San Diego police made 141 curfew arrests last year, according to their own records, mostly of Black and Latino youth. They detain the children, call their parents and return them home or to the police station for pick up. According to city law, children under 18 can’t be out without an adult between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m., with few exceptions.

An SDPD spokesperson said they enforce curfew to keep children safe during late-night hours and make it less likely that they’ll commit crime. But research is almost unanimous — it’s not effective.

“Curfews function as devices to waste police time taking law-abiding youth off the street,” said Mike Males, a senior researcher for the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. “Creating antagonistic relationships between police and youth and really not accomplishing anything.”

That research doesn’t seem to shape the policy of San Diego police, who continue to enforce curfew long after other cities in California stopped. At one point, the city accounted for 40% of all curfew arrests in California.

While the number of curfew arrests has gone down in recent years, racial disparities in those arrests have increased. Black and Latino youth make up more than three-fourths of the arrests in San Diego. Nearly one-third of the arrests are made in majority-minority neighborhoods including Otay Mesa, Logan Heights, City Heights and Mount Hope.

The SDPD spokesperson said by email that “there is no simple explanation” for that disparity.

“They can be the result of radio calls, community caretaking, and proactive contacts,” the spokesperson said. “Our officers take each case seriously and treat all children with care regardless of their situation.”

Males said racial discrimination is the point.

“A lot of this is just, frankly, racial intent,” he said. “It's to get Black and Latino youth off the streets, out of the public where they're frightening mostly white patrons of gentrifying areas or suburbs.”

Curfew law can also bias along class lines — children from lower-income families often don’t have the option to hang out in cars like children from wealthier families, Males added.

He said the intent is misdirected; teens actually have a lower-than-average crime rate, and it’s been going down in recent decades.

“If we’re going to curfew anybody, yeah, it should be people in their 30s,” he joked. “But a curfew wouldn’t help there either.”

Males said in more than 99% of the many hundreds of curfew arrests they studied, the youth were not doing anything wrong — just things like playing basketball in the park or coming back from the movies.

The consequences of curfew enforcement

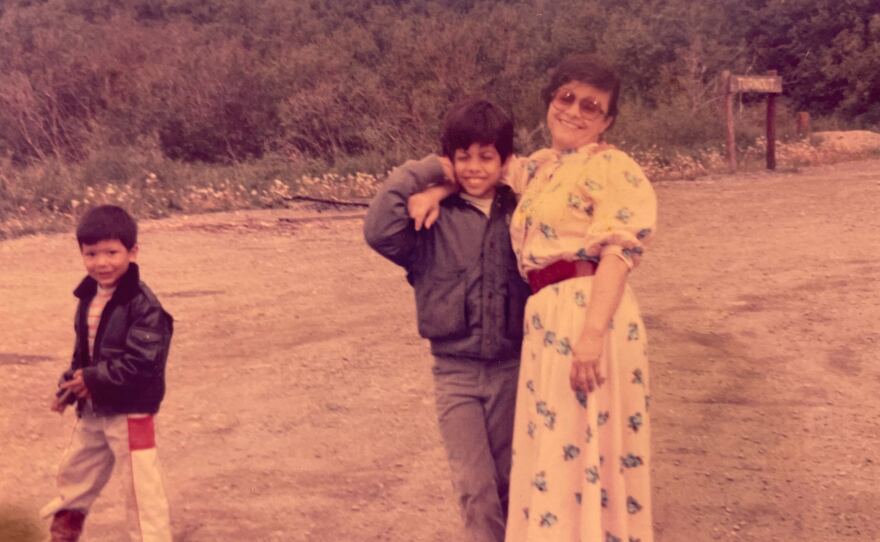

Arthur Soriano’s first arrest was for violating San Diego’s curfew as a teenager in the early '90s. He said it was the beginning of his school-to-prison pipeline.

These were the years when politicians, including then-Sen. Joe Biden, promised to be tough on crime to stop “super-predators” — the myth that more and more youth were committing violence without remorse.

Soriano said City Heights youth feared the police, who he said only came into the neighborhood for things like curfew sweeps and immigration raids. (There was only one exception, an officer kids called “Pac-Man” whom Soriano still remembers decades later for his respectful communication.) So when they saw police officers, they ran.

At the time, he said, the community had a lot of trauma and few resources.

“Everyone was fighting for their lives,” he said.

Soriano was a latchkey kid, raised by a single mother who worked two jobs cleaning homes. Without other family in the area, he sought out people to validate him.

“I needed a way out,” he said. “And how I found my way out was becoming part of gangs.”

At the time of his curfew arrest, he said he was more of a “gang wannabe.” At night, his friends liked to gather in the Qwik-Korner convenience store parking lot. Most times, he said, they weren’t doing anything wrong.

“We were just hanging out and talking smack to each other and laughing and giggling,” he said.

But it didn’t matter.

The police grabbed Soriano for curfew, and they discovered he had a stolen bike, too.

He was sent to juvenile hall — just for a few days, before being put on probation. But he said it was the start of a cycle. The demands of probation overwhelmed him, so he ran.

“For most kids, our way of solving it was just running, running until we would get caught,” he said.

Soriano said those interactions with police fed into his identity as a gang member. He would eventually go to prison for 23 years. He’s been out for the last 11, and now works with youth caught in the same system.

“Hope, right?” he said. “I’m a beacon of that now.”

Males asked why San Diego police still enforce curfew.

“If somebody's not doing anything wrong, why are the police interested in them?” he said. “And if they are doing something wrong, then they don't have to arrest them for curfew. They can arrest them for that. So I really don't understand the policy.”

Even without added punishment, Males said enforcing curfew is not harmless. It perpetuates negative interactions with the police, primarily between police and youth of color.

And, he said, research shows youth being in public during curfew hours actually helps reduce crime. Less empty streets, more witnesses.

Soriano suggested an alternative to curfew: youth drop-in centers that could be open late night, year-round.

“We need them safe spaces in these communities that are marginalized,” he said.

Soriano helped run extended youth programs during the summer and said he was surprised by the demand.

“We were like, ‘Man, these kids, they're not going to stay with us for five, six hours,’ right?” he said. “They're going to want to go back home and get into what kids get into. And no, like clockwork, from 12 to 6.”

He had another idea, too — staffing parks at night to provide another adult presence besides police. Bring the resources to where the kids are hanging out anyway.

Youth drop-in centers were voted down in this year’s city budget. City council members will reexamine the budget next spring.