First in a three-part report on solitary confinement use in U.S. prisons.

In the yard at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, gray-haired men make their way up to a small stage. A towering stone prison wall rises overhead. One by one they sit at a scratchy microphone and tell their stories — of being locked up 23 hours a day in a place that just about broke them.

"This place here really did something to me psychologically," says former inmate Anthony Goodman.

Eastern State is the prison where solitary confinement was pioneered in the U.S. It's a museum now, but the reunion here is a chance for former inmates to talk about what it meant to do time here.

"Because this place would make you go insane if you didn't know how to handle it," Goodman says.

Fred Kellner was a psychiatrist charged with looking after inmates' mental health. He says he knew conditions at Eastern State were hurting people, but he felt powerless.

"I remember being bothered by various situations. You can't do much about it because the most important thing in a prison is control. And that rules," he says. "If you expect to change it, you're in for depression."

Here's one of the first things you learn when you study the history of solitary confinement: People have had deep doubts about isolating inmates for a really long time.

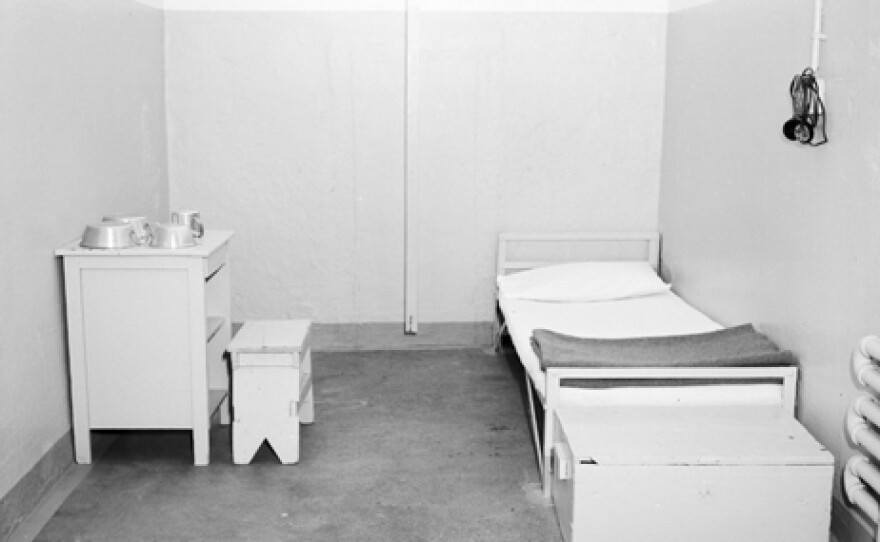

The earliest experiments were carried out here at Eastern State in the 1800s in tiny, monastic cells. Sean Kelley, director of education at Eastern State, says at first people really believed that isolating criminals for long periods might help them heal, make them more virtuous.

Critics didn't buy it. The British author and activist Charles Dickens who visited in the 1840s described long-term isolation as "ghastly," a form of "torture." Kelley says the people running Eastern State didn't listen. Decade after decade they kept trying to make the system work.

"The officers and the administrators would write about the inmates becoming agitated. They would have to carry out really extreme physical punishments to maintain silence. They would literally put them in strait jackets and douse them in water in the wintertime and leave them outdoors," he says.

'It Has All Come Back Around'

Stories like that led to solitary confinement being widely discredited here in the U.S. and around the world. Beginning in the early 1900s, long-term isolation was used rarely with the most dangerous inmates and usually for only short periods, a week or two. But Kelley says the idea had woven itself deep in the DNA of American prisons.

"It is shocking to see that we've gone back to it. There are tens of thousands — they say 80,000 people on given day — living in solitary confinement in the United States. We're used to seeing this as being a historical practice, but it has all come back around," he says.

The big revival came in the 1980s and 1990s. The drug war sent a tidal wave of inmates surging into state and federal correctional facilities. There were riots, gang violence and assaults on guards.

Prison officials looking for a quick fix so started building new isolation wards in prisons, and they also designed an entirely new kind of prison known as a Supermax correctional facility.

These are separate prisons that function very much like Eastern State Penitentiary did in the 1800s, locking inmates in cells for 23 hours a day with little interaction with guards or other prisoners. Nazgol Ghandnoosh of The Sentencing Project says solitary confinement is now hardwired into the architecture of America's prisons.

"Right now there are are at least 20 Supermax prisons, and they hold 20,000 people," Ghandnoosh says. "[At] one of the prisons in California, Pelican Bay, for example, half of the prison population, 500 people, have been there for more than 10 years."

Some inmates have been confined in solitary for 20, 30, even 40 years at a time. The practice is now such a standard disciplinary tool in the U.S. that even nonviolent inmates are often placed in isolation for months or years at a time.

"I think it's very important for prison authorities and the public to reflect on whether it's humane to subject people to this form of isolation that play havoc with people's sanity," Ghandnoosh says.

Juan Mendez is a special investigator on human rights with the United Nations. He's worked extensively on the issue of America's system of solitary confinement.

It's common, Mendez says, for prisons in the U.S. to hold young people, inmates with mental illness and pregnant mothers in long-term isolation.

"The psychiatric and medical literature is very clear. Deprivation of meaningful social contact does create pain and suffering," Mendez says.

Studies show that solitary confinement can lead to higher rates of suicide and other forms of mental illness, even in modern prisons where inmates in segregation cells are sometimes allowed radios or televisions. Those findings have led top prison administrators like Greg Marcantel in New Mexico to look for new ways to scale it back.

"It's very, very easy to overuse segregation. I mean, for a guy like me, it's safe, right? It's safe. If these prisons are quiet, I don't get fired," he says.

In all, a dozen states are looking to reform the way they use solitary confinement. But here's a sign of how hard it might be to shift away from long-term isolation in American prisons: As President Obama condemned the use solitary confinement last month, his administration is finishing construction of a new $200 million Supermax correctional facility in Illinois. Its hundreds of isolation cells are expected to begin holding inmates next year.

Copyright 2015 North Country Public Radio. To see more, visit http://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/.