Many of us get confused by claims of how much the risk of a heart attack, for example, might be reduced by taking medicine for it. And doctors can get confused, too.

Just ask Karen Sepucha. She runs the Health Decisions Sciences Center at Boston's Massachusetts General Hospital. A few years ago she surveyed primary care physicians, and asked how confident they were in their ability to talk about numbers and probabilities with patients.

"What we found surprised us a little bit," Sepucha says. "Only about 20 percent of the physicians said they were very comfortable using numbers and explaining probabilities to patients."

Doctors, including Leigh Simmons, typically prefer words. Simmons is an internist and part of a group practice that provides primary care at Mass General. "As doctors we tend to often use words like, 'very small risk,' 'very unlikely,' 'very rare,' 'very likely,' 'high risk,' " she says.

But those words can be unclear to a patient.

"People may hear 'small risk,' and what they hear is very different from what I've got in my mind," she says. "Or what's a very small risk to me, it's a very big deal to you if it's happened to a family member."

Simmons and her colleagues are working on ways to involve their patients in shared decision-making. The initiative at Mass General gives patients online, written and visual information to help them. One of the goals is to make risk understandable — bridging the gap between percent probabilities and words.

Dots Help Decide

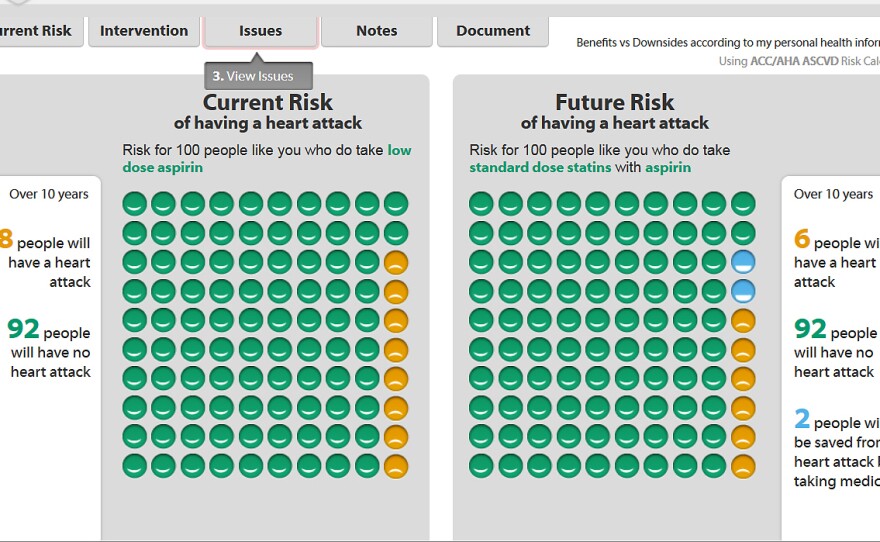

Simmons tried it with her patient Joe Bianco, 60, when talking over his risk for heart disease a few weeks ago. Rather than just using a number to tell him his risk for a heart attack, she made it visual with this statin/aspirin decision aid calculator, developed by the Mayo Clinic.

The calculator displays 100 green dots arranged in a 10-by-10 grid. Each has a little smile on it and symbolizes a person. Once a patient's information is entered, some of the green dots turn yellow and some smiles may turn upside down into frowns, indicating in the next 10 years, how many people are expected to have a heart attack.

When Bianco's profile is submitted, 12 dots turn yellow and 88 remain green — meaning 12 percent of men like him will have a heart attack within 10 years. "It looks like my chances are slim," he says.

Bianco had decided earlier not to take a cholesterol-lowering statin medicine to lower his risk of a heart attack. The dozen frowning yellow dots don't change his mind.

Next, Simmons enters another factor into the online calculator. What if all 100 men fitting Bianco's profile take a statin drug every day for the next ten years?

The number of yellow dots on the screen — the percent who will have a heart attack — changes for the better.

"That number goes down to seven — so five people are saved from a heart attack by taking a medication," Simmons says. "Some people look at that and say, 'Well that's almost cutting the risk in half.' Other people say, 'Well, that's still 88 people who didn't benefit either way. And only five who had a benefit.'"

For Bianco, seeing the graphic validated his previous decision not to take medicine. And for Simmons, as a doctor, it's made that conversation easier.

Numbers Still Valuable

But the graphics and words alone don't work for everyone. At Mass General's orthopedics department, Jim Westberg of Nashua, N.H., has come to see surgeon Andy Freiberg, who is in charge of hips and knees.

Westberg is very active at 59. He hikes, swims, skis and rock climbs when he's not at work, selling 3-D printers. He wants a hip replacement and in the course of examining him, his doctor cites some numbers.

"Your risk of infection is probably under 1 percent, probably half a percent," Freiberg tells him.

That the risk is less than 1 percent doesn't deter Westberg. Before his appointment, he had received a shared decision-making packet that included a booklet and a DVD, all about hip replacement. He also did some other research and — just as importantly — talked to people he knew who had had the surgery and were thrilled with the outcome.

For him, Westerberg says, the numbers and percent probabilities are still valuable.

"I think they're fairly important because I actually have an engineering degree," Westerberg says. "I have a technical background so maybe I'm a little biased, but numbers do mean something to me. The risk we talked about, half of 1 percent, really doesn't concern me that much."

What Is 'Very Common'?

The Food and Drug Administration also likes numbers and urges drug companies to give numerical values for risk — and to avoid using vague terms such as "rare, infrequent and frequent."

But the European Medicines Agency (a part of the European Union) has matched a scale of terms — very common, common, uncommon, rare and very rare — with numerical definitions for each of those five levels of frequency.

So, what percent of cases qualified for the top level "very common" side effect? You might think over 50 percent, but according to those EU definitions, a side effect is "very common" if occurs in more than 10 percent of cases.

And if a drug label says that a particular side effect was "very rare"? That means it occurs in fewer than one in every 10,000 cases.

This is part four of an All Things Considered series on Risk and Reason.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/