."

It happened in 2006, when Democrats swept back to power in the House, Avlon says, and then the opposite happened in 2010 when Republicans came back and took away one-party rule in Washington. He says the same thing is happening in 2011.

After a big win, that misreading of the election results, Avlon says, is when a party's most ideological activists issue the party mandate. That, he says, is what immediately begins the pendulum swinging the other direction.

"We are in a cycle of overreach and backlash in our politics," he says.

Morris Fiorina, a professor of political science and a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, agrees.

Democratic and Republican candidates for president build their base from the left and right, respectively, Fiorina says. But in order to win, they have to get the center. But that all changes once a candidate takes office.

"In the case of Obama administration ... the pressures (from the left) were to act on things like cap and trade, stop global warming [and] health care," Fiorina says. "But those were not the priorities of the country. The priorities ... were jobs and the economy."

This causes an administration to get out of touch with the bulk of the population, Fiorina says. The overreach is just that: acting in a way that causes an administration to lose the marginal members of their electoral coalition, he says.

The People's Mandate

Avlon says that the center has been sending a consistent message: It doesn't like it when one party has unified control over Washington and it wants some form of fiscal responsibility.

"What's interesting about this particular time in American politics is that, in the past, divided government has not meant dysfunctional government," Avlon says. "That is a key difference."

That "dysfunctional" government is what perpetuates the swing of the pendulum and one of the reasons it is moving so quickly, he says.

So Americans' preference for government from the center might be what's pushing back on government from the extremes.

Fiorina says you'd have to go back to the late 19th century to find comparable volatility and instability in Congress. A finger can be pointed to the leadership in both parties, he says, as to why this is happening now.

"Parties like to think to think if they won, they have a mandate. The American people don't have (ideological) mandates," Fiorina says. "The mandate is to solve problems and to move the country forward. If you don't do it to the satisfaction of the electorate, they turn you out."

Instead of paying attention to the seemingly large swings from party to party, perhaps politicians should look a little more closely at the results. What happened in Ohio and Mississippi, Avlon says, is happening in the minds of the voter and their sense of limits in America, a good lesson for next Election Day.

"There's also a heartening sense ... of discernment that comes with swing voters who are decidedly saying that they are not going to walk in lockstep blindly with one party or one ideology," he says.

That, he says, is a lesson beneath this election as we look toward 2012.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))