High on a West Bank hilltop, the extended Dissi family gathered on a recent weekend for a day out in the Palestinian countryside.

Aunts, uncles and cousins came to see the half-built weekend home of Taysier Dissi, an electrician and father of three. The concrete-block shell, with windows set and stairs roughed in, is placed just right for the view.

This will be the family's getaway from their home in the cramped confines of Jerusalem's often tense Old City. Dissi paid about $30,000 for one-third of an acre here, bought from a Palestinian-Canadian company, UCI.

"I wanted a change," he said. "I wanted to breathe fresh air."

UCI wanted him to have something else as well. In addition to the view and breathing room, the plot comes with benefits that aren't part of every real estate deal among Palestinians: surveyed borders and a title deed.

It's part of a project the company's general manager, Khaled Sawabi, calls a for-profit social enterprise designed to tackle several land problems at once.

"Land is unaffordable for Palestinians to buy within the cities," Sawabi says. "Outside the cities, land has no title deed, so you take a risk when you buy it. There is political risk. When Palestinian land doesn't have title deed, it's not protected from [Israeli] settlement expansion."

The land UCI buys from Palestinians to subdivide and resell often has never had a proper title. Certifying ownership and creating the documentation for deeds is part of the company's process.

"We do all the surveys, we draw the first borders, we go through the very long bureaucratic process of creating a title deed," Sabawi says. "Then we divide it up into small parcels to make it more affordable."

In much of the world, real estate wouldn't be bought or sold without a deed, which serves as proof of ownership. But the West Bank has a complicated history.

The Ottoman Empire began registering land to owners when it ruled here for four centuries, ending with World War I. The British Mandate government that followed continued land registration, including surveys. Jordan, which ruled what is now the West Bank between 1949 and 1967, started a systematic program of land registration, but didn't get very far.

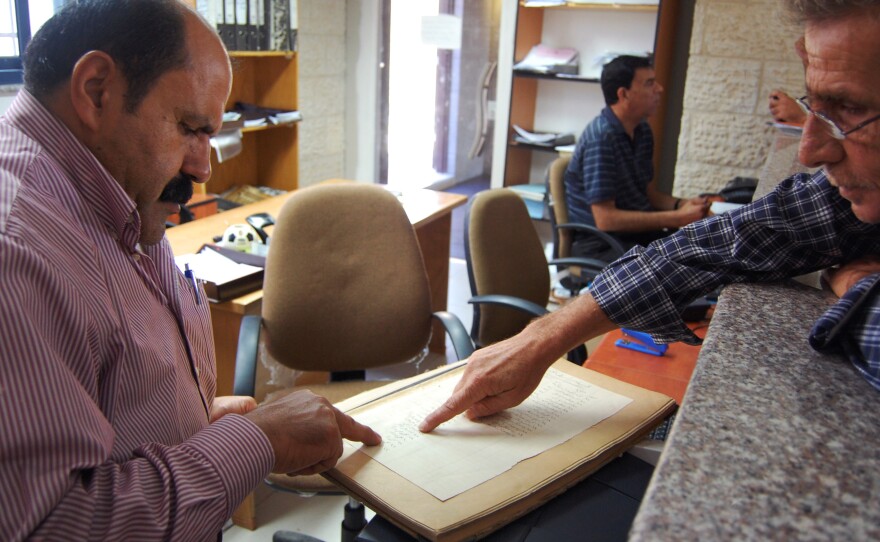

Large paper books from early eras are still used in determining ownership of land, although the handwritten entries are considered vague today.

After Israel captured the West Bank in the 1967 war, it sought to shift land to government control through a variety of methods.

The 1993 Oslo Accords, which were intended to be temporary, gave Israel the authority to administer land in more than 60 percent of the West Bank. Israel generally confines Palestinian development to the rest.

Nick Gardner, an adviser to the Quartet diplomatic group mediating the Mideast peace process, says the lack of clarity around land ownership across the West Bank discourages outside investment.

"If we could do one thing that would make a massive difference to the economic development of Palestine, it would be to sort out the land registration, effective land registration," he says.

The Palestinian Authority, also created by the Oslo process, can register land in the 40 percent of the West Bank it administers – the increasingly crowded cities, as well as smaller Palestinian towns and some undeveloped land.

But Sawabi contends the Palestinian administration hasn't done enough.

He's the first to admit it is difficult. Creating a title deed for land with none involves asking neighbors to agree on who owns what and can mean tracking down scores of heirs to family land, many who live around the world. Then there are GPS surveys, affidavits, and judges to sign off on it all.

Sawabi's flow chart of the process takes up three sheets of legal-sized paper.

The Palestinian Land Authority manages registration more on a case-by-case basis than tackling the problem systematically. The World Bank has invested in a broader approach, funding a Palestinian government effort to try to speed up registration of land.

But now halfway through, it met only one-third of the project goal, registering less than 7,000 of the 22,000 acres targeted. The bank is threatening to cancel funding, and encouraged the Palestinian Authority to spend the grant on a private contractor to give it a try.

Land Authority officials cite a variety of problems facing their registration efforts generally, ranging from Israeli military operations that can delay surveys to a lack of judges specializing in land issues.

UCI has feuded with the land agency and even sued over delays. It recently won a ruling that Sawabi says is now clearing a backlog of deeds that had not been issued on time.

Shawkat Barghouti, the land agency's director of registration, dismissed the lawsuit as a misunderstanding. But he personally doesn't like the UCI approach, buying land from Palestinian villagers, then re-selling the land with no housing on it, even before basic infrastructure is established.

"When someone buys huge amount of land like this, they should develop housing projects for people," Barghouti says. "They bought huge pieces of land, divided it, registered it, and sold it at higher prices with no investment."

Some Palestinians who sold land to UCI say they were initially skeptical of the company's intentions.

"We were afraid that these parcels of land, beautiful open parcels of land, were going to be sold to Jewish settlers eventually," says Jabar Arar in the village of Qarawat Bani Zeit, near several UCI developments. "We thought this was a front company that was buying up land with cash."

But he says their fears dissipated as they saw the project develop — and a few well-off villagers bought UCI plots, deeded after others sold.

UCI says the company invested plenty just to register the land. Although few owners have begun to build, blacktop roads are in most tracts. Electricity is on the way.

And since most plots are sold, the company believes it's meeting a need.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.