In the face of mounting public pressure to do something about the worsening homelessness crisis, San Diego leaders are pushing a proposal that would make it illegal to live in a tent virtually anywhere in city limits.

Some have called it cruel and inhumane, urging the city to instead pour resources into housing and evidence-based approaches. Others have praised the city for taking action against the growth of tent encampments, saying they’re sick and tired of seeing people have sex, defecate and use drugs outside homes, businesses and schools.

There’s one glaring problem, though: San Diego doesn’t have nearly enough space in homeless shelters for those who need it. Attorneys say that would make enforcement illegal.

City staff members insist they are committed to expanding shelter capacity, and can offer parking and camp sites within a matter of weeks. Mayor Todd Gloria’s “Getting it Done” budget proposal, which he announced last week, calls for $5 million to continue expansion efforts into next year.

But that’s less than what it costs to run a 270-bed shelter downtown.

About 2,500 San Diegans are living on sidewalks and in canyons and riverbeds — far more than the 1,800 shelter beds that were 97% full earlier this week.

Gloria’s spokesperson did not respond to questions about his budget proposal as of Thursday morning.

Top city officials have railed against unhoused folks who refuse to accept shelter, but in reality, many people are turned away. One outreach team said they have to turn away dozens every day, and even the most eager and persistent people are forced to wait hours, days or even weeks to get in.

On any given day, emergency shelters throughout the city only have room for about 25 unhoused residents, and that availability can sometimes vanish in a matter of hours.

It took 50-year-old Kenneth “Tony” Garcia a week of calling, waiting and wandering around City Hall downtown before an outreach team found a place for him in a shelter. He recently lost his housing due to family issues, he said.

“I just got into a state of depression and I kind of walked around in a daze, not even eating,” Garcia said in an interview Tuesday on his way to the shelter. “And now I feel like there’s something to look forward to again. Now I’ve got hope again.”

Backed by Gloria, Councilmember Stephen Whitburn announced the proposed camping ban last month to combat the growth of tents in his downtown district. It’s a matter of public health and safety, he said, and the city needs a new, straightforward law to address it.

The proposal comes at a time when two local attorneys with decades of experience fighting San Diego’s treatment of unhoused people are challenging the constitutionality of another law that police have increasingly used to break up tent encampments. The city law is called encroachment and was originally intended to prohibit trash cans from blocking a sidewalk.

At the same time, homelessness in San Diego has become more visible than ever before. More than three times as many people are living on downtown sidewalks than before the pandemic, and the number of San Diegans who lose housing is outpacing the number that can be helped.

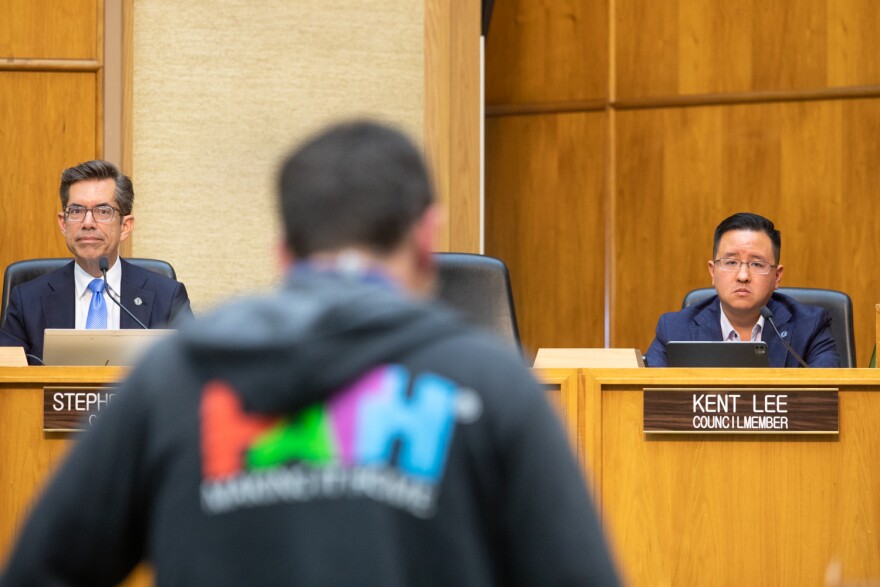

After taking heat from nearly every corner of San Diego last week, the city’s Land Use and Housing Committee agreed to move the proposed camping ban to the full City Council, but councilmembers told staff to be ready to answer questions on shelter capacity and enforcement. A vote could come as early as next month.

“I think it’s abundantly clear that there are many, many unanswered questions and it leaves me concerned that if this were to be adopted, we would be rushing through this, not only without addressing the actual issues at hand, but rather possibly exacerbating them,” said City Councilmember Kent Lee, the only person on the four-member committee who voted against the proposal.

Anger on all sides

About 140 deeply divided residents attended the meeting in person or virtually and used all 60 seconds given to them to speak passionately about Whitburn’s proposal. Some spewed animus and invective either directly at him and the committee or toward unhoused people who have nowhere to live but the sidewalk.

Property owners, school officials and parents described traumatic experiences from living and working near encampments, including threats or acts of violence, open drug use and overall deplorable conditions.

Cookie Serrano, a member of an East Village community organization, said downtown residents no longer feel safe and businesses are closing down or moving away.

“We are frequently chased by angry, homeless people, carrying around weapons, such as guns, machetes, knives, boards, arrows, hammers, screwdrivers and bricks, trying to scare and intimidate us, to steal from us or to use these to destroy private property,” she told the committee.

The principal of a downtown elementary school, Fernando Hernandez, said committee members would have no idea what children experience on a daily basis just driving by.

“They have seen people having sex; they have seen men punch women in the face and leave them bloody, and then they come to school and they talk to us about it,” Hernandez said. “They have seen individuals pumping needles into their arms and come to us about it. And then we have to spend time talking to our students to de-escalate them and get them ready to learn reading, writing and math.”

On the other hand, many derided elected officials for even considering the camping ban. Advocates, researchers and local leaders tasked with solving homelessness urged the committee to reject the proposal and pointed to studies showing this approach only makes homelessness worse and more costly.

One speaker called out the proposal for being politically motivated.

“The committee members who sit on the dais above you know this proposal is a political move to placate privileged, housed constituents and their wealthy donors who don’t want to see poverty,” said Janis Wilds. “They hope it will get them re-elected.”

Megan Welsh Carroll, a San Diego State researcher who just last month presented findings to the city and recommended taking police out of all homelessness related issues, said this proposal would make it illegal for unhoused people to stay near 331 of the city’s 354 public restrooms.

“In our effort and desire to do something about our housing crisis, we are on the verge of doing the wrong thing,” Welsh Carroll said. “This ordinance will not stop homelessness in San Diego, it will simply push unhoused San Diegans further away from outreach and services they desperately need. People will stay in evermore remote areas of our riverbed and canyons.”

After public comment, Whitburn and city staff insisted this proposal would only clarify existing laws that ban encampments. Police officers would enforce this ban the same way they have with the trash can law — offering shelter each time they encounter someone, elevating enforcement after each refusal from a warning to citation to jail. A person would be arrested after they’ve refused shelter at least four times.

But other members of the committee pressed staff on enforcement: Courts have ruled that cities cannot criminalize people for carrying out life-sustaining activities, such as sleeping or sheltering, when there is no other option. So how can the city enforce this when the shelter system remains over 90% occupied?

San Diego’s Chief Operating Officer, Eric Dargan, said officials are committed to opening a variety of shelter options, including parking spaces for those living in vehicles and camp sites for those in tents, within the next 60 days. But as long as one shelter bed is open, police can enforce the law citywide.

Officers find out every morning how many beds are available, said Chief David Nisleit. Once they encounter someone who wants shelter, that’s when they make the call to see if it’s still available.

“If I can get one or five or 10 or 100 people off of (the streets),” Nisleit said, “we shouldn’t worry about the whole 1,700 people that are (currently experiencing homelessness downtown).”

Waiting a lifetime

On Tuesday morning, Craig Thomas and Ali Herrera tried to help fill roughly two dozen shelter beds citywide.

As Alpha Project homeless outreach workers, they show up at known encampments in designated areas to build trust and relationships with folks who are experiencing homelessness.

As their van moved about the city under clouds and a light rainfall, Thomas’s cell phone rang every few minutes. On the other end was a voice asking for help.

Thomas took down the caller’s information — from age to disability to criminal background — and submitted it into a homeless management system. From there, it’s a waiting game. Intake coordinators on the other end review all of that information and find a shelter that best suits the client’s needs.

“The issue with that is it usually takes two to three hours,” Thomas said. “And if you’re familiar with the homeless lifestyle, two to three hours is damn near a lifetime.”

Someone struggling to meet the most basic needs — food, water and shelter — could move on to other pressing issues. And some lose trust in the system.

“That’s what makes it more difficult, when you have a client that you’re working with for months and they keep telling you, ‘no, no, no,’ and you finally have them at that moment where they’re saying ‘yeah,’ you need to get them there like that,” Herrera said with a snap of her fingers, “because you give them an hour, you give them two hours, they’re going to change their minds. That’s it.”

The outreach workers said they end up losing track of a lot more folks than they can actually help.

Add police officers to the mix and it makes the job even harder. Enforcement efforts and cleanups require people to stay mobile, which can cause them to lose important documents that are necessary for getting into housing.

And that’s how people lose motivation.

But despite those challenges, Thomas said he doesn’t stop taking calls until it’s time for bed. Because he knows exactly what it means to reach out for help.

“When I was on the street,” he said, “having that voice on the other end of the phone actually just helped me get comfortable with the fact that somebody’s actually there to help me.”

It also takes persistence to find shelter in San Diego. Garcia, the 50-year-old man who recently became unhoused due to issues at home, called every day for a week trying to get in. On Tuesday, he’d been calling Thomas for about an hour.

Riding in the van on his way to a shelter, he said he most looked forward to getting cleaned up for a fresh start.

“This is not me, I just feel icky,” he said, referring to how dirty he got while living on the sidewalk. “As soon as I can get on clean clothes, shave, take a shower and all that good stuff, I can be back to making something happen.”

Moses Miramontes, 46, has spent the past six months in an Alpha Project shelter. It took persistence to find his shelter bed also, and once he got it, he felt a renewed sense of motivation.

After some badgering phone calls last October, the outreach worker eventually said if he wanted a bed, he needed to go right away.

“I dropped everything I had and I just brought what I could, and that was it,” Miramontes said. “I jumped in the van and they brought me here. I was happy to get off the streets because of the real bad traumatic experience I had.”

He said he’s suffered more than a dozen attacks living on the streets for the past four years, including what he described as a near fatal stabbing and a separate incident that ended with a cinder block crashing over the the top of his head.

“It’s a whole different way of life to where it’s nothing but survival,” Miramontes said. “Like, as in the jungle.”

Now he’s had an opportunity to get his feet underneath him, focus on his sobriety as well as securing income and housing. His family has started coming back into his life again, giving him what he considers his second and final chance.

It’s almost like when Rocky Balboa faced off against Apollo Creed or Mr. T, he said.

“Eye of the tiger. This time, we’re going to actually fulfill these promises. We’re going to do what we said.”