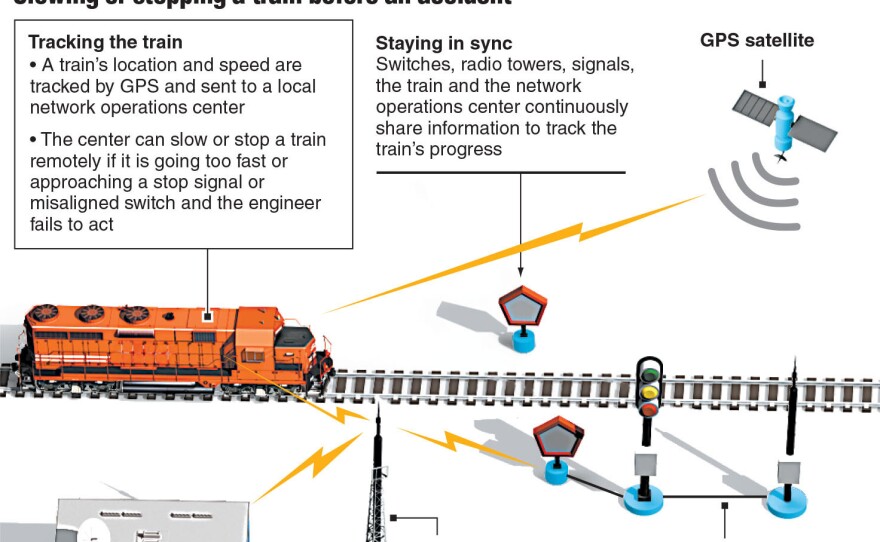

National Transportation Safety Board investigators say Positive Train Control — a system of satellites, communication towers and complex software that makes sure trains' safely follow their routes — would have prevented Tuesday's Amtrak train derailment in Philadelphia, which killed eight passengers.

Mandated by Congress after a head-on 2008 crash in Southern California killed 25, the system recognizes when signals turn red and where speed limits drop, and automatically will slow down or stop the train if the engineer misses a signal or goes over the speed limit.

The latter appears to have been a factor in the Philadelphia crash, in which the train was going over 100 mph as it went into a sharp curve with a 50 mph speed limit.

Amtrak CEO Joseph Boardman says the rail line is fully invested in meeting Congress' December 2016 deadline for the system, and even has it in place along portions of the Northeast Corridor — just not where this train crashed.

"We've spent $111 million getting ready for positive train control," he says. "We had to change a lot of things on the corridor to make it work, and we're very close to being able to cut it in."

The main holdup right now, he says, is radio interference. It's a problem that's bedeviled PTC from the start, says Karl Witbeck, an engineer who has worked on the system.

"Part of the challenge is that, in urban areas in particular, a lot of people are trying to access the spectrum," he says. "It's important to cell phone coverage, police and fire communications, stores even use it to track merchandise as it's scanned."

Anton Mittag, the director of engineering at NPR member station WNYC, uses a subway-train metaphor to explain why that's important.

"So we're seeing this train pull up right now and people are about to board," he says. "It's like spectrum in that each car is a band in the spectrum ... and you can put only so many people in each car and then it's full. You can't put in any more."

And no matter how badly you need to get on that train, Witbeck says, you can't just shove your way on board.

"You can't just take away spectrum that are being used by other people that already have a license," he says.

The obvious solution is getting railroads their own piece of the spectrum, Witbeck says, and the expectation was that the Federal Communictions Commission would allocate sufficient spectrum for the nation's railroads to use. But that didn't happen, and instead the railroads had to buy it on their own.

"You have these different federal agencies basically not working together and with Congress," Witbeck says.

By coincidence, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler was on Capital Hill just hours before the Amtrak derailment Tuesday, defending his agency's handling of Positive Train Control spectrum issues.

"For Amtrak, we've got new spectrum in the Northeast Corridor now, and we did some spectrum license transfers last week," he said.

Wheeler also says the agency has reduced lengthy delays in approving the thousands upon thousands of trackside radio antenna towers and poles that are needed for PTC.

He says the FCC is making "real, serious progress on PTC," but other officials say that, from the get-go, the FCC couldn't allocate spectrum to the railroads because Congress didn't authorize it.

Given that — and given the host of other complex, technological hurdles the industry has encountered in implementing PTC — railroad industry consultant Charlie Banks says Congress should have put more thought into whether Dec. 31 was a realistic deadline.

Amtrak says it will be done setting the system up in the Northeast Corridor by then, but very few other railroads will meet that timeline — and some say it may take at least five more years to fully implement Positive Train Control.

Karen Rouse is a reporter for member station WNYC in New York.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.