People who think they didn't get sick from a nationwide meningitis outbreak caused by contaminated steroid injections used to treat back pain may want to think again.

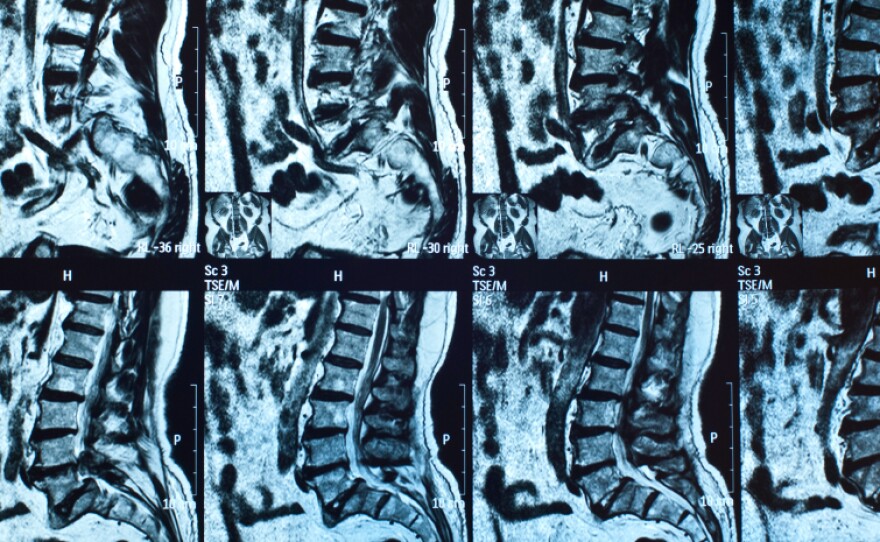

Doctors at hospitals in Michigan did MRI scans of people who had been given tainted injections but didn't report symptoms of meningitis afterwards.

About 20 percent of the 172 people tested had suspicious-looking MRIs, and 17 ended up needing surgery to treat fungal infections in or around the spine.

The patients had gotten steroid injections about three months before the MRI, in mid to late 2012.

Even though some of the people had increased back pain and other problems after the tainted injection, quite a few hadn't gone to the doctor to report the symptoms before the researchers contacted them about getting an MRI.

The researchers think that's partly because people weren't able to tell if the pain was caused by the back problems that led them to get the injection, or from something new.

It may also be because the first people who got sick from the contaminated shots came down with meningitis, an inflammation of the tissue that wraps the brain. It's the kind of life-threatening illness that's hard to ignore. At least 23 people died.

As the number of meningitis cases waned, and people started coming down with spinal infections instead. It's as if the meningitis cases were on a fast boil, and the spinal infections were simmering on a back burner.

This screening method isn't perfect: 17 percent of the patients screened had equivocal MRIs.

But screening with MRI may be a better option than treating all exposed people with high doses of antifungal medications, according to an accompanying editorial. Toxic effects of treatment include altered mental states, hallucinations, and liver damage.

The Food and Drug Administration has warned people who may have been exposed to medicines produced at the New England Compounding Center after May 21, 2012, to be alert for headaches fevers, chills, and other symptoms.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends MRIs for people who received contaminated injections and who had symptoms at or near the injection site. The company produced about 1,200 different drugs, most of which were injectables.

But the study authors, who work at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, the Veterans Affairs An Arbor Healthcare System, and the University of Michican Medical School, think that it would be better to screen all patients at risk, whether they've got symptoms or not.

The results were reported in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association.

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.