TOM FUDGE: Our top story on Midday Edition, this weekend's northern California was rattled by a 6.0 earthquake that have nothing to do with the drought, right? Actually, a possible increase in seismic activity is one of the things that can result from the massive loss of groundwater we have seen since the Western drought began. An estimated loss of 63,000,000,000,000 gallons of water in the West, mostly groundwater, was one finding in a study done by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. In fact, the loss of water and it's enormous weight has actually caused the ground to rise more than half an inch in the California mountains. Joining me to talk about the study and the phenomenon are Adrian Borsa and Randy Hanson. Thank you for coming in. Adrian, your study says that the American West has lost 63,000,000,000,000 gallons of water as a result of the drought, how do you figure that? ADRIAN BORSA: We start with the observed changes in vertical motion of GPS and what we saw was an uplift of several millimeters, which does not sound like a lot, but in fact is quite a large signal. We can then take that, these changes in vertical motion over a large number of GPS stations, and perform an inversion, which gives us an idea of how much load that there has to be to account for that change. TOM FUDGE: And you figured 63,000,000,000,000 gallons of water, is that all groundwater or water from reservoirs and lakes? ADRIAN BORSA: It would be both, and that this method we cannot tell which component of water we're looking at. TOM FUDGE: You said the earth is like a rubber block, what do you mean by that? ADRIAN BORSA: We don't think of rock as elastic, but it is, especially at longer distances. If you press on the rubber block with your finger, you would depress the rock, that is the same thing that the earth does when you put a water load on it, and in this case we're taking off the water load and the earth is rebounding. Over long distances and with GPS, you can see the change. TOM FUDGE: With the instruments that you used, what are those supposed to be used for? ADRIAN BORSA: They were put in the Plate Boundary Observatory Network to look at crustal deformation due to tectonic change, so we are sitting at this very active place on our surface of the San Andreas Fault along the Pacific and North American plates, this network was built to study how these tectonic motions cause the Earth's surface change. TOM FUDGE: You are putting them into measure earthquakes? ADRIAN BORSA: It's not actually in place, but it tells you something about seismic hazards. There are seismic networks to measure earthquakes, in other words about the background stressing, how these faults change and evolve due to tectonic forces. TOM FUDGE: What part of the West we see the greatest uplift? ADRIAN BORSA: We saw its greatest in the Sierra Nevadas and the California coastal ranges. We surmise the reason is that those are the areas that get the most water. In a drought, they lose the most water, percentagewise. TOM FUDGE: And the mountains, because of the snow? ADRIAN BORSA: The snowpack did change, and you do see the effect their in the snowpack as well. TOM FUDGE: Getting back to the subject of earthquakes, which I mentioned at the top of the show, is this water created greater likelihood of earthquakes? ADRIAN BORSA: A study did show increased seismicity, we did a similar tessellation and did not see significant changes on the stresses on the San Andreas fault, this is not the last word, but we did not see anything. TOM FUDGE: Why would a lack of water cause more earthquakes? What is the theory behind that? I know that you did not come to that conclusion, but why would we think that? ADRIAN BORSA: If you imagine uplift occurring in one area and not another, that would create differential stresses that could activate or push some faults closer towards failure, and an earthquake. TOM FUDGE: Randy, anything you would like to say about the subject of earthquakes and groundwater? RANDY HANSON: The study is great, it really looks at the deformation aspects, but really the thing that is interesting is the water deficit that has been captivated here, that is really important. They excluded some of the valleys, we work in the valleys a lot and the deformation is over the same drought period, and the Central Valley it was 100 times or more. TOM FUDGE: You used the word deformation, what do you mean by that? RANDY HANSON: That is the lines surface rising or falling, so land subsidence would be one form of the land falling in places we see like the Central Valley. TOM FUDGE: Tell us more about what you think the study that your colleague was involved with, what do you think about that, were you surprised to see the amount of water? With the new thing for you? RANDY HANSON: We actually used the PBL site ourselves, I was not surprised, it was a fair amount of water. Put in the context of where it is occurring, it's a significant percentage of water locally, in the Sierra Nevadas and the coast range. But really, the idea that we are getting 4 mm up to 15 mm of a prize is not surprising at all, it's great that they are using another line of data, this particular type of data really has not been cultivated yet by a variety of researchers. It originally had one purpose, but I think people are finding other purposes for this kind of data. It's exciting to see them use it as well as some of the applications we have had. TOM FUDGE: Is this something that we have seen before, or is this the first time we've had this technology in place to see this uplifting land? ADRIAN BORSA: The GPS stations that we're using, the network was built in 2005, prior to that, there were stations in Southern California. You would be able, in fact we did see changes, in the vertical motions. It was hard to interpret them, but when you have an entire Western United States to cover, it's much easier to draw inferences about what we're seeing. TOM FUDGE: When we look at this lack of groundwater, how much of this is caused by the drought, and how much of it is caused by water agencies pumping water out of the ground? Do you want to take a shot at that, Adrian? ADRIAN BORSA: It's difficult for me to say how much of it is due to which component, I will say that there is a large seasonal cycle, seasonal component in the GPS. We have removed that, but winter rains caused the earth to subside and in the summer, drying costs it to rebound. That has been well known, that was not a surprise. Without the drought, we would not have looked for other drought like effects, but in terms of where the water is coming from, we cannot say, I think that is the realm of the hydrologists. TOM FUDGE: Well, we have a hydrologist in the room, so I will ask Randy, farmers in the Central Valley rely on groundwater for farming, I guess it's also extracted to fill aquifers. K talk us through that? RANDY HANSON: The whole Central Valley irrigation system was built up around dams, and they really relied on the surface water, and then they exceeded that resource, and went back to pumping groundwater, in which they originally brought in surface water to stop land subsidence. About a third of the water that was pumped from the 20s through the 60s and 70s was actually from land subsidence, that was a one-shot deal, they got that water only once. They brought in surface water, exceeded the surface waters, with the drought and climate change and everything else going on, they're having a lot of pumping, and they are re-initiating land subsidence in these areas. TOM FUDGE: As a result of water policies of the last few decades, we have a lot of water in reservoirs and less water in the ground, that's what you're saying? RANDY HANSON: They are depleting the water in the ground, yes. TOM FUDGE: I want to ask both of you, what are the dangers of that? We talked about earthquakes, Dennis cause more earthquakes? What does it mean when in California, we have groundwater basins that are a lot less than they used to be? RANDY HANSON: The big problem is, it starts to damage infrastructure. You look at the Delta canal California aqueduct, there's only about 40 to 50 feet of relief on the canal, over the whole length of hundreds of miles. It is not take much differential subsidence or total subsidence to ruin the integrity of the distribution of the surface water system. ADRIAN BORSA: I think we've all seen newspaper articles and see that there is a great economic and social impact, due to the drought. Not necessarily seismicity, but in other ways, there are certainly port in effects. TOM FUDGE: I guess we do not have a lot of groundwater in San Diego County, what is the situation locally? RANDY HANSON: Locally we rely on imported water, and our surface water reservoirs. We have a great deal for guaranteed supply from the Colorado River, but that is going dry, I'm not sure how that will play out, that is mainly where we get our water. TOM FUDGE: In San Diego county, are we locating new sources of groundwater? RANDY HANSON: We have study that we are doing in San Diego here, that is led by my colleague, looking at the groundwater resources to see where they are and how they could be cultivated. We want to diversify the portfolio, so to speak. TOM FUDGE: Will the study by Scripps help you? RANDY HANSON: I think so, looking at the water deficit and how other areas are responding, that might give us a better idea as to where the areas are most sensitive to recharge. TOM FUDGE: How can we limit the loss of groundwater? Is it simply by public policy, telling farmers that they cannot pump as much as they used to? Is that where we have to go? RANDY HANSON: We don't have any laws in place to govern that, like our neighboring states. This is an issue. It is not measured, either. We do not know how much they are taking, they have a right to take as much as they want from under the land. Most of that water is tens of thousands of years old. TOM FUDGE: Other states do this, we don't? We don't restrict the pumping of groundwater? What do you think of that, Adrian, is that a good idea? I know that restricting groundwater pumping would be controversial and politically difficult to do, but is that something we need to do? ADRIAN BORSA: I think we need to look long-term. One thing that the study offers is a tech Inc. that we can use going forward, even if we're not going to monitor individual farms, we can use a technique to ask the question of how different watersheds and basins are being used. It's a tool going forward. TOM FUDGE: Randy, how many years of decent rainfall are we going to have to have for the Sierra Nevada Mountains come down to the height where they should be? RANDY HANSON: We haven't looked at that, we took a look at a few scenarios and let that climate change and at radical drops in runoff, but recovery takes much longer to come back. We looked at the Valley behind Santa Barbara, and the weight use only replace, in those settings, a couple of years of pumping. It really takes a couple of wet years to recover an area like that. TOM FUDGE: Adrian, last word on you on that subject? ADRIAN BORSA: I don't have any word on that subject, but I do want to say that we can use the eight anywhere there is good GPS coverage, that means the continental US, Europe and Japan are covered, and the way that GPS networks are being built, pretty much anywhere around the world is open, looking forward. TOM FUDGE: Thank you both very much for coming in.

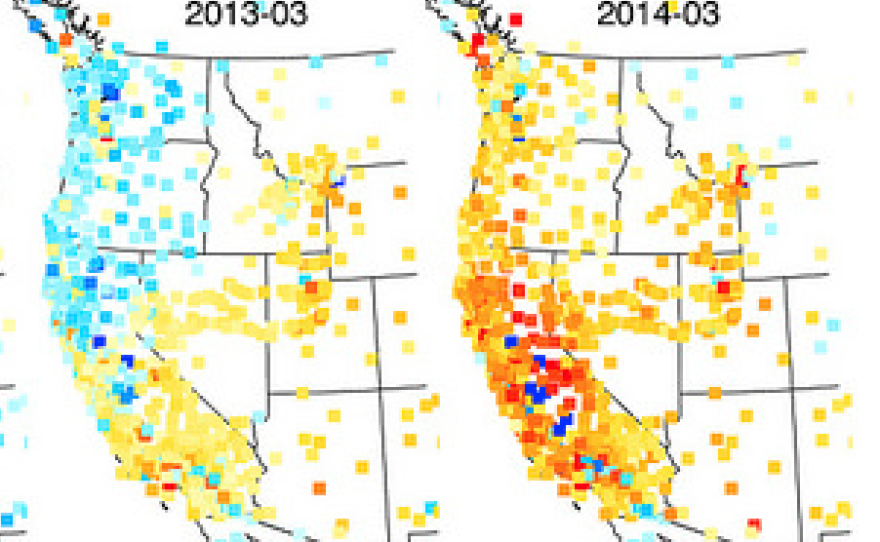

This weekend, Northern California was rattled by a 6.0-magnitude earthquake. That had nothing to do with the drought, right? Actually, a possible increase in seismic activity is one of the things that can result from the massive loss of groundwater we've seen since the western drought began.

The loss of an estimated 63 trillion gallons of water in West, most of it groundwater, was reported in a study done by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The loss of the water has caused the ground to actually rise more than a half-inch in California's mountains.