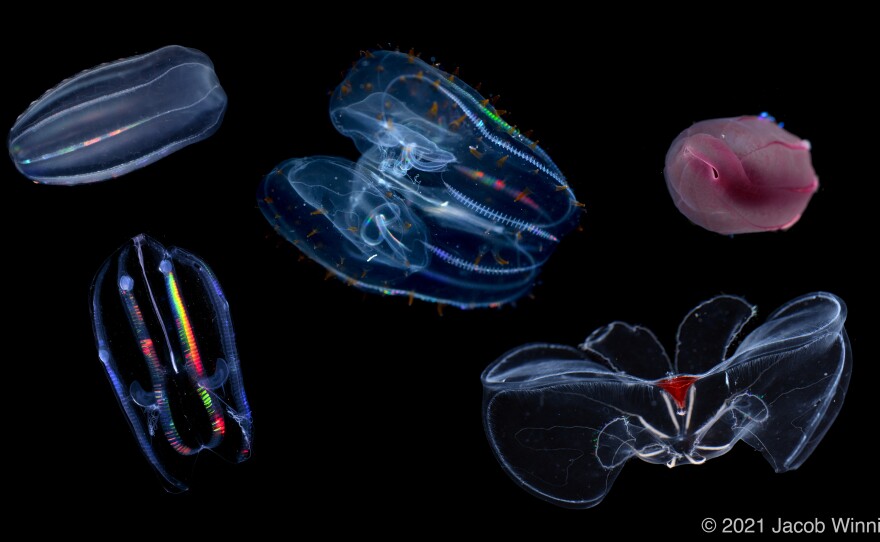

They’re called comb jellies though they’re not jellyfish. And they are beautiful when exposed to the light.

But where some of them live, 8,000 meters beneath the sea, there is no light and they have to adapt to the tremendous pressure of all that ocean water.

“And it’s known that pressure has relatively strong effects on the behavior and the packing of lipid molecules. These greasy molecules that make up cell membranes,” said Itay Budin, a biochemistry professor at UC San Diego.

Budin partnered with other scientists on a paper published in the journal Science that showed these creatures, also called ctenophores, evolved to have lipids that adapt to the deep sea.

Think of cell membranes as plastic bags that contain and enclose cells. They also contain and separate other elements within the cells. Lipids line up to form cell membranes. But if you look really close you see they have different molecular shapes and their shapes change under pressure.

“So what I mean by that is that some lipids, they look like this diet coke can,” Budin said, holding up the can.

“They’re nice cylinders. So you can imagine those cylinders, when you have many of them – I drink a lot of diet coke – they pack together into a flat membrane.”

He said comb jellies also have lipids that are triangular, like traffic cones. But what if they’re under pressure in the deep sea?

“So what pressure does is it will actually compress those chains so that they bunch up next to each other. So if you have a lipid that looks like a traffic cone, at huge pressure it will look like a coke can,” Budin said.

Jacob Winnikoff is a deep sea biochemist at Harvard who partnered with Budin on the study.

He points out lipids that make up cell membranes can't all be coke cans. For certain things to pass in and out of them you need some lipids that are like the traffic cone or, if you play badminton, a shuttlecock.

“So what we see in the deep sea comb jellies is they have a different makeup of lipids. They have rearranged some of the atoms in these lipid molecules so that even under pressure they’re still shuttlecock shaped,” Winznikoff said.

If a person were placed in that deep sea environment, they would be crushed. If a deep sea comb jelly were placed in a low-pressure environment, it would disintegrate, given the evolution of their cell membranes.

These lipids with their exaggerated shapes are called plasmalogens and they’re found not just at the bottom of the sea.

“So it turns out that some of the lipids that are most abundant in the deep-sea species, they also show up in our bodies. And they show up specifically in the nervous system in the greatest abundance,” Winnikoff said.

What are they doing in our bodies, if not responding to high pressure? That’s a subject for future study.