Anybody who has ever seen a drug advertisement or talked over the pros and cons of a medicine with a doctor can be forgiven for being confused.

Sorting out the risks and benefits of taking a medicine can be complicated even for professionals.

This spring, the Institute of Medicine convened a workshop with the Food and Drug Administration. The topic: How best to communicate to doctors and patients the uncertainty in the assessment of benefits and risks of pharmaceuticals.

The FDA not only approves drugs, it also approves the prescribing instructions that come along with them. For some drugs, the wad of paper filled with fine print about the risks and benefits of using the drug is accompanied by a medication guide that is supposed to summarize the main points.

During one question-and-answer session, Dr. Robert Temple of the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, acknowledged that those guides are full of information. "But it's remarkably nonquantitative for the most part," he said. "And I think we should try to think about whether there are quantitative ways of presenting that stuff."

He then referred to Drs. Steven Woloshin and Lisa Schwartz, two of his fellow panelists, who have said it's possible to pull that off.

The husband-and-wife team from Dartmouth are on a decade-long mission. They have been pushing the FDA to get useful and readable quantitative data about drugs to doctors and their patients.

Schwartz and Woloshin have designed a format they call a drug facts box. It shows the gist of what they say is buried in all the fine print: How does the drug compare to a placebo?

That's in contrast to what usually happens, Schwartz says. "The prescribing info is written by industry, and then negotiated with FDA, and then FDA ultimately approves it. And we have documented examples where important info — like how well the drug works — is not in the label."

This drives Schwartz and Woloshin crazy.

Better Than A Sugar Pill

So, here's their experiment: They showed people ads for two competing heartburn drugs, one plainly more effective than the other.

They also showed people two of their drug facts boxes, one for each of those two heartburn drugs, showing how each drug fared against a placebo (a sugar pill) in testing.

"When the people are presented with the standard information they see — like a drug ad — about 30 percent of people chose the better drug," Woloshin says. "But when we showed them information in the drug facts box form, 68 percent of people were able to choose the objectively better drug. So that's a really dramatic improvement. It just shows you that if you show people information in a way that's understandable, they can use it, and it can improve their decision."

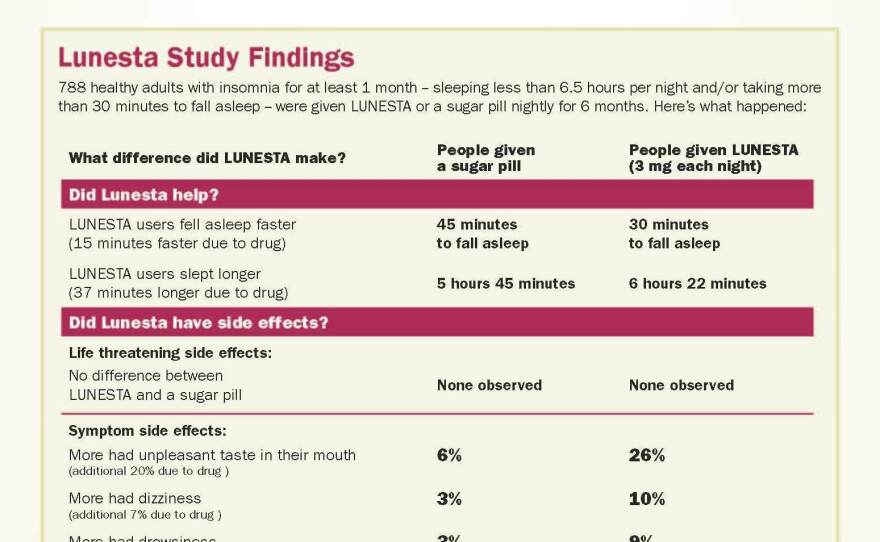

Using FDA data, Woloshin and Schwartz developed a drug facts box for the sleep aid Lunesta.

Two columns compare people with insomnia who took Lunesta and people with insomnia who, unknowingly, took a sugar pill.

The results? Those who used Lunesta took 30 minutes to fall asleep. Those who got a sugar pill took 45 minutes — a difference of 15 minutes. Those who took Lunesta stayed asleep 37 minutes longer than those who took a sugar pill.

Woloshin and Schwartz say some people might consider those benefits worth taking the drug, and some might not.

"That's the whole point of the drugs facts box," Woloshin says, "to let people look at the evidence and come to their own judgments. But you can't make those judgments without the facts.

He and Schwartz believe passionately in the numeracy of patients. They say we can handle numbers, like percents. It's just that too often we're given incomplete or misleading information.

How Good A Deal Is That Sale?

For example, a claim that some drug reduces the likelihood of a particular disease by 50 percent can be misleading.

Woloshin explains why. "If you heard about a sale, and it said 50 percent off, would you travel a great distance to go to the sale? Well, you might if it was on things that are really expensive, like a flat-screen TV or something," he says. "But what if the thing that was on sale was gum, and you save only a couple of cents? So when you hear 50 percent reduction, you have to ask 50 percent of what?"

The doctors' dream is to get those drug facts boxes into health systems and electronic medical records, so that doctors and patients can study the information and decide what's best before the drug is prescribed.

"What we hope is that the box will encourage people to take drugs that are effective and that work, and discourage people from taking drugs that don't work or are just harmful," Woloshin says. "And also that just having this information in front of people will stimulate better drug research, because drug companies realize people are paying attention and looking at these numbers — and then we'd have a better quality of drug trials."

Woloshin and Schwartz say medical information should be as quantitative as other information. And we digest quantitative data all the time.

"If you were reporting on an election, you wouldn't say Obama won by a little," he says. "You'd give the numbers. If you were reporting sports scores, you wouldn't say the Celtics, won, hopefully won, by a bit. You'd give the score."

Why should health care be different?

He and Schwartz are convinced that we can understand risk described by numbers, provided the numbers are clearly and honestly presented.

They have been lobbying the FDA to develop drug facts boxes, but say that seems unlikely. So they started their own company to do it — Informulary. It's funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which also supports NPR.

This is the final part of an All Things Considered series on Risk and Reason.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/