This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

Gov. Gavin Newsom two years ago launched a new program called CARE Court that gave hope to families struggling with severe mental illness.

It promised to provide treatment and housing through court-supervised plans that would keep difficult-to-help individuals on track.

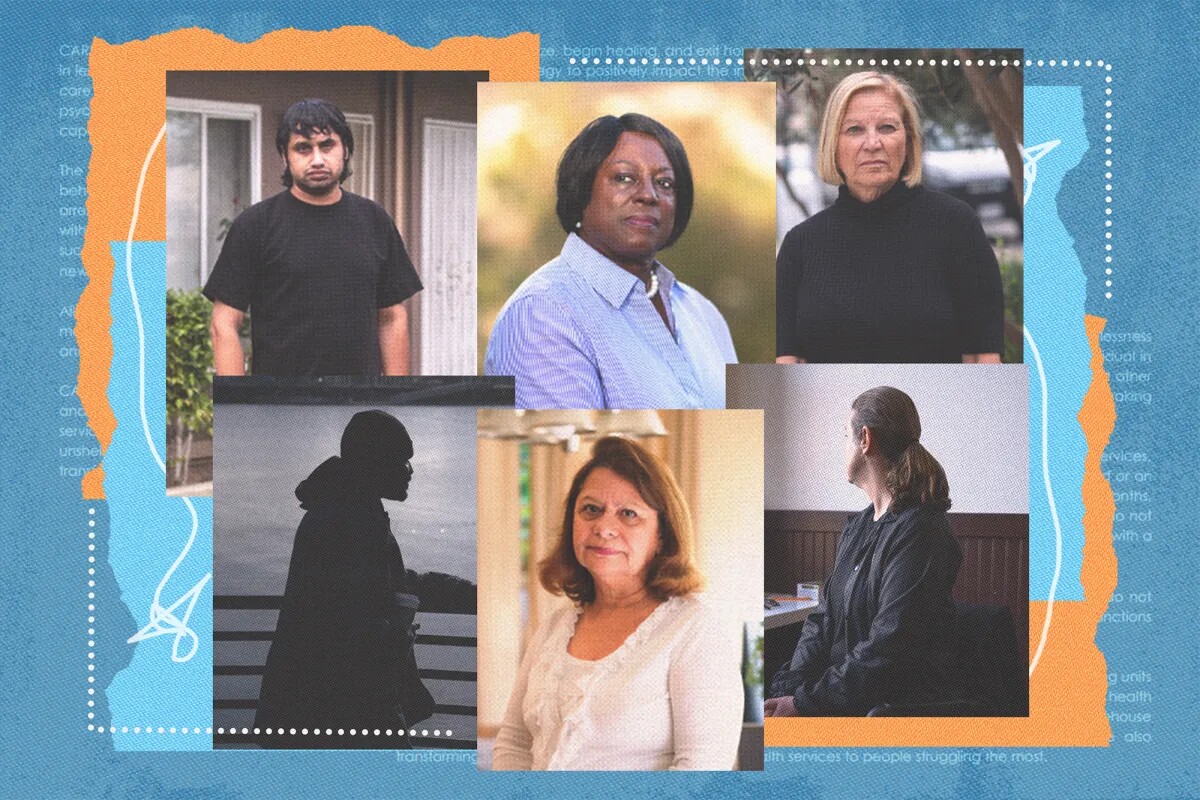

We spent much of the past year talking with dozens of people who’ve interacted with CARE Court as participants, petitioners and as employees trying to fulfill the program’s goals.

Here’s a sampling of their experiences.

'I felt so defeated'

Last summer, June Dudas was in church when she got a text message from her 84-year-old aunt: “He’s here.”

Dudas called back, and, in a whisper, her aunt said she’d locked herself in the bathroom to hide from her son, Ed, who was outside her San Diego home. It was an all-too familiar situation. Over the years, Dudas had helped her aunt fortify her fence, install multiple security cameras and file restraining orders. It was an effort to protect her from a man who, when not gripped by psychosis, was a “gentle giant” who loved animals and made jewelry out of gemstones – but, when at the mercy of his delusions, could turn violent.

This time, Dudas told her aunt, she had a new solution. She had just learned about CARE Court, which she’d heard could compel people into treatment. Dudas’ aunt quickly submitted a CARE Court petition on her son’s behalf.

But when the CARE Court team offered Ed help, he refused, according to Dudas. Saying there was nothing more they could do, a judge dismissed his case.

“I felt so defeated for my cousin,” Dudas said. “It’s like, ‘OK, Eddy, they’re saying that when you’re well enough to understand how sick you are, then they’re ready to help you, but until then you’re on your own, buddy, and there’s nothing they’re going to do for you.’ And it just struck me as very callous.”

Dudas’ aunt tried again with a second petition in October. That one was dismissed as well.

Now, Ed is in jail for violating his mother’s restraining order. Dudas worries that when he gets out, which likely will be early next year, her family will be back where they started: With her and her aunt living in fear, and Ed still not getting the help he needs.

'Life's treating me pretty good'

When outreach workers found J.M. in February, he was sleeping on some blankets under an awning in Oakland. He didn’t have a tent, despite the winter cold, and he couldn’t walk due to a foot injury. He wore multiple pairs of pants and socks in an effort to compress his foot and relieve the pain and swelling.

J.M., who had been homeless for several years, asked CalMatters to refer to him using his initials, to protect his privacy.

At first, the county sent J.M. to a psychiatric hospital on a temporary hold. He received treatment for his foot and for his mental health, but said it was frustrating to have no choice in the matter. He found the facility depressing and didn’t like the food.

When he was discharged, CARE Court got him a room in a hotel in downtown Oakland that was converted into temporary housing for clients who need mental health services.

Now, J.M. regularly walks the half mile from the hotel to the waterfront at Jack London Square, where he sits and watches the water.

He wants to go back to school and get his GED diploma. He dropped out of high school in ninth grade, and he’d like to find a tutor to help him with his reading, spelling and vocabulary – areas he’s always struggled with. He’s looking for work, and trying to quit smoking cigarettes.

"It's been pretty good,” J.M. said. “Life's treating me pretty good."

'They were so caring'

CARE Court has been a lifeline for 64-year-old Mary Peters of Riverside. Until then, Peters was navigating her younger sister’s mental illness all on her own.

In addition to her sister, Peters was helping to take care of their father, who had dementia. Meanwhile, her sister bounced in and out of the hospital and homelessness. Sometimes, Peters didn’t know where she was or how to find her. Even if she suspected her sister was hospitalized, hospital staff often wouldn’t give her any information, citing patient privacy.

Peters filed a CARE Court petition on her sister’s behalf in October 2023, and all of that changed. Suddenly, she had people to help her. The CARE Court team tracked down her sister when Peters’ couldn’t, and got her into a sober living facility. When her sister didn’t like that facility, they helped her move somewhere else, Peters said.

“Without the CARE team, it would have been impossible for me to do this,” Peters said. “There were times when I wanted to give up. There were days when you just kind of throw your hands up, if someone is feeling so hopeless and you’re doing everything you can to try to help.”

Peters’ sister graduated from CARE Court earlier this year, in a small courtroom celebration with cupcakes. Now, she lives in her own apartment in Riverside.

Her sister still has her ups and downs, but she seems more clearheaded now, she reconnected with her two adult sons, and she feels less hopeless, Peters said. And she credits CARE Court.

“They were so patient,” Peters said. “They were so caring.”

'My sister that I used to know ...'

Antonio Hernandez first learned about CARE Court when he saw a flyer that his older sister brought home after being discharged from a treatment facility.

“I was so excited about this CARE Court,” he said. “Oh my gosh, that’s exactly what we need.”

His sister, who has schizophrenia, was stable then, taking medication and talking about getting a job.

Hernandez filed a petition for his sister to enter CARE Court in Kern County. The county’s CARE Court process was rife with delays and extensions, her brother said. In the meantime, he said, his sister was left in limbo and began decompensating.

Eventually, she was evicted from a Bakersfield room and board and transferred to a sober living home, he said. Six months after he first petitioned, he said, his sister signed the CARE agreement. That same day, she was kicked out of the sober living facility, too.

She became homeless, camping in the park and talking to herself, he said. She stopped taking her medication.

“You have to be at your worst for them to help,” he said. “It kind of makes no sense. They expect you to be at your worst to be accepted. At the same time, they expect autonomy from patients to make their own decisions when they’re at their worst.”

He worries about the irreversible damage being done to his sister’s brain.

“My sister that I used to know, I’ll no longer get to have that sister anymore because of their failure, their negligence, and their inability to follow through with what the law states,” he said.

A life-changing program

C.M., 55, was on the verge of homelessness when CARE Court stepped in last January.

In her 40s, she’d started experiencing bouts of psychosis when she was under extreme stress, with terrifying symptoms that included hearing cruel voices or feeling like her body was being shocked with electricity.

In her 50s, she lost her construction management job because of one of those episodes, and struggled to pay the rent on her San Leandro apartment. Her disability benefits were about $1,600 a month, but her rent was $1,750. She drove for Lyft to try to close the gap, but then her Lyft app started glitching, she said. She knew she couldn't pay her bills, and the stress sent her spiralling into another episode of psychosis.

In January 2025, one of the EMTs on San Leandro’s mental health crisis response team saw that she needed help, and filed a CARE Court petition on her behalf.

Now, C.M. has her own room on the first floor of an old Victorian house in West Oakland, with a window overlooking a yard and a giant agave plant. She’s taped photos of her two adult sons as little boys to one of the walls, next to a printed-out list titled “coping skills.”

“I literally didn’t spend any time on the streets after I got evicted, because of CARE Court,” said C.M., who asked to be referred to by her initials out of fear that being associated with schizophrenia would hurt her chances of getting a job.

She can live there rent-free while her caseworkers help her find permanent housing. That stability is important for anyone, but it’s particularly life-changing for C.M., as financial stress and the fear of homelessness are psychological triggers that can launch her back into psychosis.

Now, C.M. is looking toward the future. She’s starting school for construction management next year, and hopes to find another job in the industry. But there’s some uncertainty there as well. C.M. is set to graduate from CARE Court in April, and as that date fast approaches, she’s still not sure where her next housing placement will be.

'This is what families have to endure'

At first, Anita Fisher was an enthusiastic advocate for CARE Court. She met with Gov. Newsom to discuss it. She appeared on 60 Minutes talking about how the program was a promising tool to help people with serious mental illness.

At the time, her own son, who is diagnosed with schizophrenia, was doing well.

Some of her last words in the 60 Minutes interview?

“I hope he will never have to use it.”

Then her son stopped his medication and ended up in a mental health crisis.

Fisher’s petition for CARE Court in San Diego County was accepted. But, soon, her son was arrested. Then he was discharged to the streets. At one point, he went missing.

“Can you imagine having to wonder if your son is alive or dead for three weeks?” she said. “This is what families have to endure.”

Her son, who she describes as a sweet, docile man, had been an Army medic with an impeccable record until his illness popped up at the age of 21. Now he kept going to jail.

Two years after she first petitioned CARE Court to get him help, she has nothing positive to say about the program she once lauded.

“I look at it as a total failure,” she said.

This story was produced jointly by CalMatters & CatchLight as part of our mental health initiative. It was reported with support from the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.