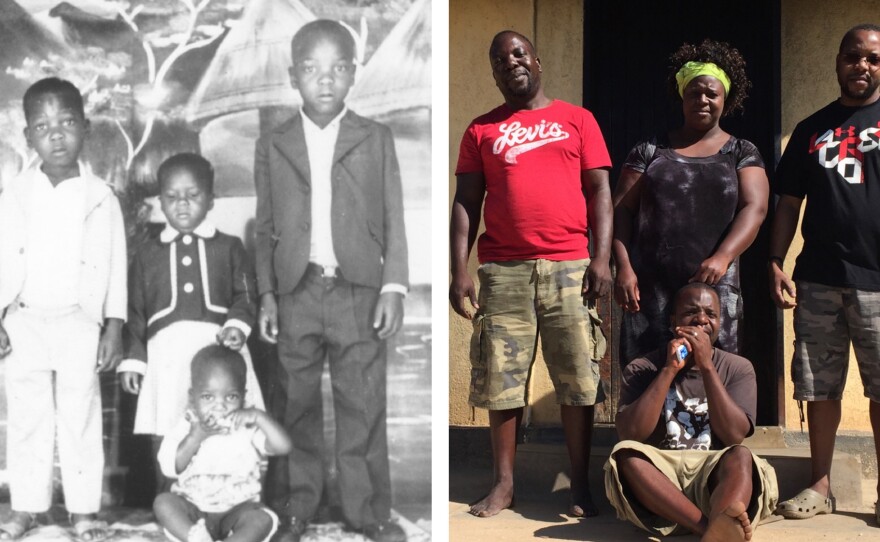

Last Christmas, my daughter, Iza, and I woke up to many presents under the Christmas tree. As we enjoyed our breakfast of omelets, sausages, cheese, fresh bread and fruit salad, I thought back to my childhood Christmases. I grew up as the sixth of 10 children in a village in rural Zimbabwe. We didn't have much, but I didn't feel that I was poor. My childhood story is still typical of many rural kids living in developing countries.

I have vivid memories of the festive season in the village, where everyone observed Christmas. By early December, all the kids were counting down the days until the holiday. A few days before the big day, family members who had left the village for the city would start to trickle back into the village, bringing urban goodies (fresh bread, sticky buns, sausages, soda, cookies and condensed milk), wearing fancy clothes — and shoes (we village folks only wore shoes to go to church on Sundays).

At Matimati's — the tiny village grocery store that smelled of kerosene — adults would gather around a battery-powered vinyl record player listening to the latest hit songs. Men would drink lots of beer — Castle Lager, Cola Cane, Don Juan and Chibuku.

When the big day finally arrived, my siblings and I woke up early to do our morning chores: sweeping the yard and feeding the animals. Then we'd go down to the river for a bath. By 9 a.m. we were ready to go to the Grade 2 classroom at the primary school where church services were held, sporting our "Sunday best" outfits with shoes that were often too big or too tight. After a one-hour service with spirited singing and a sermon about the birth of Jesus, we ran back home to celebrate Christmas.

We did not get new toys or clothes, nor did we expect them. What made Christmas special was the food. Yes, the food. For our late morning breakfast, we would have lots of white bread with a generous spread of Sun Jam, a very sweet and bright red canned plum jam. We washed this down with Tanganda, a black tea produced in Zimbabwe, that was mixed with lots of condensed milk — a major upgrade from the plain black tea we typically drank for breakfast.

After breakfast, we went out and played soccer, hopscotch and jump rope with our neighbors, often exchanging stories about the special foods we had eaten for breakfast. Later, our oldest sibling would take whatever change my mother could spare, check his pocket for holes, then put the money in the pocket. We'd run to the village store, where we took our time choosing from the three types of candy. First was the Goromonzi, a big yellowish, peach-flavored and peach-shaped sucking candy that cost 5 cents each and could fill your whole mouth. Second was the Crystal, a smaller mint-flavored sucking candy that was wrapped in clear plastic and sold for 2 cents a piece. Last and certainly least expensive were the small nickel-sized balls of hard candy brightly colored in red, green, or yellow. You could not beat them on value — very sweet, long lasting and cheap. Also, the bright colors lasted for hours on your tongue and lips, which served as good evidence to show off to your less fortunate friends.

Dinner was the best part of Christmas. We gorged ourselves on rice and chicken or goat stew. Our otherwise dull and ashy hands would glisten from fat and oil. We could ask for seconds or even thirds. After dinner, my brothers and sisters would sing the Christmas hymns loudly before nighttime prayers. We prayed for good rains, better health for anyone who was ill and blessings to family members who could not join us that year. As we went to bed with bellies stuffed with food, we would start the countdown till next Christmas. Just 365 days to go!

As I watch my daughter open presents this Christmas, I'll be grateful that eating until she's full isn't the best part of her holiday. I'm happy that she can help herself to seconds any night of the year if she wants. And while my family in Zimbabwe didn't go hungry, many in our village were not as fortunate. As we celebrate the festive season this year, please spare a thought, or better yet a gift, for the 795 million people who go to bed hungry every night.

Edward Mabaya is an agricultural economist and associate director of the Cornell International Institute for Food, Agriculture & Development. He is a 2016 Aspen Institute New Voices Fellow. Follow him on Twitter at @edmabaya.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.