It's getting harder and harder to find quality special education teachers, which is why 49 out of 50 states report shortages.

Why? It's a tough sell.

Even if you're up for the low pay and noisy classrooms, special education adds another challenge: crushing paperwork.

This is something I understand first hand. You see, I was a special education teacher and I just couldn't hack it. Though I'm somewhat ashamed to admit it, I only lasted a year in the classroom.

I chose special education for what felt like the right reason. I wanted to help the students who struggle to learn. But I soon realized that was only a part of the job.

The paperwork, the meetings, the accountability. Eventually it got to me. I couldn't do it all and I got tired of showing up to a job I knew I couldn't do. It's that simple.

So, as I've been looking into the teacher shortage it hasn't felt like a revelation that people are leaving the profession. I get it.

But I have been curious about my friends and colleagues who have stayed. Especially one colleague in particular: Stephanie Johnson.

I know Stephanie from my college days. We were in the same special education program at Brigham Young University three years ago. But as a mother of three returning to school in her 40s, Stephanie wasn't your typical student.

She's now going on her third year teaching eighth grade math and ninth grade English to students with a wide range of disabilities at Oak Canyon Junior High School in Lindon, Utah, which is about 40 miles south of Salt Lake City.

'My Joy Is In The Classroom'

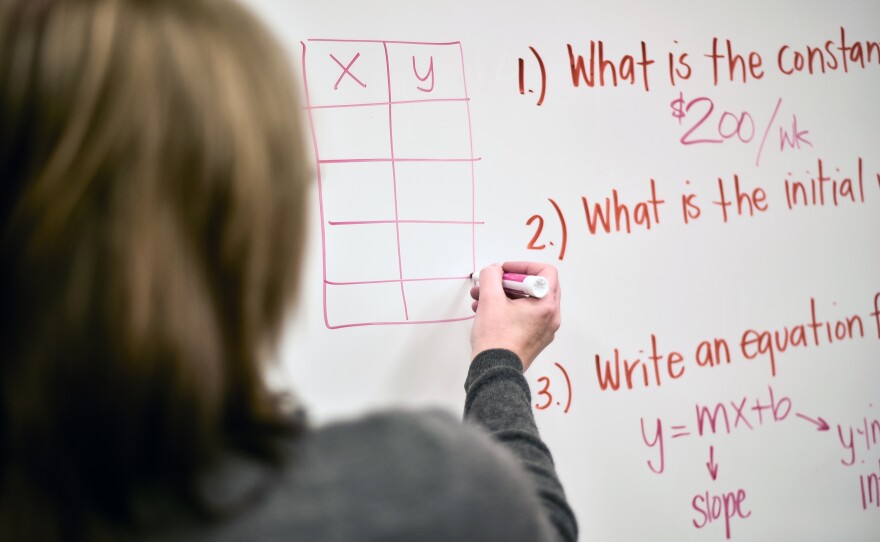

I visited Stephanie's classroom during a math lesson. She was reviewing how to find the slope of a line, through word problems. You know, x-axis y-axis type stuff. The students copied some problems from the board and got to work.

The class was surprisingly quiet and focused. If I had been teaching I might have leaned back, put my feet up on the desk and enjoyed the moment.

But not Stephanie.

She weaved through the desks, kneeling beside each student and checking in. I could tell she was in her element.

I checked in with a few students too. Each one had the same responses to my questions.

Do you like math?

No.

Are you good at it?

No.

How are you doing in Mrs. Johnson's class?

Good. It makes sense when she explains it.

"My joy is in the classroom," Stephanie told me afterwards. "When they catch onto something and they have those 'a-ha' moments."

Those "a-ha" moments are no small feat. Each of Stephanie's students has some type of learning disability. Many have become accustomed to the feeling of being totally lost during their classes, especially math.

But there they were, scribbling away with that scrunched concentration on their faces. None of them looked lost.

This didn't surprise me. Back in college it was obvious that Stephanie would be a dynamic teacher.

For starters, she understood special education from a parent's perspective. One of her sons, Alec, was in special education classes from second through ninth grade. She knows the heartache and worry that comes when a parent is told their child learns differently.

"Now as the teacher I can say, 'I know exactly how you feel, I've been there and it's going to be OK,' " Stephanie says.

She was also a teaching assistant in a special education classroom at a middle school for five years. And on top of that she was an extremely driven student.

Because of all this, my classmates and I looked up to her. She was a kind of mentor to us. She helped us see the purpose in what we were preparing to do.

"I was really clear on why I was there," Stephanie remembers.

She pauses. "I wish that was more clear now."

Not Enough Hours In The Week

From the outside, it looks like Stephanie has everything under control. But that's now how she feels.

"I don't know how to describe it," she says. "It's just so much work."

She's not talking about teaching or lesson planning or even working with disruptive students. She really likes those parts of the job.

"It's all the other compliance and laws and paperwork."

All of that stuff can be summed up with three letters: IEP. That stands for Individualized Education Program. Each student in special education has one. It's required by law. And each IEP requires hours and hours of upkeep.

Forms need to be updated, data has to be tracked and there are additional meetings with parents and other staff. Multiply that by the 43 students Stephanie has, and there goes all of her free time.

"I stay at work hours typically every day," Stephanie said. What she doesn't finish, she takes home.

In 2011, Donald Deshler, a professor of special education at the University of Kansas set out to examine just how many hours all that paperwork consumes. He and a doctoral student wanted to find out what the typical special education teacher's workload looked like.

They decided to observe a few teachers during their workday. "We followed them everywhere, except the bathroom," Deshler says.

They then broke down the teacher's typical work day into four main categories with the percentage of time spent on each:

- Management, IEP paperwork and administrative responsibilities: 33 percent.

- Collaboration, co-teaching, assisting other teachers and meetings: 27 percent.

- Instruction, teaching students in their classroom: 27 percent.

- Diagnostic, testing and data tracking: 13 percent.

Of the 27 percent time spent teaching, only 21 percent was what Deshler considered "specialized instruction," meaning the teachers were using methods that were evidence-based and focused on students' individual needs.

"Twenty-one percent of their time is spent teaching the best of what we know. That roughly translates into one day a week," Deshler explains. "If we wonder why teachers are frustrated, this data sheds some light on it."

And that frustration leads good teachers like Stephanie to question whether or not they can stay in the profession. She admits she thinks about leaving all the time.

"Just because I'm exhausted," she says. "But I'm changing kids lives, I'm making a difference, so why would I want to walk away from that?"

So, when it comes down to staying or leaving Stephanie feels stuck. It's an extremely difficult decision for an extremely difficult job.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.